Sugar-free sweeteners may still be harming your liver

Sweeteners such as aspartame, found in Equal packets, sucralose (Splenda), and sugar alcohols are widely promoted as healthier options

Sweeteners such as aspartame, found in Equal packets, sucralose (Splenda), and sugar alcohols are widely promoted as healthier options than foods made with refined sugar (glucose). Many people turn to these alternatives hoping to reduce health risks linked to sugar.

New scientific evidence is now calling that belief into question. Recent findings suggest that the sugar alcohol sorbitol may not be as harmless as it is often assumed to be.

New research raises concerns about sugar substitutes

The findings come from a study published in Science Signaling that builds on years of research into how fructose affects the liver and other organs. The work comes from the laboratory of Gary Patti at Washington University in St. Louis.

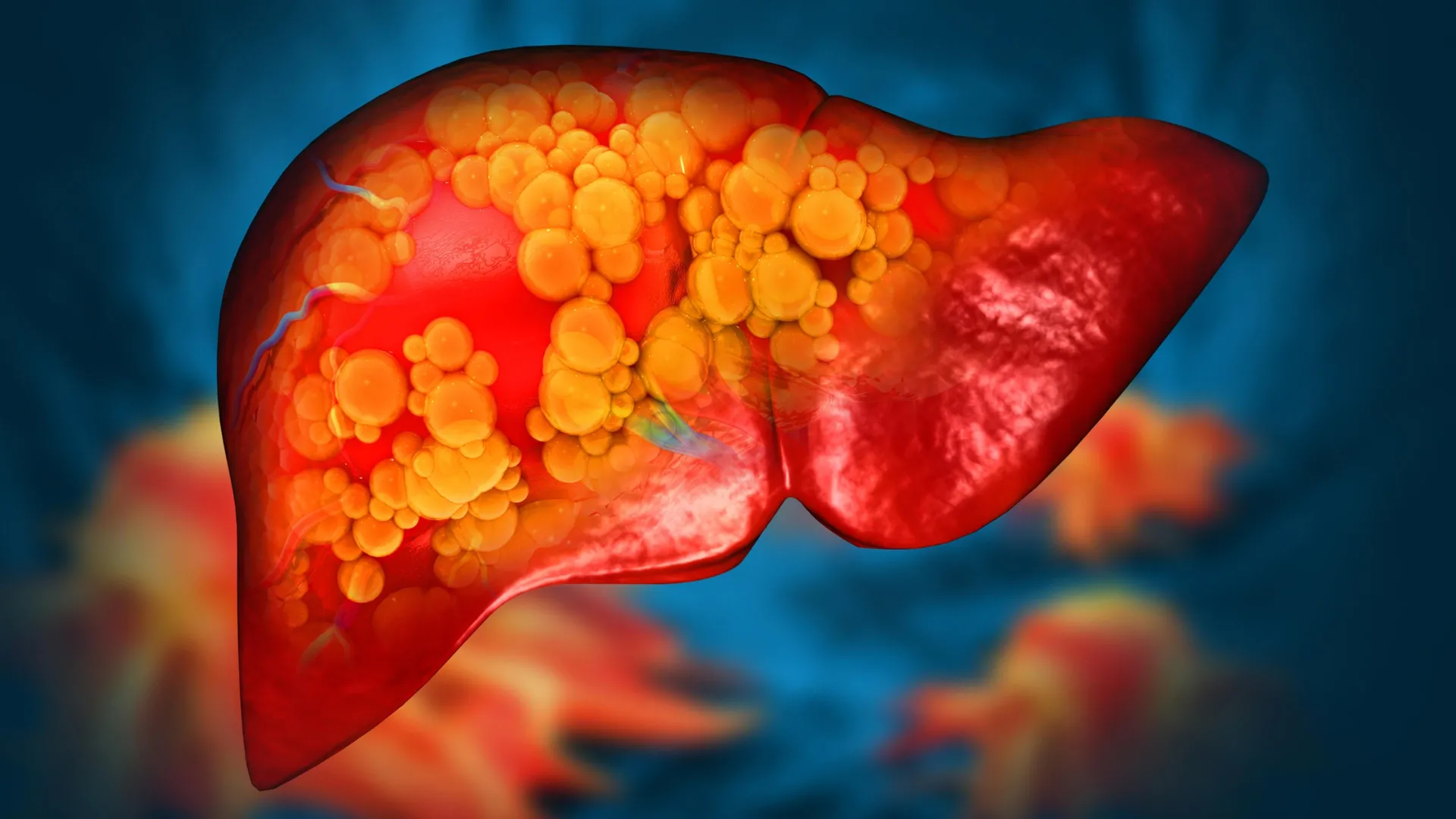

Patti, the Michael and Tana Powell Professor of Chemistry in Art & Sciences and of genetics and medicine at WashU Medicine, has previously shown that fructose processed by the liver can be diverted in ways that fuel cancer cell growth. Other studies have linked fructose to steatotic liver disease, a condition that now affects about 30% of adults worldwide.

Sorbitol’s close connection to fructose

One of the most unexpected results of the new study is that sorbitol is essentially “one transformation away from fructose,” according to Patti. Because of this close relationship, sorbitol can trigger effects similar to those caused by fructose itself.

Using zebrafish as a model, the researchers showed that sorbitol, commonly found in “low-calorie” candies and gums and naturally present in stone fruits, can be produced inside the body. Enzymes in the gut can generate sorbitol, which is then transported to the liver and converted into fructose.

The team also discovered that the liver can receive fructose through multiple metabolic routes. Which pathway dominates depends on how much glucose and sorbitol a person consumes, as well as the specific mix of bacteria living in their gut.

How the gut produces sorbitol after eating

Most earlier studies of sorbitol metabolism focused on disease states such as diabetes, where high blood sugar leads to excess sorbitol production. Patti explained that sorbitol can also be created naturally in the gut after a meal, even in people without diabetes.

The enzyme responsible for making sorbitol does not bind easily to glucose, meaning glucose levels must rise significantly before the process begins. That is why sorbitol production has long been linked to diabetes. However, the zebrafish experiments showed that glucose levels in the intestine can become high enough after eating to activate this pathway even under normal conditions.

“It can be produced in the body at significant levels,” said Patti. “But if you have the right bacteria, turns out, it doesn’t matter.”

The role of gut bacteria in sorbitol breakdown

Certain Aeromonas bacterial strains are able to break down sorbitol and convert it into a harmless bacterial byproduct. When these bacteria are present and functioning well, sorbitol is less likely to cause problems.

“However, if you don’t have the right bacteria, that’s when it becomes problematic. Because in those conditions, sorbitol doesn’t get degraded and as a result, it is passed on to the liver,” he said.

Once sorbitol reaches the liver, it is converted into a fructose derivative. This raises concerns about whether alternative sweeteners truly offer a safer option than table sugar, especially for people with diabetes and other metabolic disorders who often rely on products labeled as “sugar free.”

When sorbitol intake overwhelms the system

At low levels, such as those typically found in whole fruits, gut bacteria are usually effective at clearing sorbitol. Trouble begins when the amount of sorbitol exceeds what these microbes can handle.

This overload can happen when large amounts of glucose are consumed, leading to increased production of sorbitol from glucose, or when the diet itself contains high levels of sorbitol. Even individuals with helpful bacteria may run into problems if their intake of glucose and sorbitol becomes too high, since the microbes can be overwhelmed.

Avoiding both sugar and sugar substitutes has become increasingly difficult, as many processed foods contain several forms of sweeteners at once. Patti was surprised to learn that his own favorite protein bar contained a significant amount of sorbitol.

Rethinking the safety of sugar alcohols

Further research is needed to understand exactly how gut bacteria clear sorbitol. What is becoming clear, however, is that the long-held assumption that sugar alcohols, also known as polyols, are simply eliminated without harm may not be accurate.

“We do absolutely see that sorbitol given to animals ends up in tissues all over the body,” he said.

The overall message from the research is that replacing sugar is not as simple as it may seem. As Patti put it, “there is no free lunch” when it comes to sugar alternatives, and many metabolic pathways can ultimately lead back to liver dysfunction.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, grants R35ES028365 (G.J.P.) and P30DK056341 (S.K.).