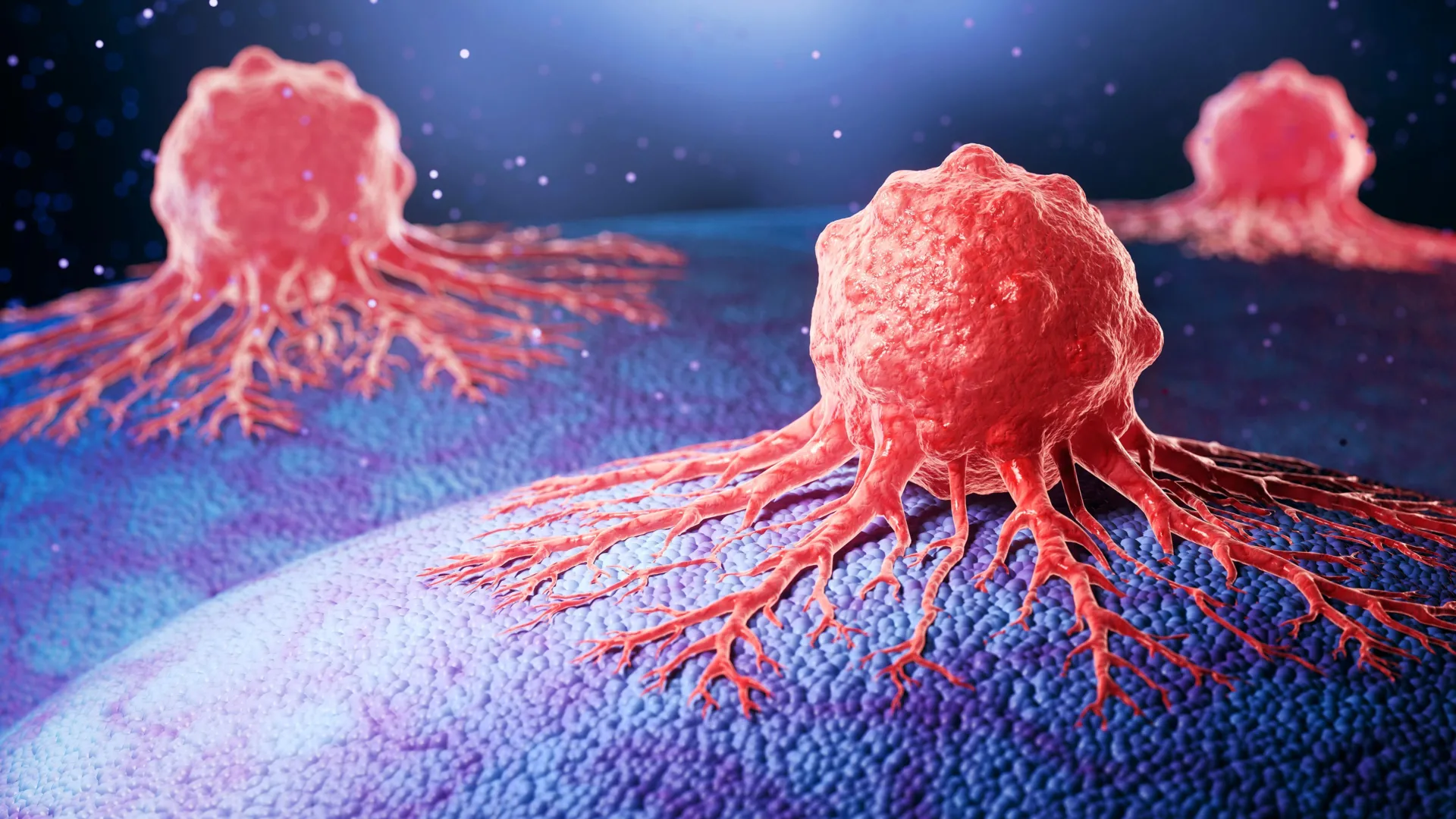

Scientists exposed how cancer hides in plain sight

Could this discovery change how cancer is treated in the future? In laboratory studies, the answer appears promising. An

Could this discovery change how cancer is treated in the future? In laboratory studies, the answer appears promising. An international team of scientists has uncovered a key biological process that helps pancreatic cancer grow and evade the immune system. By disrupting this process, researchers were able to dramatically shrink tumors in animal experiments.

The findings reveal a central way cancer cells protect themselves from immune attack. When this protective mechanism was blocked, tumors in laboratory animals rapidly collapsed, suggesting a powerful new vulnerability in one of the deadliest forms of cancer.

Published Findings and Global Collaboration

The study was published in the journal Cell and was led by an international group of researchers. Much of the experimental work was carried out by Leonie Uhl, Amel Aziba, and Sinah Löbbert, along with collaborators from the University of Würzburg (JMU), the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (USA), and Würzburg University Hospital.

Martin Eilers, Chair of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at JMU, led the research as part of the Cancer Grand Challenges KOODAC* team. Funding support came from Cancer Research UK, the Children Cancer Free Foundation (Kika), and the French National Cancer Institute (INCa) through the Cancer Grand Challenges initiative. Additional funding was provided by an Advanced Grant from the European Research Council awarded to Eilers.

The Protein That Drives Cancer Growth

The researchers focused on MYC, a protein that has been studied for decades in cancer biology. MYC is known as an oncoprotein because it plays a major role in pushing cells to divide. “In many types of tumors, this protein is one of the central drivers of cell division and thus of uncontrolled tumor growth,” explains Martin Eilers.

What remained unclear was how tumors with very high MYC activity avoid being detected by the immune system. Despite growing rapidly, MYC-driven tumors often fail to trigger an immune response, allowing them to spread unchecked.

MYC Takes on a Second Role Under Stress

The new study provides an answer. The researchers discovered that MYC has two distinct functions. Under normal conditions, MYC binds to DNA and switches on genes that promote cell growth. But in the stressful environment inside fast-growing tumors, MYC changes its behavior.

Instead of attaching to DNA, MYC begins binding to newly produced RNA molecules. This shift leads multiple MYC proteins to cluster together, forming dense groupings called multimers that act like molecular condensates.

These condensates function as gathering sites inside the cell, drawing in other proteins, especially the exosome complex, and concentrating them in one location.

Silencing the Cell’s Internal Alarm System

The exosome complex plays a cleanup role inside cells. In this case, it selectively breaks down RNA-DNA hybrids, which are faulty byproducts of gene activity. Normally, these hybrids act as distress signals, alerting the immune system that something is wrong inside the cell.

By organizing the destruction of these hybrids, MYC effectively shuts down this alarm system before it can activate immune defenses. As a result, the signaling process never begins, and immune cells fail to recognize the tumor as a threat.

A Separate Function That Enables Immune Evasion

The team showed that this immune-hiding ability depends on a specific RNA-binding region within the MYC protein. Importantly, this region is not needed for MYC’s role in driving cell growth, meaning the two functions operate independently.

The researchers demonstrated that MYC’s ability to promote tumor growth and its ability to suppress immune detection are mechanistically separate processes.

Tumors Collapse When the Shield Is Removed

To test the implications, scientists altered MYC so it could no longer bind RNA. Without this function, MYC could not recruit the exosome complex or suppress immune alarms.

The results in animal models were striking. “While pancreatic tumors with normal MYC increased in size 24-fold within 28 days, tumors with a defective MYC protein collapsed during the same period and shrank by 94 percent, but only if the animals’ immune systems were intact,” says Martin Eilers.

This confirmed that immune activity was essential for the tumor collapse.

A More Precise Target for Future Therapies

The findings open new possibilities for cancer treatment. Past efforts to shut down MYC entirely have failed because the protein is also critical for healthy cells. Targeting it broadly can cause serious side effects.

The newly identified mechanism offers a more focused approach. “Instead of completely switching off MYC, future drugs could specifically inhibit only its ability to bind RNA. This would potentially leave its growth-promoting function untouched, but lift the tumor’s cloak of invisibility,” explains Eilers. This could allow the immune system to recognize and attack the cancer again.

What Comes Next

Despite the promise, the researchers caution that clinical applications are still far off. Future work will need to determine how immune-activating RNA-DNA hybrids leave the cell nucleus and how MYC’s RNA-binding activity shapes the tumor’s local environment.

Dr David Scott, Director of Cancer Grand Challenges, highlighted the broader significance of the work: “Cancer Grand Challenges exists to support international teams like KOODAC that are pushing the boundaries of what we know about cancer. Research like this shows how uncovering the mechanisms tumors use to hide from the immune system can open up new possibilities, not only for adult cancers but also for childhood cancers that are the focus of the KOODAC team. It’s an encouraging example of how international collaboration and diverse expertise can help tackle some of the toughest challenges in cancer research.”

About Cancer Grand Challenges

Founded in 2020 by Cancer Research UK and the National Cancer Institute, Cancer Grand Challenges brings together leading research teams from around the world to address the most difficult problems in cancer science. These challenges are too complex for any single institution or country to solve alone.

With funding awards of up to £20m, the program enables teams to cross traditional scientific and geographic boundaries to accelerate progress against cancer.