Why some kids struggle with math even when they try hard

Researchers at Stanford University led by Hyesang Chang set out to better understand why some children find math much

Researchers at Stanford University led by Hyesang Chang set out to better understand why some children find math much harder than their classmates. Their findings were published in the journal JNeurosci, a peer reviewed neuroscience journal that focuses on how the brain supports thinking and behavior.

Many people assume math difficulties are simply about not understanding numbers. However, this study looked deeper at how children think, learn from mistakes, and adjust their strategies over time.

Testing Number Comparison Skills

In the study, children were asked to complete a series of simple comparison tasks. On each trial, they had to decide which of two quantities was larger. Sometimes the quantities were shown as written numbers such as 4 and 7. Other times, the quantities were displayed as groups of dots, requiring the child to quickly estimate which group contained more items.

By switching between number symbols and dot clusters, the researchers could test both symbolic number understanding and more basic quantity recognition. Instead of focusing only on whether answers were right or wrong, the team developed a mathematical model to track how each child’s performance changed across many trials. In other words, they examined how consistently children performed and whether they adjusted their approach after making mistakes.

Difficulty Updating Thinking After Mistakes

The results showed a clear pattern. Children who struggled with math were less likely to change their strategy after getting a problem wrong. Even when they made different kinds of errors, they did not seem to update their thinking in response. This difficulty in adjusting behavior over time was a key difference between children with typical math abilities and those with math learning challenges.

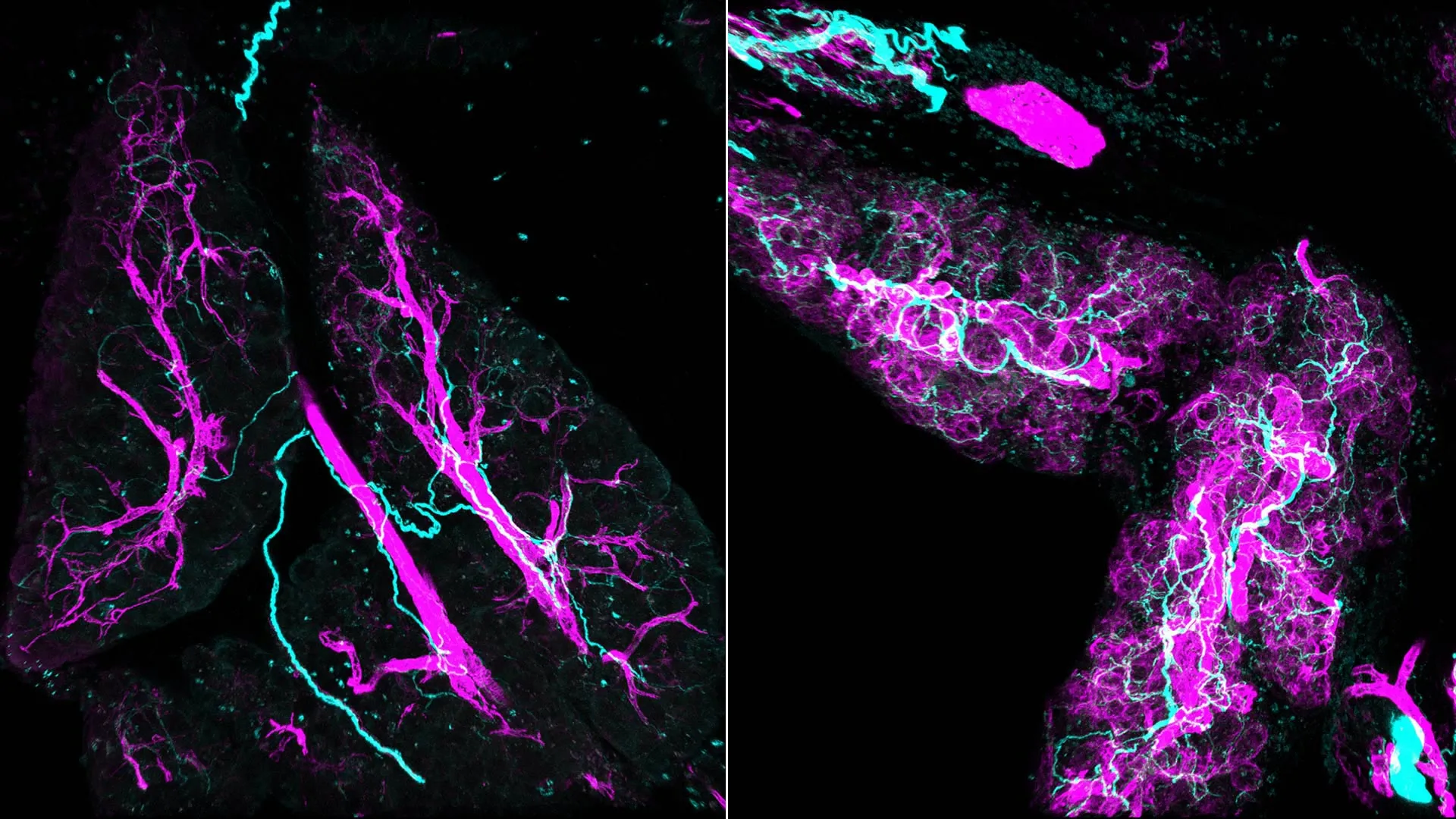

To better understand what was happening in the brain, the researchers used brain imaging. This technique measures activity in different regions of the brain while a person performs tasks. The scans revealed that children who had more trouble with math showed weaker activity in areas involved in monitoring performance and adjusting behavior. These brain regions are often linked to cognitive control, which refers to the ability to evaluate mistakes, shift strategies, and adapt to new information.

Importantly, lower activity in these regions could predict whether a child had typical or atypical math abilities. This suggests that differences in brain function may help explain why some children consistently struggle.

Math Struggles May Reflect Broader Cognitive Challenges

The findings indicate that math difficulties may not stem only from problems with understanding numbers. Instead, some children may have trouble revising their thought processes as they work through problems. Being able to recognize an error and try a new approach is essential not just in math, but in many types of learning.

Chang emphasized this broader implication, stating, “These impairments may not necessarily be specific to numerical skills, and could apply to broader cognitive abilities that involve monitoring task performance and adapting behavior as children learn.”

The researchers plan to test their model in larger and more diverse groups of children, including those with other types of learning disabilities. By doing so, they hope to determine whether challenges with adapting strategies play a wider role in academic struggles beyond math.