The Moon is still shrinking and it could trigger more moonquakes

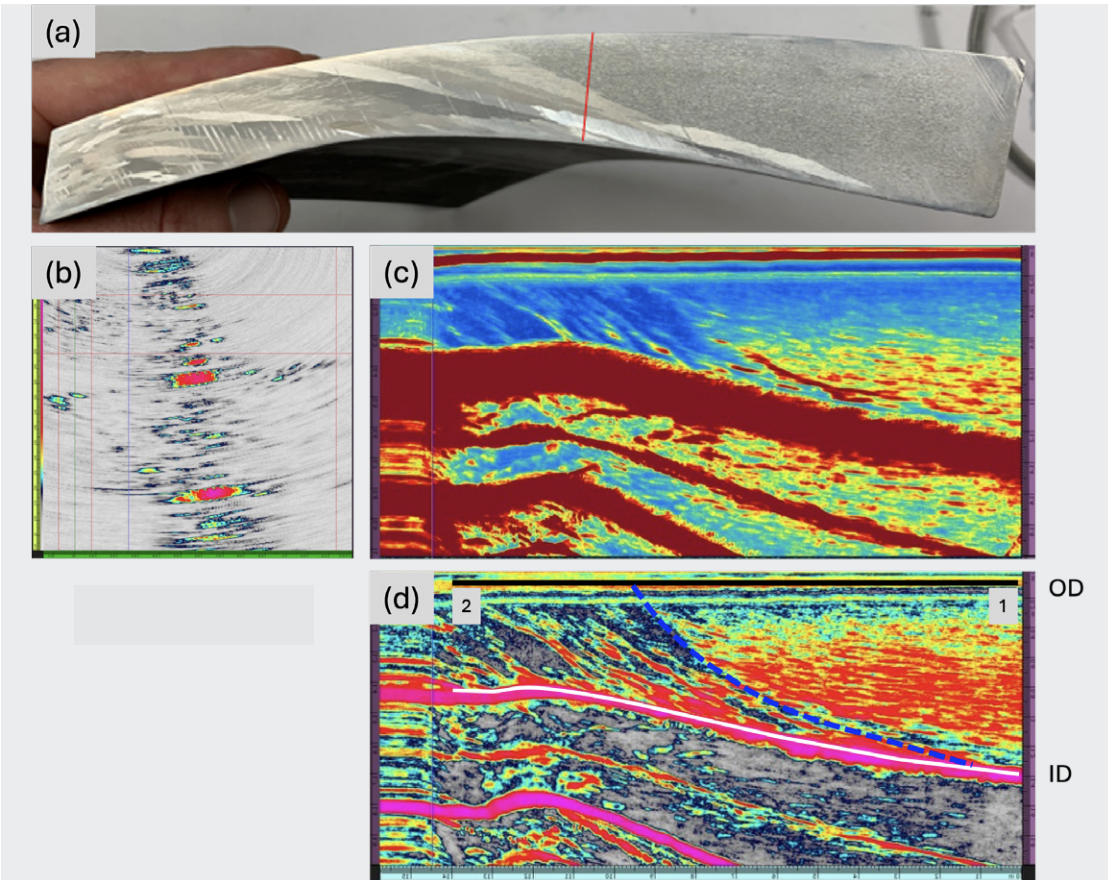

Researchers have created the first worldwide map and detailed study of small mare ridges (SMRs), subtle geological features that

Researchers have created the first worldwide map and detailed study of small mare ridges (SMRs), subtle geological features that signal tectonic activity on the Moon. The findings, published in The Planetary Science Journal, come from scientists at the National Air and Space Museum’s Center for Earth and Planetary Studies and their collaborators.

For the first time, scientists show that these ridges are relatively young and spread widely across the lunar maria, the broad, dark plains visible from Earth. By determining how SMRs form, the team has also identified new potential sources of moonquakes that could influence where future lunar missions choose to land.

How the Moon’s Tectonics Differ From Earth’s

Both Earth and the Moon experience tectonic forces, but they operate very differently. On Earth, the crust is broken into moving plates that collide, pull apart, and grind past one another. Those motions build mountain ranges, carve deep ocean trenches, and fuel volcanic activity around the Pacific.

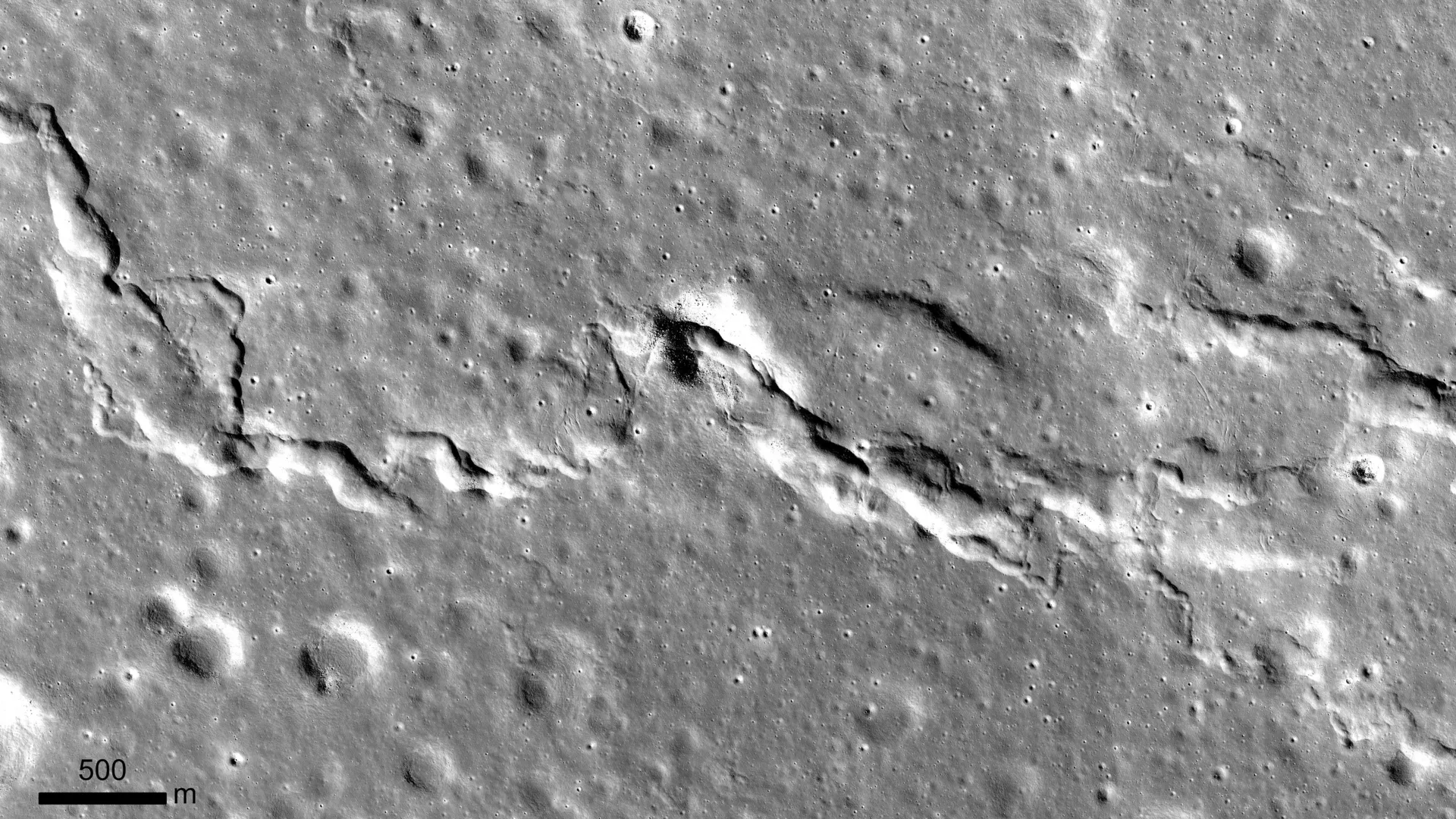

The Moon does not have plate tectonics. Instead, stress builds up within its single, continuous crust. That stress produces distinctive landforms. One well known example is lobate scarps, ridges created when the crust compresses and one section is pushed up and over another along a fault. These scarps are common in the lunar highlands and formed within the last billion years, about the most recent 20% of the Moon’s history.

A Shrinking Moon and the Rise of SMRs

In 2010, co author Tom Watters, a senior scientist emeritus at the Center for Earth and Planetary Studies, found evidence that the Moon is gradually shrinking. As the interior cools, the surface contracts, creating the compressional forces that formed lobate scarps in the highlands.

However, lobate scarps do not explain all of the Moon’s relatively recent contraction features. Another class of landforms, small mare ridges, has also been identified.

SMRs form from the same compressional forces that create lobate scarps. The difference lies in location. Lobate scarps appear in the highlands, while SMRs are found only in the maria. The research team set out to systematically map these ridges across the lunar maria and investigate their role in recent tectonic activity.

“Since the Apollo era, we’ve known about the prevalence of lobate scarps throughout the lunar highlands, but this is the first time scientists have documented the widespread prevalence of similar features throughout the lunar mare,” said Cole Nypaver, a post doctoral research geologist at the Center for Earth and Planetary Studies and the first author on the paper. “This work helps us gain a globally complete perspective on recent lunar tectonism on the moon, which will lead to a greater understanding of its interior and its thermal and seismic history, and the potential for future moonquakes.”

Thousands of Young Ridges Identified

The team assembled the first comprehensive catalog of SMRs. In the process, they identified 1,114 previously unrecognized SMR segments across the near side lunar maria. That brings the total number of known SMRs on the Moon to 2,634.

Their analysis indicates that the average SMR is about 124 million years old. That closely matches the average age of lobate scarps (105 million years old) determined in earlier research by Watters and colleagues. These comparable ages suggest that SMRs, like lobate scarps, rank among the Moon’s youngest geological features.

The study also shows that SMRs form along the same types of faults as lobate scarps. In some regions, scarps in the highlands transition into SMRs within the maria, reinforcing the idea that both structures share a common origin. When combined with existing data on lobate scarps, the new SMR catalog offers a far more complete picture of the Moon’s recent contraction and tectonic evolution.

“Our detection of young, small ridges in the maria, and our discovery of their cause, completes a global picture of a dynamic, contracting moon,” Watters said.

What This Means for Moonquakes and Future Missions

Earlier work by Watters linked the tectonic forces that produce lobate scarps with recorded moonquakes. Because SMRs form through the same type of faulting, moonquakes may also occur across the lunar maria wherever these ridges exist.

Expanding the map of potential moonquake sources provides scientists with new opportunities to study the Moon’s interior and tectonic behavior. At the same time, it highlights possible seismic risks for astronauts who may one day explore or live on the lunar surface.

“We are in a very exciting time for lunar science and exploration,” Nypaver said. “Upcoming lunar exploration programs, such as Artemis, will provide a wealth of new information about our moon. A better understanding of lunar tectonics and seismic activity will directly benefit the safety and scientific success of those and future missions.”