The invisible energy cost that keeps life from falling apart

Living systems pay energetic costs that traditional mechanical physics does not account for. One clear example is the energy

Living systems pay energetic costs that traditional mechanical physics does not account for. One clear example is the energy needed to keep certain biochemical processes running, such as those involved in photosynthesis, while actively preventing other chemical reactions from taking place. In classical mechanics, if nothing moves, no work is done, meaning there is no energy cost associated with stopping something from happening. However, more advanced thermodynamic calculations show that this assumption does not hold for living systems. These hidden costs are real and can be surprisingly large.

A new study published today (January 6) in the Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment (JSTAT) introduces a thermodynamic framework that makes it possible to calculate these previously overlooked energy expenses. The approach offers a new way to understand how metabolic pathways were selected and refined during the earliest stages of life on Earth.

How Early Life Learned to Control Chemistry

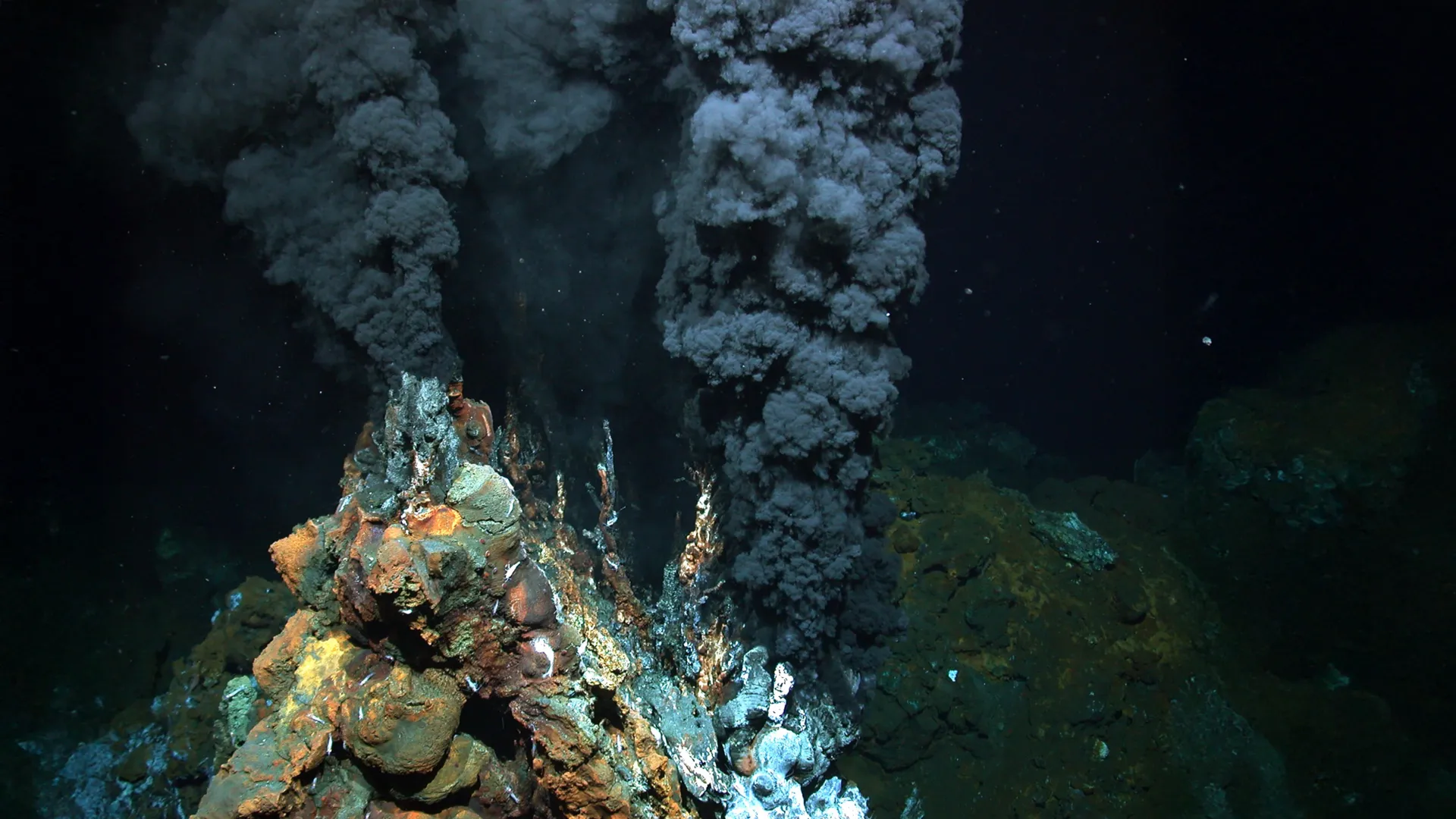

Life likely began when simple organic molecules formed a boundary separating an interior from the surrounding environment. This first cell membrane created a clear distinction between inside and outside. From that point on, the system had to spend energy to maintain this separation and to limit which chemical reactions could occur internally. Instead of allowing every possible reaction, early cells selected only a small set of metabolic pathways that could use incoming materials from the “outside” to produce useful new compounds. The emergence of life was inseparable from this need to manage boundaries and choices.

While metabolism has obvious energy costs tied to chemical reactions themselves, there is also an additional cost associated with guiding chemical activity along specific pathways. This extra effort prevents reactions from branching into all other physically possible alternatives. From the perspective of classical mechanics, these boundary conditions and reaction constraints should not require energy, because they are treated as fixed and external. In reality, they contribute to entropy production and carry an energetic price.

A New Way to Measure Metabolic Efficiency

Praful Gagrani, a researcher at the University of Tokyo and lead author of the study, worked with colleagues Nino Lauber (University of Vienna), Eric Smith (Georgia Institute of Technology and Earth-Life Science Institute), and Christoph Flamm (University of Vienna) to develop a method for calculating these hidden costs. Their approach allows scientists to rank metabolic pathways based on how energetically demanding they are, offering valuable insight into biological efficiency and evolution.

“What inspired the new work is that Eric Smith, one of the co-authors, used MØD, a software developed by Flamm and co-workers, to enumerate all the possible pathways that can ‘build’ organic molecules starting from CO2.”

Gagrani points to earlier research by Smith and colleagues on the Calvin cycle, the series of reactions in photosynthesis that converts carbon dioxide into glucose.

“Eric used the algorithm to enumerate all the pathways that can make the same conversion that the Calvin cycle does, and then he used what we now call the maintenance cost in our paper to rank them.”

That analysis revealed that the pathway used by nature ranks among the least dissipative options, meaning it requires less energy than most alternatives. “Awesome, isn’t it?,” Gagrani remarks.

Measuring Improbability Instead of Energy

Building on this insight, the research team developed a general method to systematically estimate the thermodynamic costs of metabolism. In their model, a cell is treated as a system with a steady flow, where one molecule enters, such as a nutrient, and another exits, such as a product or waste. Based on the chemistry involved, scientists can generate every possible reaction pathway that connects the input to the output. Each pathway carries its own thermodynamic cost.

Rather than calculating energy in the traditional sense, the method evaluates how unlikely it would be for a particular reaction network to operate in exactly that way if chemistry were driven only by spontaneous processes. The more improbable the behavior, the higher its cost.

This improbability has two parts. The first is the maintenance cost, which reflects how difficult it is to sustain a steady flow through a specific pathway. The second is the restriction cost, which measures how hard it is to suppress all alternative reactions while keeping only the desired pathway active.

Together, these factors define the overall cost of a metabolic process. This allows researchers to compare pathways and determine how energetically demanding it is for a cell to favor one chemical route while silencing others.

Why Nature Chooses Certain Pathways

The researchers found some unexpected patterns. “We saw things we didn’t expect, but that make sense once you think about them,” Gagrani says. “For example, that using multiple pathways at the same time is less costly than using just one. Here’s an analogy: imagine four people who need to go from A to B through narrow tunnels. If each person has their own tunnel — four tunnels — they arrive more quickly than if there are only three or fewer, because two or more people would obstruct each other in the same narrow passage.”

Yet real biological systems often rely on a single dominant pathway. Gagrani explains why. “It’s true, but in biological systems catalysis often intervenes — the action of facilitating molecules, enzymes — which accelerate reactions and make them less costly, achieving the same effect as having multiple pathways in parallel. This evolutionary choice happens because maintaining many pathways can have other drawbacks, such as producing many potentially toxic molecules.”

A New Tool for Studying Life’s Origins

“Our method,” Gagrani concludes, “is a useful tool for studying the origin and evolution of life because it allows us to evaluate the costs of choosing and maintaining specific metabolic processes. It helps us understand how certain pathways arise — but explaining why those particular ones were selected requires a truly multidisciplinary effort.”