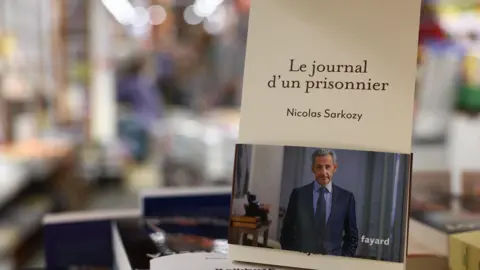

Sarkozy releases prison diaries about his 20 days behind bars

Reuters The former French president wrote about his brief imprisonment for criminal conspiracy Rushed out in under three weeks,

Reuters

ReutersRushed out in under three weeks, Nicolas Sarkozy’s new book “A Prisoner’s Diary” has plenty of colour about what it’s like for a former president to find himself in the isolation wing of a French jail.

We learn that prisoner number 320535 had a 12 square metre cell, equipped with a bed, desk, fridge, shower and television. There was a window, but the view was blocked by a massive plastic panel placed outside.

“It was clean and light enough,” writes Sarkozy. “One could almost have thought one was in a bottom-of-the-range hotel – were it not for the reinforced door with an eye-hole for the prison guards to look through.”

Sarkozy, 70, was released from La Santé prison in Paris last month after serving 20 days of a five-year jail sentence for taking part in an election campaign funding conspiracy. This is his 216-page memoir.

Told he would have to spend 23 hours out of 24 in his room – and that contact with anyone other than a prison employee was forbidden – the former president chose not to take the option of a daily walk in the yard, “more like a cage than a place of promenade”.

Instead he took his daily exercise on a running machine in the tiny sports room, which “became – in my situation – a veritable oasis”.

There is plenty more like this: how he was kept awake on his first night by a neighbour in the isolation wing singing a song from The Lion King and rattling his spoon along the bars of his cell.

How he was “touched by the kindness, delicacy and respect of the prison staff… each one of who addressed me by the title Président”.

And how he was able to cover the walls of his cell with postcards from all the people writing to express their support.

“Touching and sincere, it bore witness to a deep personal bond even though I’d left office so long ago,” he writes.

The details fascinate. Perhaps more consequential are the ruminations on fate, justice and politics.

Sarkozy was sent to jail after a court found him guilty of criminal association for allowing subordinates to try to raise election money 20 years ago from Libya’s Colonel Gaddafi.

At the end of the trial in October, the judge – who could have allowed Sarkozy to remain at liberty pending his appeal – ruled instead that he should go to jail. Three weeks after his incarceration, he was allowed out following a plea from his lawyers.

The former president strongly denies the charges against him, and claims to be the victim of a politically-motivated cabal within the French justice system.

This is all rehearsed again in the book. Indeed at one point Sarkozy compares himself with France’s most famous victim of justice, Alfred Dreyfus – the Jewish officer who was sent to Devil’s Island on a trumped-up espionage charge.

“For any impartial observer who knows their history, the similarities are striking,” he writes.

“The Dreyfus affair originated from fake documents. So did mine… Dreyfus was degraded in front of the troops, when they stripped him of his decorations. I was dismissed from the Legion of Honour, in front of the whole nation.

“And Dreyfus was imprisoned in the Santé – a place which I now know well,” he writes.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesSarkozy’s dismissal from the Legion of Honour – in which as president he had served as Grand Master – is the occasion to settle accounts in the book with France’s current president Emmanuel Macron.

From being a close supporter of Macron, Sarkozy now says he has “turned the page – without going so far as to enter systematic opposition to his politics or person.

“Emmanuel Macron already has too many declared enemies, vilifiers and disappointed friends for me to add to their number.”

Sarkozy’s beef is that Macron never had the “courage” to call him in person to explain why he was being discharged from the Legion. “Had he telephoned, I would have understood his arguments and accepted the decision,” he writes. “Not doing it showed his motives were at the very least insincere.”

But it is Sarkozy’s relations with another political leader – Marine Le Pen – which have attracted most attention in France among reviewers of the book. This is because of the unwonted affection that the former president displays to his one-time arch-rival.

“I appreciated the public declarations she made following my conviction, which were brave and totally unambiguous,” he writes.

Sarkozy telephoned to thank her and he says they had a friendly conversation, at the end of which he undertook not to be party to any future “Republican Front” designed to keep her National Rally from winning an election.

Later he goes on: “Many voters [for the RN] today were supporters of me when I was politically active… Insulting the leaders of the RN is to insult their voters, that is to say people who are potentially our voters.

“I have a lot of differences with the leaders of the RN… But to exclude them from the Republican fold would be a mistake.”

Such accolades from the mainstream are rare for Marine Le Pen and her young co-leader Jordan Bardella.

Coming from a former president who still wields much influence among the traditional French right, the words are like political gold dust.