Sinking river deltas put millions at risk of flooding

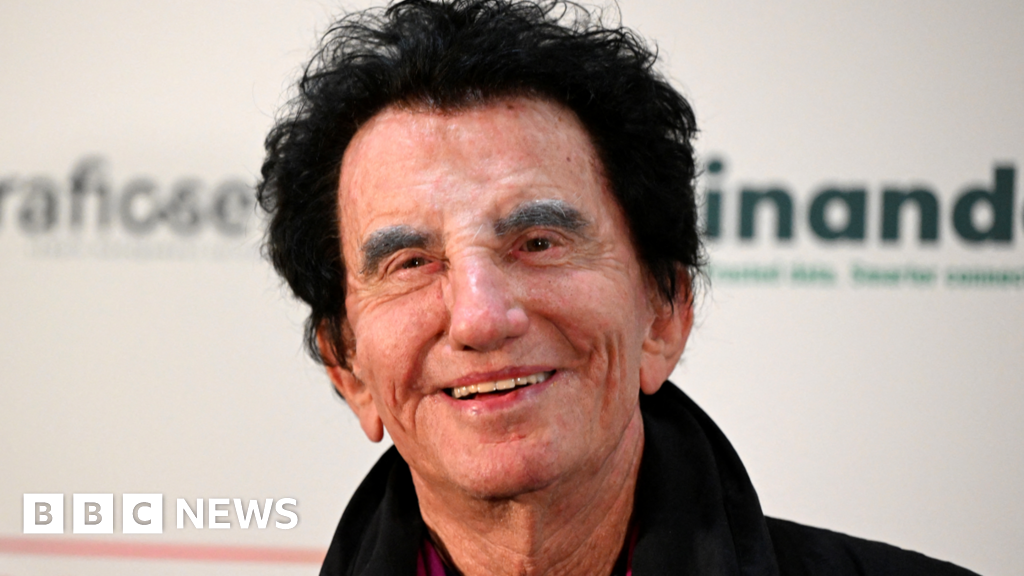

The Chao Phraya river delta in Thailand is one of the fastest-sinking regions in the world Chanon Kanjanavasoontara/Getty Images

The Chao Phraya river delta in Thailand is one of the fastest-sinking regions in the world

Chanon Kanjanavasoontara/Getty Images

The world’s most economically and environmentally important river deltas are sinking, putting millions of people at risk of flooding. In most cases, the sinking of river deltas poses a greater threat to the communities that live on them than sea level rise, according to an analysis of satellite data.

Up to half a billion humans live on river deltas, including some of the poorest populations on Earth. Ten megacities with a population over 10 million people are located within these vast low-lying areas.

Manoochehr Shirzaei at Virginia Tech and his colleagues attempted to determine the rate at which 40 river deltas around the world are sinking, including the Mekong, Mississippi, Amazon, Zambezi, Yangtze and Nile.

Subsidence causes a double whammy of inundation, says Shirzaei, because, at the same time as deltas are sinking, global sea levels are rising at about 4 millimetres per year.

The team used data from 2014 to 2023 obtained by the European Space Agency’s Sentinel 1 satellite radar, which can measure changes in the distance between the satellite and the ground to an accuracy within 0.5 mm. In all 40 deltas, more than a third of each area is sinking, while in 38 out of the 40, more than half of the area is.

“In many, sinking land is a bigger driver of relative sea-level rise than the ocean itself,” says Shirzaei. “Average subsidence exceeds sea-level rise in 18 of 40 deltas, and the dominance is even stronger in the lowest-lying areas, less than a metre above sea level.”

Thailand’s Chao Phraya delta, where Bangkok is located, is faring the worst out of the 40 in terms of the rate of sinking and area affected. It has an average subsidence rate of 8 mm per year – twice the current global mean sea-level rise – and 94 per cent of the delta area is subsiding faster than 5 mm per year.

The combined effect of sinking land and rising seas means Bangkok and the Chao Phraya delta face sea levels rising at the rate of 12.3 millimetres per year. Alexandria in Egypt and the Indonesian cities of Jakarta and Surabaya are also facing rapid subsidence.

The team also looked at data on three major human pressures – groundwater extraction, sediment alteration and urban expansion – to determine which was having the greatest impact on subsidence of the deltas. Upstream dams, levees and river engineering can reduce sediment delivery that would otherwise help deltas build or maintain elevation, says Shirzaei. Meanwhile, urban expansion puts more load on the delta surface and often increases water demand, which can indirectly intensify groundwater depletion.

Among those factors, groundwater extraction has the strongest overall influence, but some deltas are more influenced by sediment changes and urban expansion, the researchers found.

Shirzaei says it is a mistake for policy-makers to only focus on sea level rise caused by climate change and this risks misdirecting adaptation efforts. “Unlike global sea-level rise, human-driven subsidence is often locally addressable by groundwater regulation, managed aquifer recharge and sediment management,” he says.

Data centres, which use vast amounts of water for cooling, could contribute to the problem, says Shirzaei. “Our study shows that groundwater extraction is the leading driver of rapid land subsidence in many river deltas, and water-intensive facilities such as data centres can worsen this risk if they rely on local water supplies,” he says.

In already vulnerable regions like the Mekong delta, added water demand can accelerate sinking land, undermine drainage and flood protection systems and shorten the lifespan of critical infrastructure. “This doesn’t mean data centres should never be built on deltas, but it does mean they must avoid groundwater use, minimise water demand and explicitly account for subsidence,” says Shirzaei.

Topics: