Psychiatry has finally found an objective way to spot mental illness

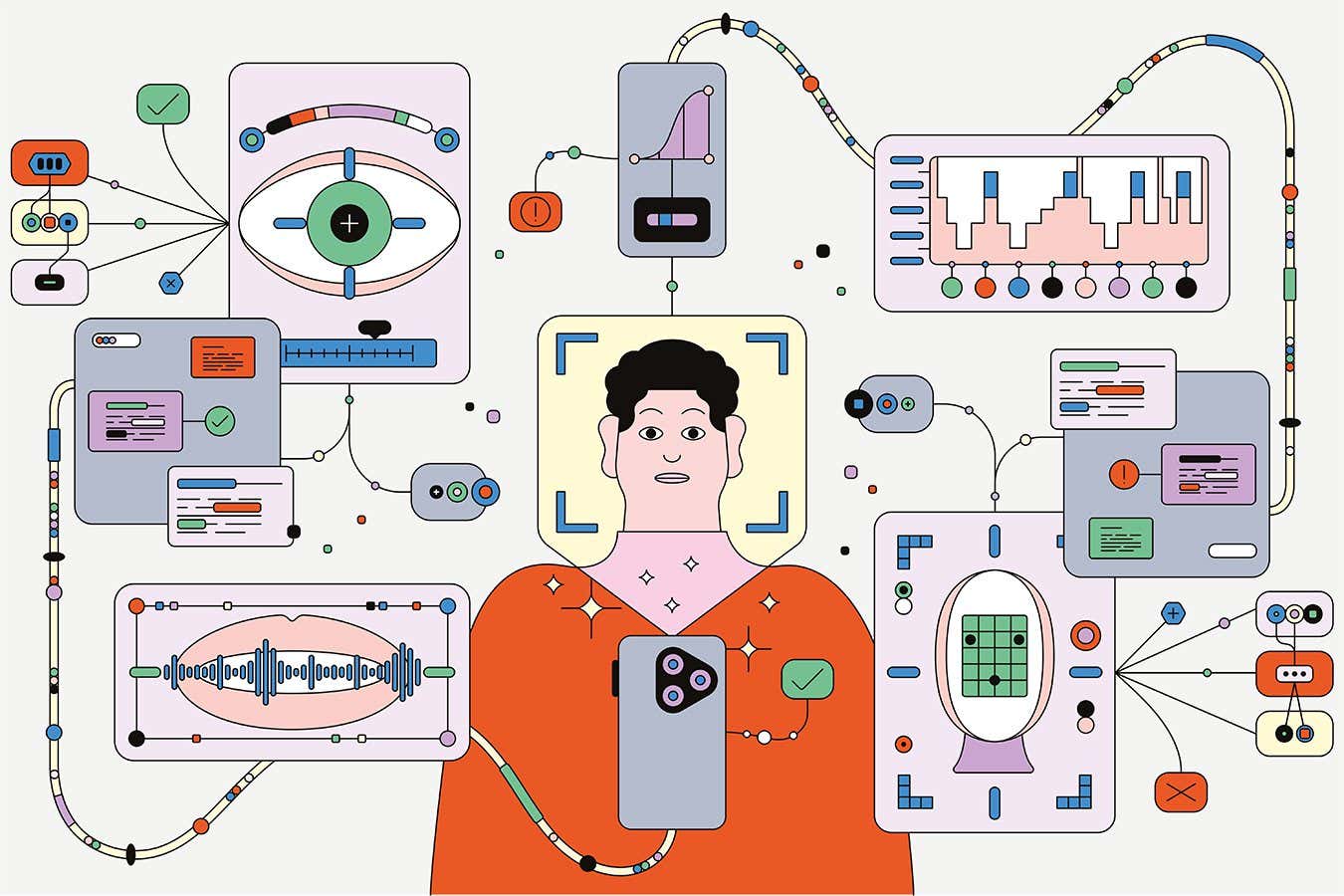

AI is able to bring together dozens of small physical details to help diagnose mental illness Bratislav Milenković “It

AI is able to bring together dozens of small physical details to help diagnose mental illness

Bratislav Milenković

“It seems like this past week has been quite challenging for you,” a disembodied voice tells me, before proceeding to ask a series of increasingly personal questions. “Have you been feeling down or depressed?” “Can you describe what this feeling has been like for you?” “Does the feeling lift at all when something good happens?”

When I respond to each one, my chatbot interviewer thanks me for my honesty and empathises with any issues. By the end of the conversation, I will have also spoken about my sleep patterns, sex drive and appetite for food.

Could this be the future? According to some psychiatrists, chatbots like this may one day play a major role in the diagnostic toolkit. Their aim is to establish a series of “digital biomarkers”, analysed by AI, that will help assess people’s current condition, inform treatment options and keep track of their mental health. The list of candidate biomarkers so far includes the cadences of our voice, flickers of our facial expression, alterations in bodily movements and changes in heart rate that accompany sleep.

Much of the necessary data is already available on the devices that we carry with us every day, providing psychiatrists with an unprecedented view of someone’s life. If it works, it should help to build more personalised treatment plans and pre-empt relapses before someone falls into a crisis. Yet there are also some major questions about the reliability of these diagnoses, not to mention the inevitable privacy concerns.

“These wearables allow you to capture extensive information in real time when people are going about living their life,” says Anissa Abi-Dargham, a psychiatrist and researcher who is based at Stony Brook University in New York state. “It’s limitless, but it comes with the challenge of how to deal with all this data.”

Evolution of psychiatry

If digital biomarkers do come of age, they will mark one of the biggest shifts in psychiatry’s history. Since the earliest days of the field, diagnosis has been based almost entirely on in-depth conversations between doctors and patients. These consultations tend to explore whether someone is experiencing a cluster of symptoms associated with the condition. Depression, for instance, typically involves changes in mood, appetite, sex drive, motivation and sleep.

The collection of symptoms ascribed to each mental health condition can be frustratingly imprecise. There are so many possible presentations of depression, for example – with signs including sleeping both too much and too little – that two people with no overlapping symptoms can be handed the same diagnosis. Meanwhile, the onset of depressive traits could be straightforward unipolar depression, or it could be the start of something more complex like bipolar disorder. Psychiatry has long tried to mimic the diagnostic precision seen elsewhere in medicine, and has always fallen short.

By the middle of the 20th century, scientists began to wonder if they could establish more objective methods through biological markers, or biomarkers, of the different conditions. These included changes in neurotransmitters such as serotonin and dopamine, which may influence the brain’s ability to manage its mood, or hormones, which may be a signal of stress responses gone awry. These biomarkers could be identified through brain imaging, samples of cerebrospinal fluid or simple blood tests.

“

I don’t think we moved the needle in reducing suicide, reducing hospitalisations, improving recovery

“

As psychiatry worked to establish itself as a respectable medical field, the top echelons of researchers devoted themselves to uncovering objective biomarkers. Thomas Insel, who led the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) in the US from 2002 to 2015, pushed the agency to find genetic or neurobiological signatures for mental illnesses. NIMH spent around $20 billion during his tenure, he said in 2017, and fell short: “I don’t think we moved the needle in reducing suicide, reducing hospitalizations, improving recovery for the tens of millions of people who have mental illness.”

The hunt is ongoing. There has been considerable excitement, for example, at the suggestion that certain people with depression show high levels of bodily inflammation, which may allow doctors to use anti-inflammatory drugs. But we aren’t there yet. Currently, there are no accepted biomarkers for any mental health conditions.

Small facial cues can provide insight into conditions like anxiety and depression

A digital transition

This relatively slow progress hasn’t discouraged researchers from attempting to assess mental health based on our digital footprints. According to Shai Mulinari, a sociologist at Lund University in Sweden, the concept developed slowly until the mid-2010s, as we became increasingly dependent on our smartphones and watches, and recent advances in AI have only turbocharged this interest. “Our capacity to analyse big datasets with artificial intelligence has developed very rapidly in the last couple of years.”

So far, this research has identified potential biomarkers for depression, generalised anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, suicidality and post-traumatic stress disorder. These are some of the most common conditions, affecting millions of people, and if digital biomarkers are rolled out effectively, they have the potential to create far more precise treatment monitoring.

Given its sheer prevalence, affecting around 1 in 6 people over their lifetime, depression has attracted the most research. As early as 2009, a team led by Jeffrey Cohn at the University of Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania noted that people with depression tend to have flatter voices that lack much variation in pitch. Using solely this measure, the researchers could predict someone’s mental state according to the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale with an accuracy of 79 per cent. The same was true of facial expressions: a computer program trained to analyse those movements could predict someone’s clinical diagnosis with precisely the same accuracy as the vocal biomarker. Later research suggested it may be possible to identify the stages of bipolar disorder based on vocal pitch, as it tends to rise during manic episodes.

Cohn would go on to found Deliberate AI, where he is now chief scientist, to build on these results and many more. The company has looked into the overall flow of words in conversation, for instance. “Depression is often associated with an increased pause rate and reduced speech rate,” says Marc Aafjes, co-founder and CEO of the company. The facial analyses, meanwhile, now incorporate head movements and muscle dynamics, as well as the more obvious changes in expression, such as how often people smile.

“It is the fusion of these features that allows us to reach high levels of accuracy and reliability,” says Aafjes. “In cases of severe depression, non-verbal behaviours are often the most informative signals – aspects one might miss by analysing voice and speech alone.”

Working with scientists at the Baylor College of Medicine in Texas, Deliberate AI is investigating how biomarkers change during recovery. “We’ve shown high concurrent validity with existing measures, which is very important for acceptability by regulators and clinicians,” says Aafjes.

A new way to diagnose

These advances are allowing digital biomarkers to move from theory to practice. One of Deliberate AI’s tools was recently included in a new pilot programme for the US Food and Drug Administration, where its diagnoses may soon qualify as an endpoint for clinical trials.

And the company is working to streamline the digital diagnostic process, hoping to improve accessibility. At first, it relied on a full clinical interview with a psychiatrist to collect biomarkers. But it can now achieve the same accuracy with just a short snippet of a few minutes of speech.

This may be especially relevant when it is combined with the AI chatbot that I road-tested. The conversation was a little stilted, and I sometimes felt a bit self-conscious spilling my heart to an inhuman entity. It was, however, a mostly seamless experience.

The hope is that these virtual encounters could overcome some of the current barriers to diagnosis, which is limited by the cost and availability of trained professionals to conduct the interviews.

Thanks to that accessibility, it would also be easier to track how someone’s symptoms are changing over time, without having to attend costly appointments or fill out lengthy questionnaires. A person could do short daily check-ins with the AI interviewer, while the software analyses their vocal and facial biomarkers.

“We could use these high-fidelity snapshots to pick up fluctuations in symptoms, in a way that we haven’t been able to do before,” says Aafjes.

The practical applications are serious. By establishing someone’s baseline and then tracking symptoms closely, a psychiatrist could establish whether a treatment like an SSRI drug was working as hoped and then change the dose or medication as necessary.

Data from wearables such as smartwatches can provide key insights into mental health

Balancing biomarkers

The team is also putting together a paper on predicting suicidal thoughts and behaviour using these biomarkers, which could raise the alarm and prompt extra support before someone hurts themselves. “The strongest predictors of ideation included an unnatural consistency in speaking rate and sentence structure,” says Aafjes. “In contrast, the behaviours that were more indicative of direct intent tended to be the volatility in facial expression, specifically in terms of scrunching their eyebrows or smiling sporadically.” If the platform detects that someone is at risk, it could put them in touch with a human psychiatrist for support.

Deliberate AI is by no means alone in this approach; indeed, we may be witnessing something of a gold rush as multiple organisations look to bring AI to psychiatry. The San Francisco-based company Ellipsis Health, for instance, has been developing its own vocal and linguistic biomarkers for depression and generalised anxiety disorder using machine learning. During one trial, published in 2022, users of the company’s app were encouraged to give 5-minute voice samples each week for six weeks, in which they spoke about topics ranging from general health concerns to the state of their life or their work.

The analyses were generally very effective at differentiating between people who did and did not meet the threshold for clinical diagnosis for the two conditions according to standard questionnaires, with low rates of both false negatives and false positives. That is exactly the kind of balance required for a feasible biomarker.

Other candidate biomarkers include measures of bodily movement measured through wearable devices’ accelerometers. Nicholas Jacobson at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire has found that generalised anxiety disorder can be characterised by lower levels of intense activity – indicating physical exercise – combined with higher levels of physical agitation, such as fidgeting or pacing.

Social anxiety disorder, meanwhile, may be evident in people’s phone activity, including how often they contact or are contacted by other people, and whether they answer their phones when they ring. Combining this with motion data, Jacobson found, could accurately predict the severity of people’s symptoms.

The hunt for digital biomarkers has also yielded some surprising disappointments – failures that should sound a note of caution for anyone who believes that technology can replace face-to-face interactions. Consider a study examining people’s sleep quality. Poor sleep is both a cause and a symptom of depression, and so you might expect that accurately monitoring people’s slumber would be a smart way of predicting changes in their mental health.

But Samir Akre, a researcher in medical informatics at the University of California, Los Angeles, found that participants’ self-reported questionnaires about sleep were far more accurate at predicting their depression than data collected from their smartphones and smartwatches.

“

I worry that, at a dystopian level, someone’s watch will say they’re fine even when they are not

“

Akre’s finding highlights the importance of communicating directly with people and listening to their views. For this reason, he cautions psychiatrists not to rely too heavily on digital biomarkers. “At the end of the day, what matters is an individual’s lived experience,” he says. “I worry that, at a dystopian level, someone’s watch will say they’re fine even when they are not, and so no one will listen to them.”

Thankfully, we are still some distance from that bleak future, and the field is developing cautiously. The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has only just started to discuss the next edition of its “bible”, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. At the APA’s annual meeting in June 2025, the organisation announced the introduction of a subcommittee devoted to biomarkers, and it is now calling for researchers to submit their candidate tests.

The subcommittee is planning a careful approach. Should any measure pass its stringent criteria, it will be listed as an “emerging” biomarker. The aim will be to provide a snapshot of the future, rather than endorsing the technologies as definitive diagnostic tests. “We just want them to be informed of what’s happening in the field, and to be able also to evaluate readiness as things become more established,” says subcommittee member Abi-Dargham. “The way this information will be brought up will be very tentative.” Eventually, some of those candidates may be validated, and moved to the category of “established digital technology”, she says. “But that’s a big process.” If that were to occur, it would be a hugely important stamp of approval for psychiatrists to start using the biomarker.

The privacy of people’s medical records may become a concern for some people, if they worry that their mental health is being monitored by third parties. Abi-Dargham emphasises that the subcommittee’s primary focus, however, will be on reliability and its clinical utility – how much it will improve someone’s healthcare.

Without proof of that, though, we may start to see a backlash. Mulinari, for one, suspects that the potential of digital biomarkers is overexaggerated. He points out that the very definition of the “digital biomarker” is vague, given that some suggested candidates – such as people’s phone records – are simply observations of behaviour, rather than measuring anything meaningful about their underlying biology.

“If you call something a digital biomarker, then you might get funding. But if you just call it a correlate [of the illness], then you don’t get any money,” he says. “So, there’s definitely some hype.”

Mulinari remains optimistic, however, comparing the growing interest to the huge excitement around genetic sequencing at the turn of the millennium. “We were told that it was going to solve all diseases,” he says. The technology failed to live up to some of the more exaggerated expectations, but it is now an important part of medicine – and he hopes the same will be true of our digital biomarkers. “There’s always been this hype around new technologies, and sometimes it has been initially problematic, but it has later resulted in important findings.”

Abi-Dargham takes a similar view. “It is a very challenging area,” she says. “But I think it is very promising.”

Need a listening ear? UK Samaritans: 116123 (samaritans.org); US Suicide & Crisis Lifeline: 988 (988lifeline.org). Visit bit.ly/SuicideHelplines for services in other countries.

Topics: