Scientists are building viruses from scratch to fight superbugs

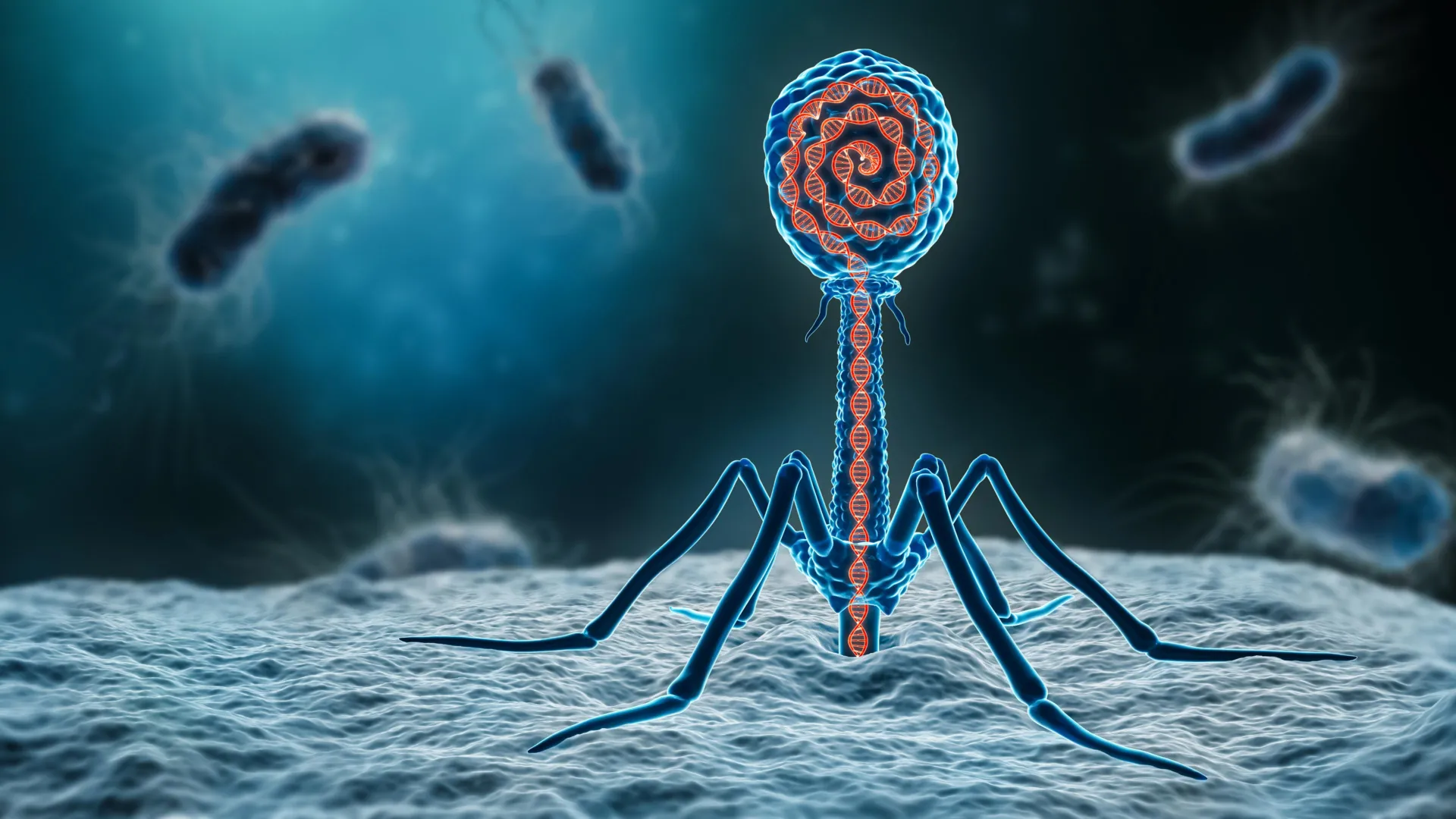

Bacteriophages, viruses that infect bacteria, have been used as medical treatments for bacterial infections for more than 100 years.

Bacteriophages, viruses that infect bacteria, have been used as medical treatments for bacterial infections for more than 100 years. Interest in these viruses is rising again as antibiotic resistance becomes a growing global health threat. Despite this renewed attention, most phage-based research has remained focused on naturally occurring viruses, largely because traditional methods for modifying phages are slow, complex, and difficult to scale.

In a new PNAS study, scientists from New England Biolabs (NEB®) and Yale University report the first fully synthetic system for engineering bacteriophages that target Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a highly antibiotic-resistant bacterium that poses a serious worldwide risk. The approach relies on NEB’s High-Complexity Golden Gate Assembly (HC-GGA) platform, which allows researchers to design and build phages using digital DNA sequence data instead of relying on existing virus samples.

Using this system, the team constructed a P. aeruginosa phage from 28 synthetic DNA fragments. They then programmed the virus with new capabilities by introducing point mutations as well as DNA insertions and deletions. These changes allowed the researchers to swap tail fiber genes to change which bacteria the phage could infect and to add fluorescent markers that made infections visible in real time.

“Even in the best of cases, bacteriophage engineering has been extremely labor-intensive. Researchers spent entire careers developing processes to engineer specific model bacteriophages in host bacteria,” reflects Andy Sikkema, the paper’s co-first author and Research Scientist at NEB. “This synthetic method offers technological leaps in simplicity, safety and speed, paving the way for biological discoveries and therapeutic development.”

Building Phages From Digital DNA

With NEB’s Golden Gate Assembly platform, scientists can assemble an entire phage genome outside the cell using synthetic DNA, incorporating all planned genetic changes during construction. Once assembled, the genome is introduced into a safe laboratory strain where it becomes an active bacteriophage.

This strategy avoids many long-standing obstacles in phage research. Traditional approaches depend on maintaining physical phage samples and using specialized host bacteria, which can be especially challenging when working with viruses that infect dangerous human pathogens. The new method also eliminates the need for repeated rounds of screening or step-by-step genetic edits inside living cells.

Why Golden Gate Assembly Makes a Difference

Unlike other DNA assembly techniques that combine fewer but longer fragments, Golden Gate Assembly uses shorter DNA segments. These shorter pieces are easier to produce, less toxic to host cells, and less likely to contain errors. The method also works well with phage genomes that contain repeated sequences or extreme GC content, both of which often complicate DNA assembly.

By simplifying the process and expanding what is technically possible, this approach significantly broadens the potential for developing bacteriophages as targeted therapies against antibiotic-resistant infections.

Collaboration Turns Tools Into Therapies

The development of this rapid synthetic phage engineering system grew out of close collaboration between NEB scientists and bacteriophage researchers at Yale University. NEB researchers had spent years refining Golden Gate Assembly so it could reliably handle large DNA targets made from many fragments. Yale researchers recognized that these tools could unlock new possibilities in phage biology and reached out to explore more ambitious applications.

NEB scientists first optimized the method using a well-studied model virus, Escherichia coli phage T7. From there, collaborative teams expanded the technique to non-model phages that target some of the most antibiotic-resistant bacteria known.

A related study using the same Golden Gate approach to build high-GC content Mycobacterium phages was published in PNAS in November 2025 in collaboration with the Hatfull Lab at the University of Pittsburgh and Ansa Biotechnologies. In another example, researchers from Cornell University partnered with NEB to create synthetically engineered T7 phages that function as biosensors to detect E. coli in drinking water, described in a December 2025 ACS study.

“My lab builds ‘weird hammers’ and then looks for the right nails,” said Greg Lohman, Senior Principal Investigator at NEB and co-author on the study. “In this case, the phage therapy community told us, ‘That’s exactly the hammer we’ve been waiting for.'”