Why it’s easy to be misunderstood when talking about probability

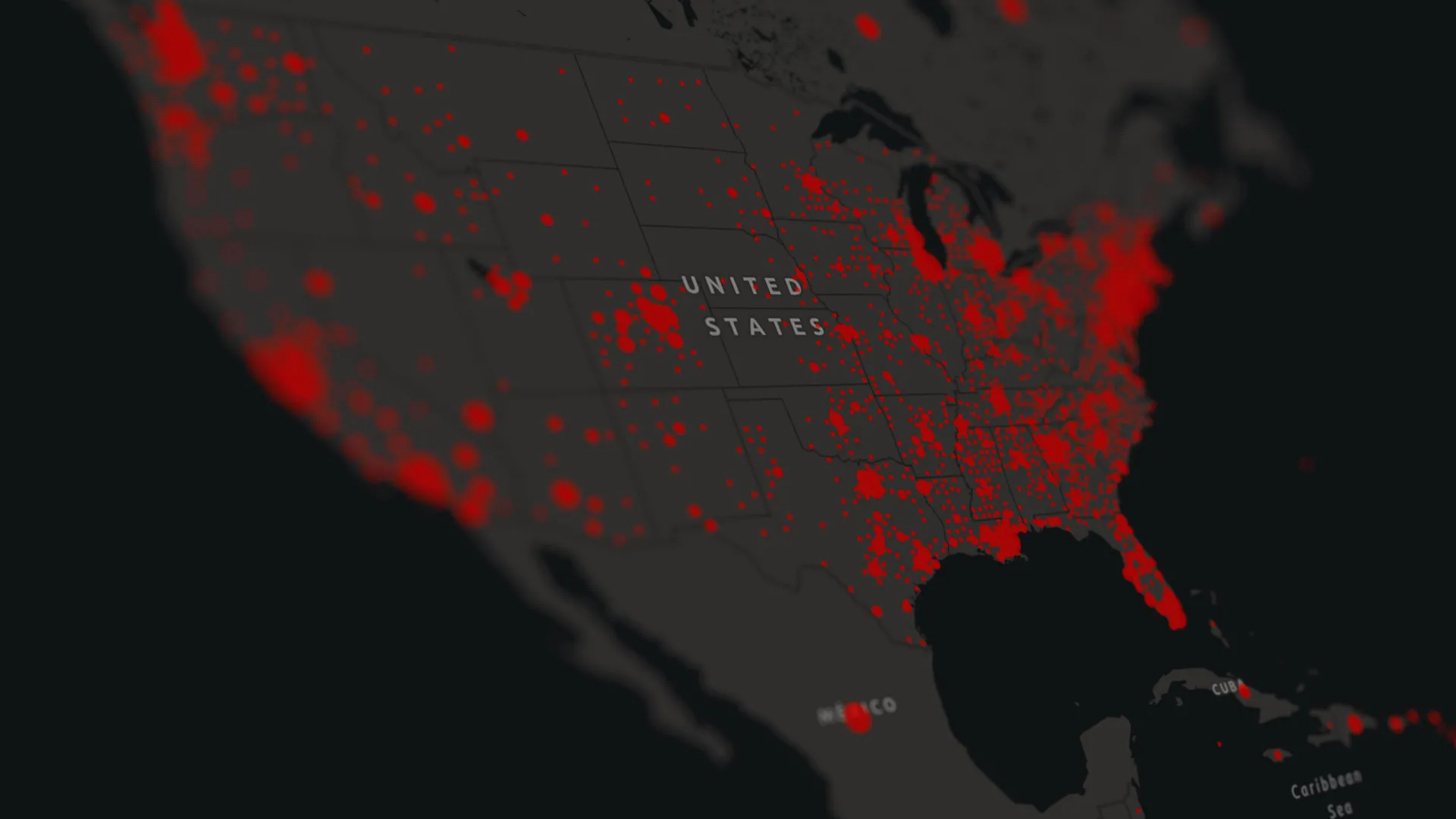

The words we have for probability make it hard to say what we mean Makhbubakhon Ismatova/Getty Images If someone

The words we have for probability make it hard to say what we mean

Makhbubakhon Ismatova/Getty Images

If someone told you that they were “probably” going to have pasta for dinner, but you later found out that they ate pizza, would you feel surprised – or even lied to? More seriously, what does it mean to be told that it is “very likely” that Earth will exceed 1.5°C of warming within the next decade, as the United Nations reported last year? Translating between the vagaries of language and the specifics of mathematical probability can be tricky, but it turns out it can be more scientific than you might think – even if it took us quite a long time to arrive at a translation.

There are two words that most of us can agree on when it comes to probability. If something is “impossible”, its chance of occurring is 0 per cent, while a “certain” event has a 100 per cent chance of coming to pass. In between, it gets murky. Ancient Greeks like Aristotle distinguished between eikos, that which is likely, and pithanon, meaning plausible or persuasive. Already, we are in trouble – in the right rhetorical hands, something that is persuasive doesn’t necessarily have to have a high probability of being true. To make matters worse, eikos and pithanon were sometimes used interchangeably, leading the ancient Roman orator Cicero to translate them both as probabile, the root of our modern word probability.

The idea of a measurable, mathematical approach to probability didn’t emerge until much, much later. It was first developed in the mid-17th century during the Enlightenment, by mathematicians who wanted to solve various problems in gambling, such as how to fairly divide the winnings if a game is interrupted. Around the same time, philosophers began asking whether it was possible to quantify different levels of belief.

For example, in 1690, John Locke labelled degrees of probability by their strength on a spectrum, from assurance or “the general consent of all men, in all ages, as far as it can be known”, through confidence in our own experience, to testimony, which is weakened by being repeated second- or third-hand – an important legal principle both today and at the time he was writing.

This link between the law and probability remained an important one for philosophers. Writing in the mid-19th century, Jeremy Bentham noted that when it comes to quantifying the strength of evidence provided by a witness, “the language current among the body of the people is, in this particular, most deplorably defective”. He wondered whether words can reflect certainty “in the same way as degrees of probability are expressed by mathematicians”. Bentham suggested asking people to rank the strength of their belief, positive or negative, on a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 corresponded to no degree of persuasion. Ultimately, he concluded the idea has merit, but its subjectivity and variation from person to person would make such a scale of justice impractical.

A century later, the economist John Maynard Keynes was scornful of Bentham’s proposed scale of certainty, favouring a more relational approach to probability. Rather than focusing on hard numbers, he thought it made more sense to talk of one thing being more or less probable than another. “We may fix our attention on our own knowledge and, treating this as our origin, consider the probabilities of all other suppositions,” he wrote. Here, we have a hierarchy, but not a systematic way of conveying the specific meaning of “probable” or “likely” from one person to another.

Perhaps surprisingly, it wasn’t a mathematician or philosopher who first truly cracked this problem – it was an intelligence analyst for the CIA. In 1964, Sherman Kent wrote a confidential (but now declassified) memo titled “Words of Estimative Probability”. His particular concern was the preparation of National Intelligence Estimates, a series of classified documents used to inform policymakers. For example, if an analyst writes that a spy satellite photo “almost certainly” shows a military airfield, what conclusions should the US president draw?

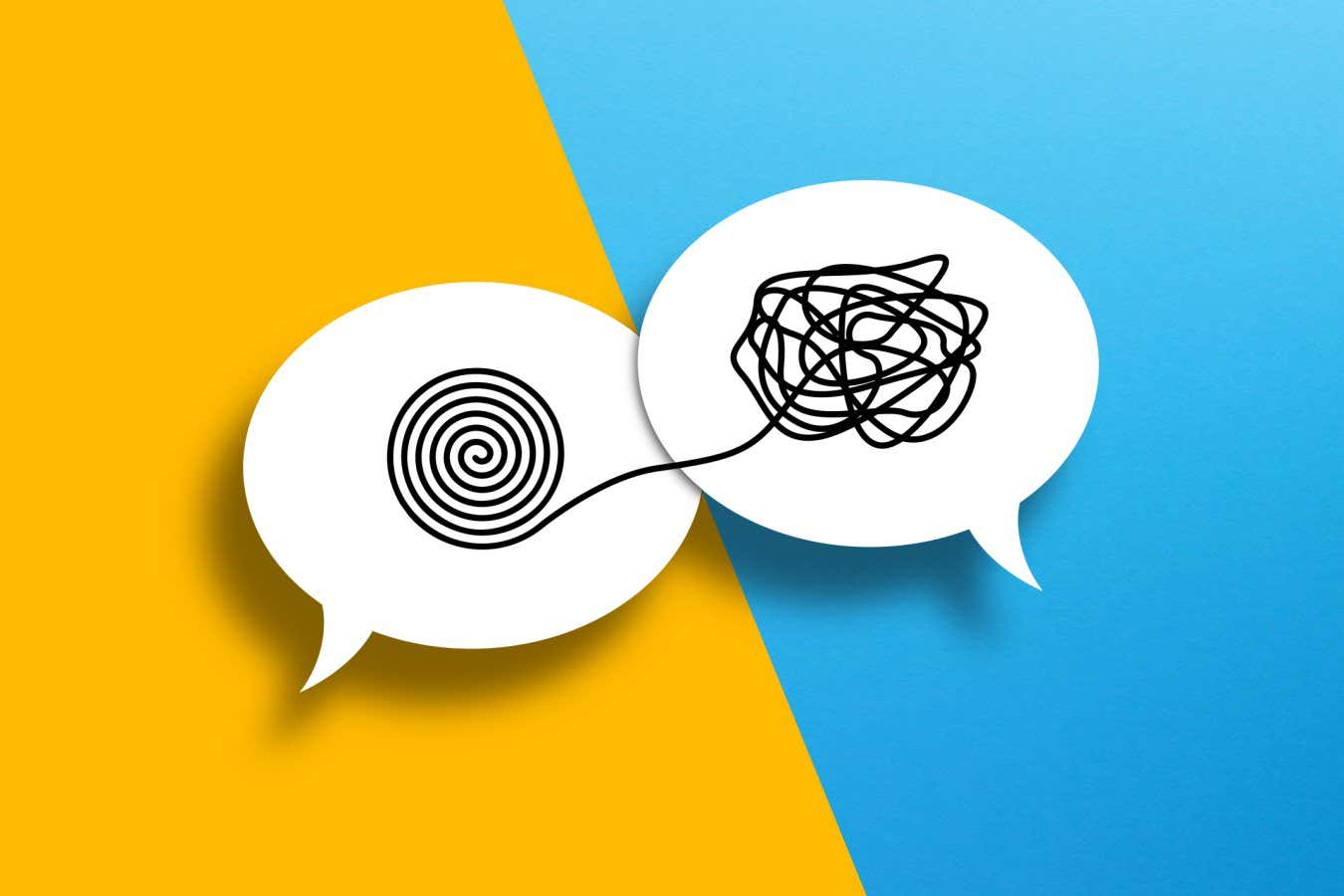

Kent laid out the now familiar clash between what he called the “poets” – those who attempt to convey meaning by words – and the “mathematicians” who favour hard numbers. In an effort to find peace between the two camps, he proposed that specific words should be understood within the intelligence community to mean specific probabilities, so that, for example, “almost certain” be taken to mean a 93 per cent probability of being true – though in a sop to the poets, he allowed some wiggle room either way. Interestingly, not every number between 0 to 100 is covered by his scheme, though I’m not really sure why!

This idea of an agreed framework for understanding probability later jumped from the intelligence community to scientific disciplines. A recent review of surveys dating back to 1989 looked at how both patients and healthcare professionals interpret words such as “likely” in the context of a medical diagnosis or treatment, showing some overlap with Kent’s scheme, but it is not identical.

So, let’s come back to the question I asked at the start of this column – what does “very likely” mean in the context of climate change? Thankfully, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has set out exactly what it means in guidance on how scientists should convey uncertainty in their reports. Officially, “very likely” means that there is a 90 to 100 per cent chance of an event occurring – which, given that many climate researchers are now saying we have already passed 1.5°C, is unfortunately bang on target.

That said, nothing is ever that simple. Logically, “event A is likely to happen” and “event A is unlikely to be avoided” should be equivalent. But in a study published last year, researchers found that telling people a particular climate forecast is “unlikely” made them perceive it as being backed by poorer evidence, and with less of a consensus between climate scientists, than the equivalent “likely” statement. This may be because we have a cognitive bias to prefer positive framings over negative ones. The classic example is of a town of 600 people threatened by disease – when asked which treatment they prefer, most will go for the option that saves 200 lives, rather than the option that will see 400 die, even though these are equivalent.

So, what can you take from this? First, when communicating uncertainty, hard numbers really do help. But if you can’t do that – telling someone “there is a 75 per cent chance I will have pasta for dinner” is liable to get you odd looks – then try to make sure the people you are communicating with have a shared understanding of the words you are using, even if it isn’t written down in a Kent-like scheme. Finally, focus on the positive if you can – people will be more likely to believe your predictions. How much more likely? Well, I couldn’t possibly say.

Topics: