NASA-JAXA XRISM Finds Elemental Bounty in Supernova Remnant

For the first time, scientists have made a clear X-ray detection of chlorine and potassium in the wreckage of

For the first time, scientists have made a clear X-ray detection of chlorine and potassium in the wreckage of a star using data from the Japan-led XRISM (X-ray Imaging and Spectroscopy Mission) spacecraft.

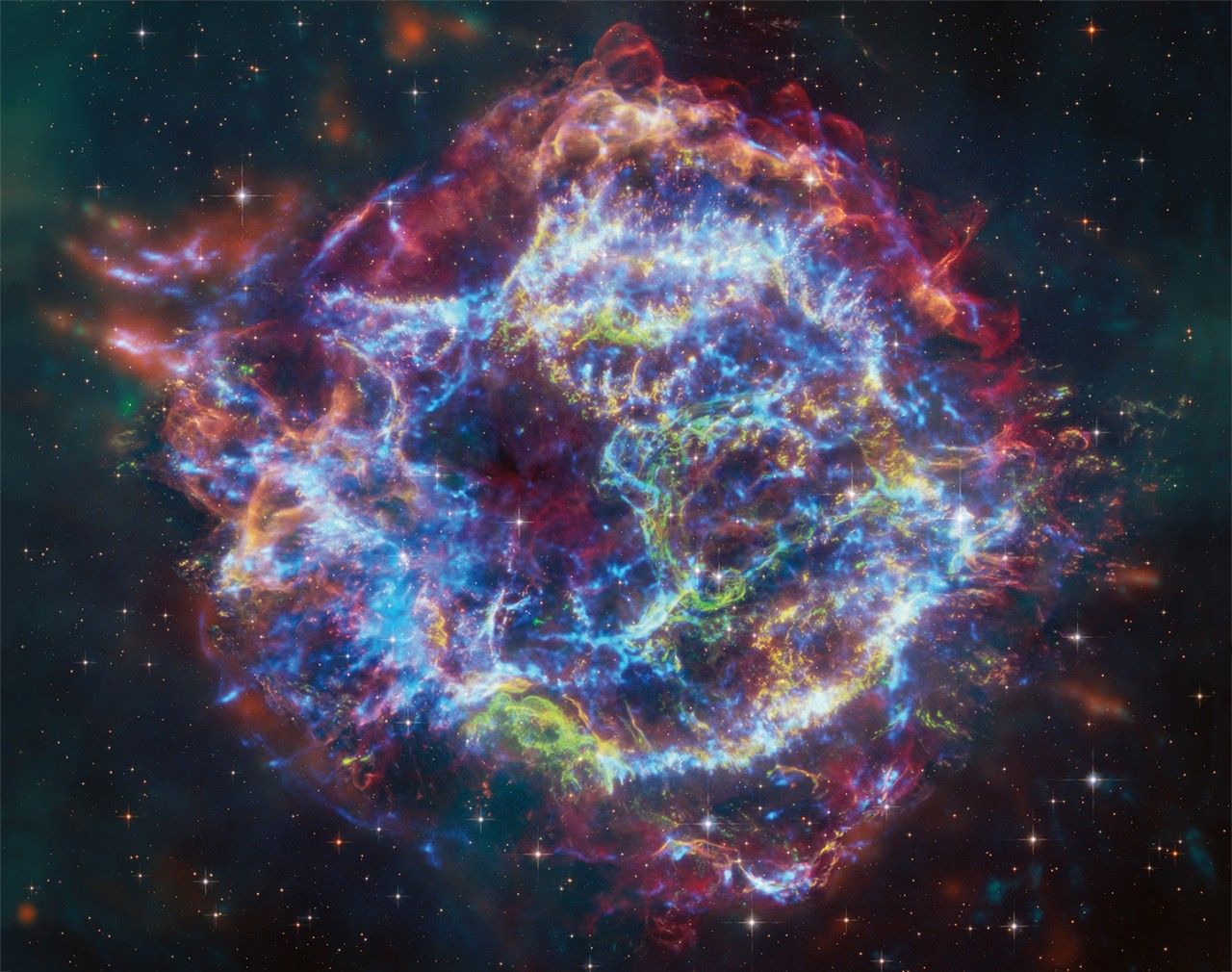

The Resolve instrument aboard XRISM, pronounced “crism,” discovered these elements in a supernova remnant called Cassiopeia A or Cas A, for short. The expanding cloud of debris is located about 11,000 light-years away in the northern constellation Cassiopeia.

“This discovery helps illustrate how the deaths of stars and life on Earth are fundamentally linked,” said Toshiki Sato, an astrophysicist at Meiji University in Tokyo. “Stars appear to shimmer quietly in the night sky, but they actively forge materials that form planets and enable life as we know it. Now, thanks to XRISM, we have a better idea of when and how stars might make crucial, yet harder-to-find, elements.”

A paper about the result published Dec. 4 in Nature Astronomy. Sato led the study with Kai Matsunaga and Hiroyuki Uchida, both at Kyoto University in Japan. JAXA (Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency) leads XRISM in collaboration with NASA, along with contributions from ESA (European Space Agency). NASA and JAXA also codeveloped the Resolve instrument.

Stars produce almost all the elements in the universe heavier than hydrogen and helium through nuclear reactions. Heat and pressure fuse lighter ones, like carbon, into progressively heavier ones, like neon, creating onion-like layers of materials in stellar interiors.

Nuclear reactions also take place during explosive events like supernovae, which occur when stars run out of fuel, collapse, and explode. Elemental abundances and locations in the wreckage can, respectively, tell scientists about the star and its explosion, even after hundreds or thousands of years.

Some elements — like oxygen, carbon, and neon — are more common than others and are easier to detect and trace back to a particular part of the star’s life.

Other elements — like chlorine and potassium — are more elusive. Since scientists have less data about them, it’s more difficult to model where in the star they formed. These rarer elements still play important roles in life on Earth. Potassium, for example, helps the cells and muscles in our bodies function, so astronomers are interested in tracing its cosmic origins.

The roughly circular Cas A supernova remnant spans about 10 light-years, is over 340 years old, and has a superdense neutron star at its center — the remains of the original star’s core. Scientists using NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory had previously identified signatures of iron, silicon, sulfur, and other elements within Cas A.

In the hunt for other elements, the team used the Resolve instrument aboard XRISM to look at the remnant twice in December 2023. The researchers were able to pick out the signatures for chlorine and potassium, determining that the remnant contains ratios much higher than expected. Resolve also detected a possible indication of phosphorous, which was previously discovered in Cas A by infrared missions.

Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

“Resolve’s high resolution and sensitivity make these kinds of measurements possible,” said Brian Williams, the XRISM project scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “Combining XRISM’s capabilities with those of other missions allows scientists to detect and measure these rare elements that are so critical to the formation of life in the universe.”

The astronomers think stellar activity could have disrupted the layers of nuclear fusion inside the star before it exploded. That kind of upheaval might have led to persistent, large-scale churning of material inside the star that created conditions where chlorine and potassium formed in abundance.

The scientists also mapped the Resolve observations onto an image of Cas A captured by Chandra and showed that the elements were concentrated in the southeast and northern parts of the remnant.

This lopsided distribution may mean that the star itself had underlying asymmetries before it exploded, which Chandra data indicated earlier this year in a study Sato led.

“Being able to make measurements with good statistical precision of these rarer elements really helps us understand the nuclear fusion that goes on in stars before and during supernovae,” said co-author Paul Plucinsky, an astrophysicist at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian in Cambridge, Massachusetts. “We suspected a key part might be asymmetry, and now we have more evidence that’s the case. But there’s still a lot we just don’t understand about how stars explode and distribute all these elements across the cosmos.”

By Jeanette Kazmierczak

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

Media Contact:

Claire Andreoli

301-286-1940

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.