We may finally know what a healthy gut microbiome looks like

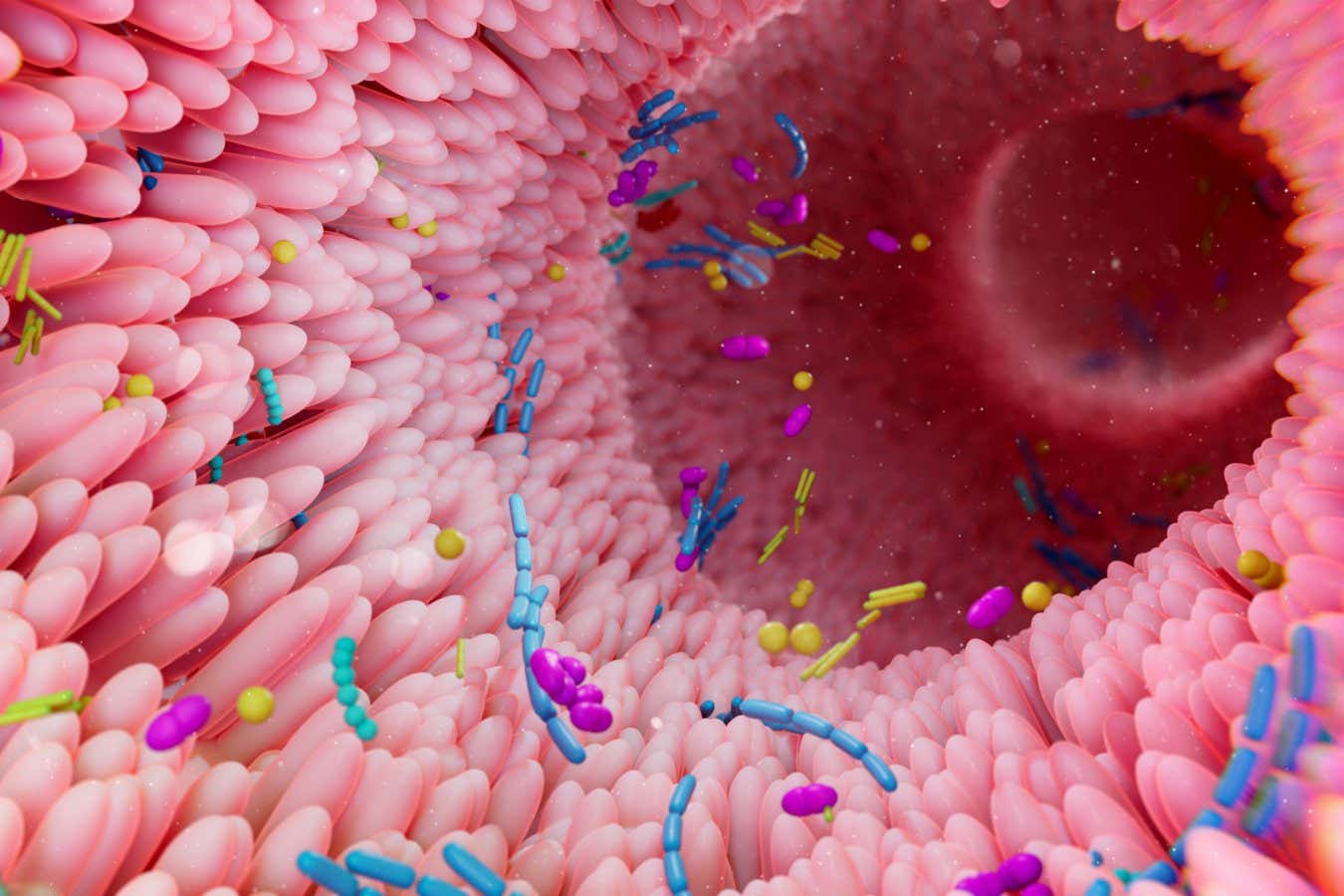

The trillions of microscopic bacteria that reside in our gut have an outsized role in our health THOM LEACH/SCIENCE

The trillions of microscopic bacteria that reside in our gut have an outsized role in our health

THOM LEACH/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

We often hear talk of things being good for our microbiome, and in turn, good for our health. But it wasn’t entirely clear what a healthy gut microbiome consisted of. Now, a study of more than 34,000 people has edged us closer towards understanding the mixes of microbes that reliably signal we have low inflammation, good immunity and healthy cholesterol levels.

Your gut microbiome can influence your immune system, rate of ageing and your risk of poor mental health. Despite a profusion of home tests promising to reveal the make-up of your gut community, their usefulness has been debated, because it is hard to pin down what a “good” microbial mix is.

Previous measures mainly looked at species diversity, with a greater array of bacteria being better. But it is difficult to identify particular communities of interacting organisms that are implicated in a specific aspect of our health, because microbiomes vary so much from person to person.

“There is a very intricate relationship between the food we eat, the composition of our gut microbiome and the effects the gut microbiome has on our health. The only way to try to map these connections is having large enough sample sizes,” says Nicola Segata at the University of Trento in Italy.

To create such a map, Segata and his colleagues have assessed a dataset from more than 34,500 people who took part in the PREDICT programme in the UK and US, run by microbiome testing firm Zoe, and validated the results against data from 25 other cohorts from Western countries.

Of the thousands of species that reside in the human gut, the researchers focused on 661 bacterial species that were found in more than 20 per cent of the Zoe participants. They used this to determine the 50 bacteria most associated with markers of good health – assessed via markers such as body mass index and blood glucose levels – and the 50 most linked to poor health.

The 50 “good bug” species – 22 of which are new to science – seem to influence four key areas: cholesterol levels; inflammation and immune health; body fat distribution; and blood sugar control.

The participants who were deemed healthy, because they had no known medical conditions, had about 3.6 more of these species than people with a condition, while people at a healthy weight hosted about 5.2 more of them than those with obesity.

The researchers suggest that good or bad health outcomes may come about due to the vital role the gut microbiome plays in releasing chemicals involved in cholesterol transport, inflammation reduction, fat metabolism and insulin sensitivity.

As to the specific species that were present, most microbes in both the “good” and “bad” rankings belong to the Clostridia class. Within this class, species in the Lachnospiraceae family featured 40 times, with 13 seemingly having favourable effects and 27 unfavourable.

“The study highlights bacterial groups that could be further investigated regarding their potential positive or negative impact [on] health conditions, such as high blood glucose levels or obesity,” says Ines Moura at the University of Leeds, UK.

The link between these microbes and diet was assessed via food questionnaires and data logged on the Zoe app, where users are advised to aim for at least 30 different plants a week and at least three portions a day of fermented foods, with an emphasis on fibre and not too many ultra-processed options.

The researchers found that most of the microbes either aligned with a generally healthy diet and better health, or with a worse diet and poorer health. But 65 of the 661 microbes didn’t fit in.

“These 65 bacteria are a testament to the fact that the picture is still more complex than what we saw,” says Segata, who also works as a consultant for Zoe. “The effects may depend on the other microbes that are there, or the specific strain of the bacterium or the specific diet.”

This sorting of “good” versus “bad” bacteria has enabled the researchers to create a 0 to 1000 ranking scale for the overall health of someone’s gut microbiota, which is already used as part of Zoe’s gut health tests.

“Think of a healthy gut microbiome as a community of chemical factories. We want large numbers of species, we want the good ones outnumbering the bad ones, and when you get that, then you’re producing really healthy chemicals, which have impacts across the body,” says team member Tim Spector at King’s College London, co-founder of Zoe.

This doesn’t mean the ideal healthy gut microbiome has been pinned down, though. “Defining a healthy microbiome is a difficult task, as the gut microbiome composition is impacted by diet, but it can also change with environmental factors, age and health conditions that require long-term medication,” says Moura.

“We really need to think about our body and our microbiome as two complex systems that together make one even more complex system,” says Segata. “When you change one thing, everything is modified a bit as a consequence. Understanding what is cause and effect in many cases can be very intricate.”

Bigger studies are needed to tease out these links and cover more of the global population, says Segata. However, once we have established the baseline of your health and microbiome, it should become possible to recommend specific foods to tweak your gut bacteria, he says.

Topics: