This reengineered HPV vaccine trains T cells to hunt down cancer

Over the last decade, scientists at Northwestern University have identified a key insight about how vaccines work. The ingredients

Over the last decade, scientists at Northwestern University have identified a key insight about how vaccines work. The ingredients matter, but the way those ingredients are physically arranged can dramatically influence performance.

After validating this concept in multiple studies, the researchers applied it to therapeutic cancer vaccines aimed at HPV-driven tumors. In their latest work, they found that simply adjusting the orientation and position of a single cancer targeting peptide significantly strengthened the immune system’s ability to attack tumors.

The study was published Feb. 11 in Science Advances.

Testing a Spherical Nucleic Acid Vaccine

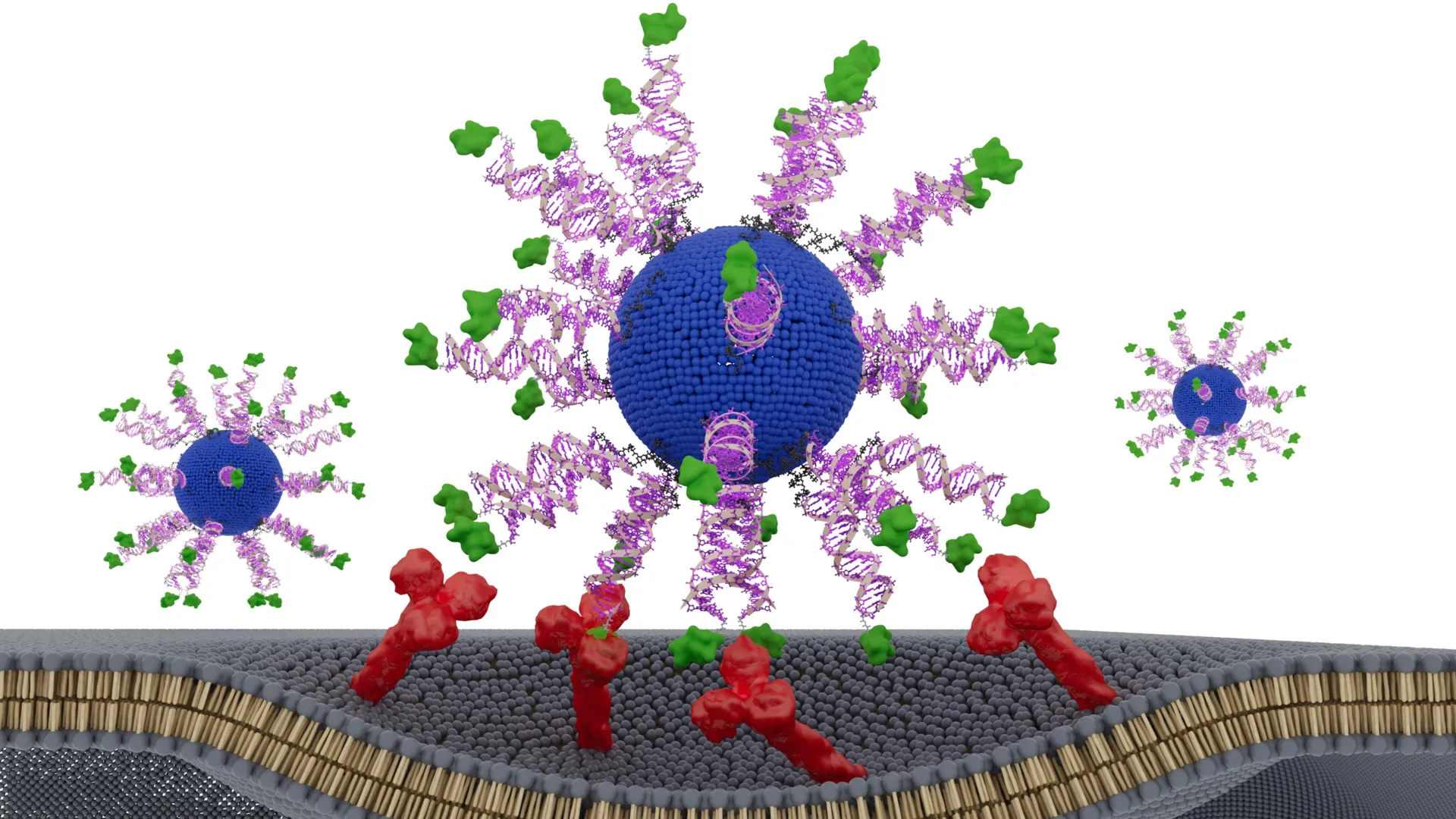

To explore this idea, the team created a vaccine built from a spherical nucleic acid (SNA), a globular DNA structure that naturally enters immune cells and activates them. They then intentionally reorganized the components within the SNA in several different configurations. Each version was evaluated in humanized animal models of HPV-positive cancer and in tumor samples taken from patients with head and neck cancer.

One configuration clearly delivered superior results. It reduced tumor growth, prolonged survival in animals and generated greater numbers of highly active cancer killing T cells. The findings show that even a small change in how vaccine components are arranged can determine whether a nanovaccine produces a limited immune response or a powerful tumor destroying effect.

This principle forms the foundation of an emerging field known as “structural nanomedicine,” a term introduced by Northwestern nanotechnology pioneer Chad A. Mirkin. The field centers on SNAs, which Mirkin invented.

“There are thousands of variables in the large, complex medicines that define vaccines,” said Mirkin, who led the study. “The promise of structural nanomedicine is being able to identify from the myriad possibilities the configurations that lead to the greatest efficacy and least toxicity. In other words, we can build better medicines from the bottom up.”

Mirkin is the George B. Rathmann Professor of Chemistry, Chemical and Biological Engineering, Biomedical Engineering, Materials Science and Engineering, and Medicine at Northwestern. He holds appointments in the Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences, McCormick School of Engineering and Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. He also directs the International Institute of Nanotechnology and is a member of the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University. He co-led the study with Dr. Jochen Lorch, a professor of medicine at Feinberg and the medical oncology director of the Head and Neck Cancer Program at Northwestern Medicine.

Moving Beyond the Traditional Vaccine Mixing Approach

Conventional vaccine development often involves combining key ingredients without precise structural control. In cancer immunotherapy, tumor derived molecules called antigens are paired with immune stimulating compounds known as adjuvants. These are mixed together and administered as a single formulation.

Mirkin describes this as the “blender approach,” where the components lack defined organization.

“If you look at how drugs have evolved over the last few decades, we have gone from well-defined small molecules to more complex but less structured medicines,” Mirkin said. “The COVID-19 vaccines are a beautiful example — no two particles are the same. While very impressive and extremely useful, we can do better, and, to create the most effective cancer vaccines, we will have to.”

Research from Mirkin’s laboratory shows that arranging antigens and adjuvants into carefully designed nanoscale structures can significantly improve outcomes. When configured properly, the same ingredients can deliver stronger effects with lower toxicity compared to unstructured mixtures.

The team has already used this structural nanomedicine strategy to design SNA vaccines targeting melanoma, triple negative breast cancer, colon cancer, prostate cancer and Merkel cell carcinoma. These candidates have shown encouraging results in preclinical studies, and seven SNA based drugs have advanced into human clinical trials for various diseases. SNAs are also incorporated into more than 1,000 commercial products.

Strengthening CD8 T Cell Response Against HPV Cancers

In the new study, the researchers focused on cancers caused by human papillomavirus, or HPV. HPV is responsible for most cervical cancers and an increasing percentage of head and neck cancers. While preventive HPV vaccines can stop infection, they do not treat cancers that have already developed.

To address this need, the team created therapeutic vaccines designed to activate CD8 “killer” T cells, the immune system’s most powerful cancer fighting cells. Each nanoparticle included a lipid core, immune activating DNA and a short fragment of an HPV protein already present in tumor cells.

Every version of the vaccine contained identical ingredients. The only variable was the position and orientation of the HPV derived peptide, or antigen. The researchers tested three designs. In one, the peptide was hidden inside the nanoparticle. In the other two, it was displayed on the surface. For the surface versions, the peptide was attached at either the N terminus or the C terminus, a subtle difference that can influence how immune cells recognize and process it.

The version that presented the antigen on the surface attached via its N-terminus produced the strongest immune reaction. It triggered up to eight times more interferon-gamma, an important anti tumor signal released by killer T cells. These T cells were substantially more effective at destroying HPV-positive cancer cells. In humanized mouse models, tumor growth slowed markedly. In tumor samples from HPV-positive cancer patients, cancer cell killing increased by twofold to threefold.

“This effect did not come from adding new ingredients or increasing the dose,” Lorch said. “It came from presenting the same components in a smarter way. The immune system is sensitive to the geometry of molecules. By optimizing how we attach the antigen to the SNA, the immune cells processed it more efficiently.”

Redesigning Cancer Vaccines With Precision and AI

Mirkin now plans to reexamine earlier vaccine candidates that showed potential but failed to generate sufficiently strong immune responses in patients. By demonstrating that nanoscale structure directly influences immune potency, this research offers a framework for improving therapeutic cancer vaccines using existing components. That strategy could speed development and reduce costs.

He also anticipates that artificial intelligence will become an important tool in vaccine design. Machine learning systems could rapidly analyze vast numbers of structural combinations to identify the most effective arrangements.

“This approach is poised to change the way we formulate vaccines,” Mirkin said. “We may have passed up perfectly acceptable vaccine components because simply because they were in the wrong configurations. We can go back to those and restructure and transform them into potent medicines. The whole concept of structural nanomedicines is a major train roaring down the tracks. We have shown that structure matters — consistently and without exception.”

The study, “E711-19 placement and orientation dictate CD8+ T cell response in structurally defined spherical nucleic acid vaccines,” was supported by the National Cancer Institute (award numbers R01CA257926 and R01CA275430), the Lefkofsky Family Foundation and Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University.