Scientists solve a major roadblock holding back cancer cell therapy

For the first time, researchers at the University of British Columbia have shown how to consistently produce a crucial

For the first time, researchers at the University of British Columbia have shown how to consistently produce a crucial type of human immune cell, known as helper T cells, from stem cells in a controlled lab setting.

The research, published on January 7 in Cell Stem Cell, removes a major barrier that has slowed the development, affordability, and large-scale production of cell therapies. By solving this problem, the work could help make off-the-shelf treatments more accessible and effective for conditions such as cancer, infectious diseases, autoimmune disorders, and more.

“Engineered cell therapies are transforming modern medicine,” said co-senior author Dr. Peter Zandstra, professor and director of the UBC School of Biomedical Engineering. “This study addresses one of the biggest challenges in making these lifesaving treatments accessible to more people, showing for the first time a reliable and scalable way to grow multiple immune cell types.”

The Promise and Limits of Living Drugs

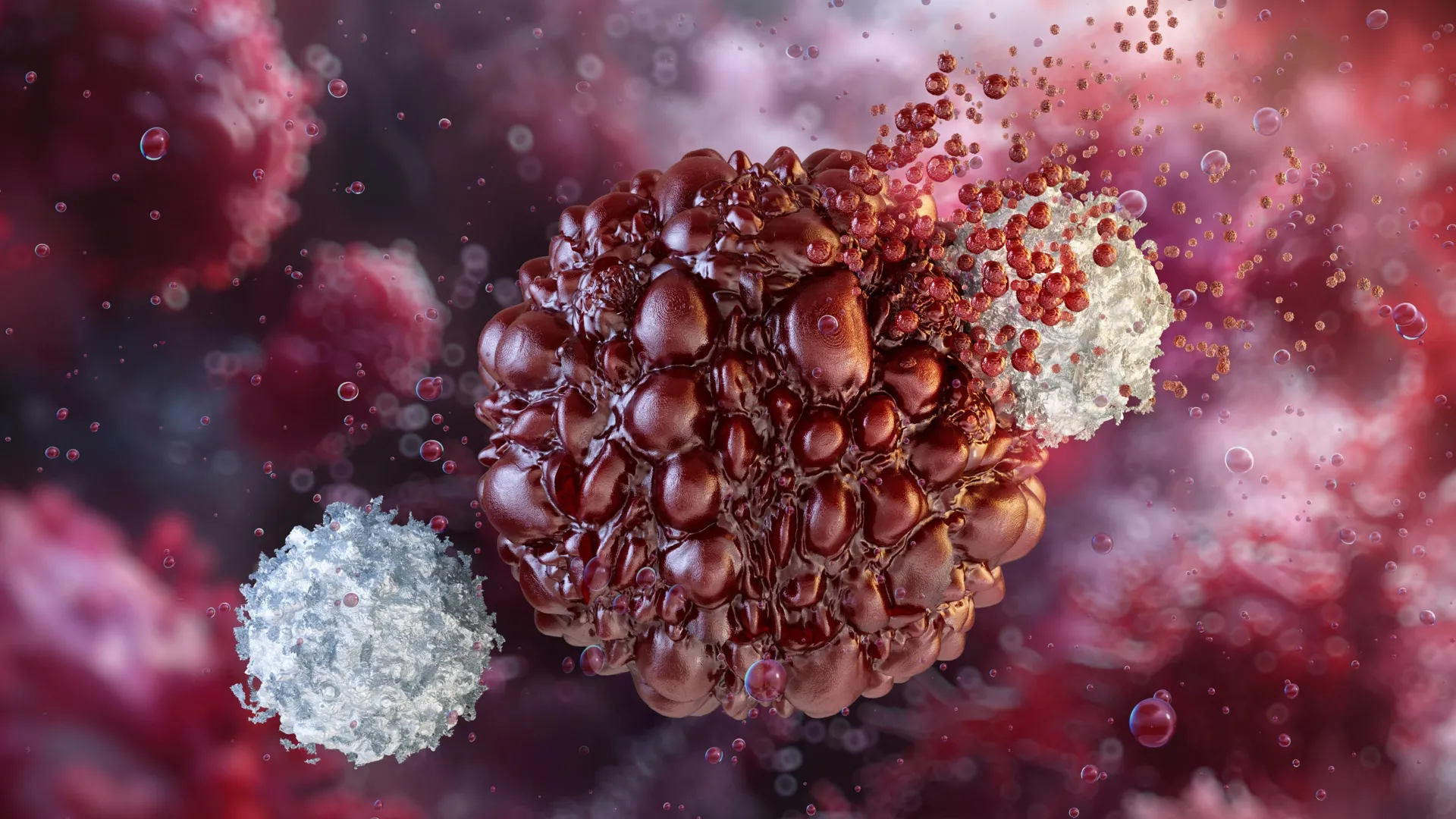

Over the past several years, engineered cell therapies such as CAR-T treatments have produced dramatic, sometimes lifesaving results for people with cancers that were once considered untreatable. These therapies work by reprogramming a patient’s immune cells to recognize and destroy disease, effectively turning those cells into ‘living drugs’.

Even with their success, cell therapies remain costly, complex to manufacture, and out of reach for many patients around the world. One key reason is that most existing treatments rely on a patient’s own immune cells, which must be collected and specially prepared over several weeks for each individual.

“The long-term goal is to have off-the-shelf cell therapies that are manufactured ahead of time and on a larger scale from a renewable source like stem cells,” said co-senior author Dr. Megan Levings, a professor of surgery and biomedical engineering at UBC. “This would make treatments much more cost-effective and ready when patients need them.”

Cancer cell therapies are most effective when two types of immune cells work together. Killer T cells directly attack infected or cancerous cells. Helper T cells, which act as the immune system’s conductors — detecting health threats, activating other immune cells and sustaining the immune responses over time — play a central coordinating role.

While scientists have made progress using stem cells to create killer T cells in the lab, they have not been able to reliably generate helper T cells until now.

“Helper T cells are essential for a strong and lasting immune response,” said Dr. Levings. “It’s critical that we have both to maximize the efficacy and flexibility of off-the-shelf therapies.”

A Key Advance Toward Stem Cell Based Immune Therapies

In the new study, the UBC research team addressed this long-standing challenge by carefully adjusting biological signals that guide how stem cells develop. This approach allowed them to precisely control whether stem cells became helper T cells or killer T cells.

The scientists found that a developmental signal known as Notch plays an important but time-sensitive role in immune cell formation. Notch is necessary early in development, but if the signal stays active for too long, it blocks the formation of helper T cells.

“By precisely tuning when and how much this signal is reduced, we were able to direct stem cells to become either helper or killer T cells,” said co-first author Dr. Ross Jones, a research associate in the Zandstra Lab. “We were able to do this in controlled laboratory conditions that are directly applicable in real-world biomanufacturing, which is an essential step toward turning this discovery into a viable therapy.”

The team also confirmed that the lab-grown helper T cells functioned like real immune cells, not just in appearance but in behavior. The cells showed signs of full maturity, carried a wide variety of immune receptors, and were able to develop into specialized subtypes with distinct immune roles.

“These cells look and act like genuine human helper T cells,” said co-first author Kevin Salim, a UBC PhD student in the Levings Lab. “That’s critical for future therapeutic potential.”

Researchers say the ability to generate both helper and killer T cells, and to carefully control their balance, could greatly improve the effectiveness of stem cell-derived immune therapies.

“This is a major step forward in our ability to develop scalable and affordable immune cell therapies,” said Dr. Zandstra. “This technology now forms the foundation for testing the role of helper T cells in supporting the elimination of cancer cells and generating new types of helper T cell-derived cells, such as regulatory T cells, for clinical applications.”