New moonquake discovery could change NASA’s Moon plans

A recently published study reports that shaking from moonquakes, rather than impacts from meteoroids, was the main force behind

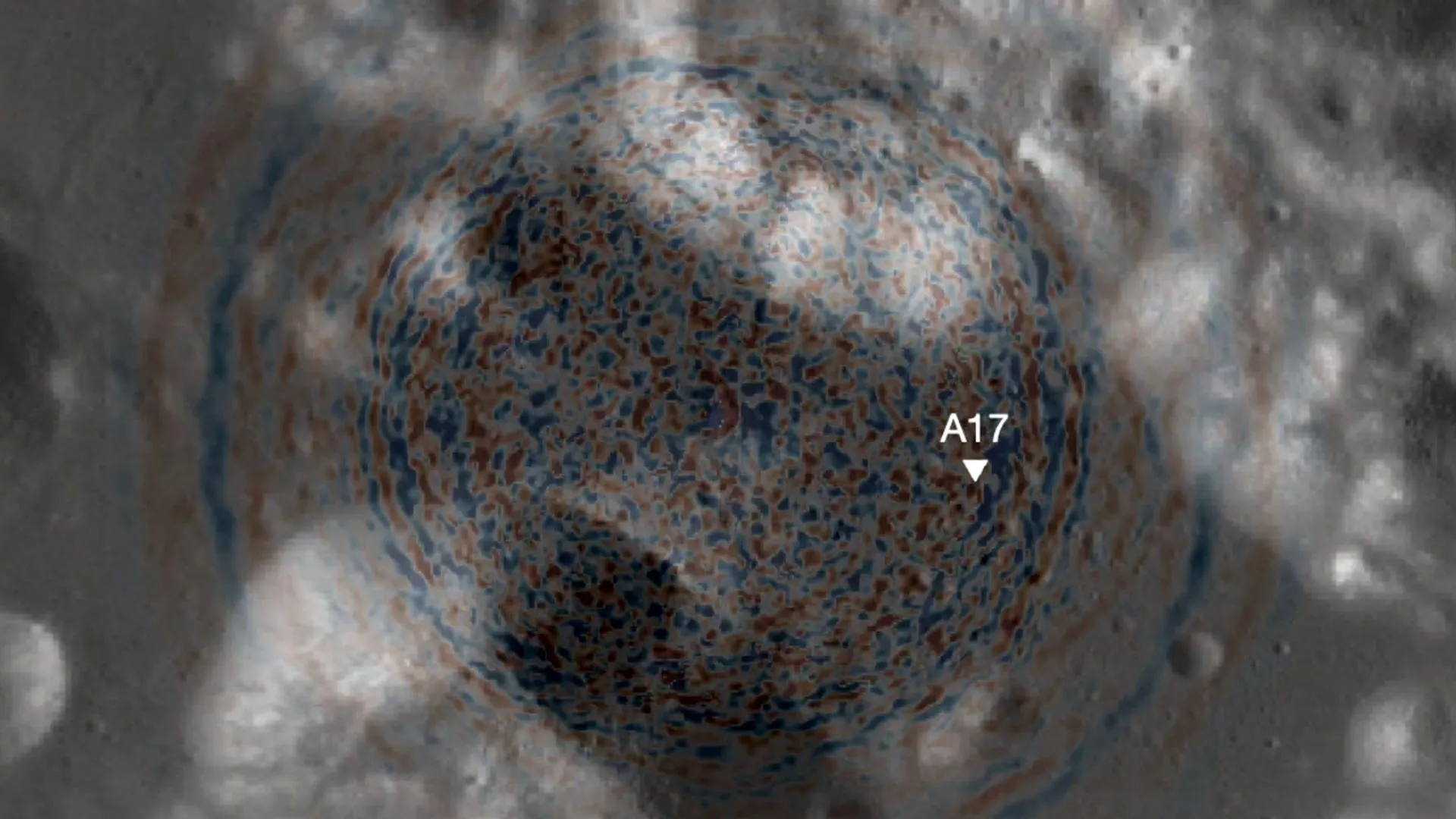

A recently published study reports that shaking from moonquakes, rather than impacts from meteoroids, was the main force behind the shifting terrain in the Taurus-Littrow valley, the site where Apollo 17 astronauts landed in 1972. The researchers also identified a likely explanation for the changing surface features and evaluated potential damage by applying updated models of lunar seismic activity — results that could influence how future missions and long-term settlements are planned on the moon.

The work, conducted by Smithsonian Senior Scientist Emeritus Thomas R. Watters and University of Maryland Associate Professor of Geology Nicholas Schmerr, appeared in the journal Science Advances.

Evidence From Apollo 17 Reveals Ancient Moonquake Activity

To investigate the region, Watters and Schmerr examined samples and observations collected during Apollo 17. Astronauts documented boulder tracks and landslides that appear to have been triggered by moonquakes. By analyzing this geological evidence, the scientists estimated how strong these past quakes were and identified the most likely fault responsible for generating them.

“We don’t have the sort of strong motion instruments that can measure seismic activity on the moon like we do on Earth, so we had to look for other ways to evaluate how much ground motion there may have been, like boulder falls and landslides that get mobilized by these seismic events,” Schmerr said.

Active Lunar Fault May Still Be Producing Quakes

According to the study, moonquakes with magnitudes near 3.0 — mild by Earth standards but significant when occurring close to their source — repeatedly shook the area over the last 90 million years. These events were linked to the Lee-Lincoln fault, a tectonic feature that cuts through the valley floor. The pattern of activity points to the possibility that this fault, one of many young thrust faults identified across the moon, has not yet gone dormant.

“The global distribution of young thrust faults like the Lee-Lincoln fault, their potential to be still active and the potential to form new thrust faults from ongoing contraction should be considered when planning the location and assessing stability of permanent outposts on the moon,” Watters said.

Assessing Daily Risk for Future Lunar Operations

Watters and Schmerr also calculated the statistical likelihood of a damaging quake near an active lunar fault. Their estimate suggests a one in 20 million chance of such an event occurring on any given day.

“It doesn’t sound like much, but everything in life is a calculated risk,” Schmerr noted. “The risk of something catastrophic happening isn’t zero, and while it’s small, it’s not something you can completely ignore while planning long-term infrastructure on the lunar surface.”

Short missions like Apollo 17 face little danger due to their limited duration. However, the researchers found that projects involving longer stays would encounter a gradually increasing risk. Upcoming missions using taller lander designs, including the Starship Human Landing System, may be more susceptible to ground acceleration caused by moonquakes close to an active fault. These concerns are particularly important as NASA moves forward with the Artemis program, which aims to maintain a continuous human presence on the moon. Watters and Schmerr stressed that modern missions must account for hazards not encountered during the Apollo era.

“If astronauts are there for a day, they’d just have very bad luck if there was a damaging event,” Schmerr added. “But if you have a habitat or crewed mission up on the moon for a whole decade, that’s 3,650 days times 1 in 20 million, or the risk of a hazardous moonquake becoming about 1 in 5,500. It’s similar to going from the extremely low odds of winning a lottery to much higher odds of being dealt a four of a kind poker hand.”

Advancing the Field of Lunar Paleoseismology

Schmerr views this research as part of a growing field known as lunar paleoseismology, which focuses on ancient seismic activity. Unlike Earth, where scientists can excavate trenches to reveal evidence of past earthquakes, lunar researchers must rely on material already gathered and imaging from orbit. He expects future progress to accelerate thanks to higher resolution mapping, new technology, and upcoming Artemis missions that plan to deploy seismometers far more advanced than those used during Apollo.

“We want to make sure that our exploration of the moon is done safely and that investments are made in a way that’s carefully thought out,” Schmerr said. “The conclusion we came to is: don’t build right on top of a scarp, or recently active fault. The farther away from a scarp, the lesser the hazard.”

Support From the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Mission

This research was supported by NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter mission, which launched on June 18, 2009. LRO is operated by NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center for the Science Mission Directorate. This article does not necessarily reflect the views of this organization.