Murder victim discovered to have two sets of DNA due to rare condition

Blood at a crime scene that contained a Y chromosome led to a rare discovery Shutterstock/PeopleImages The forensic examination

Blood at a crime scene that contained a Y chromosome led to a rare discovery

Shutterstock/PeopleImages

The forensic examination of a murder victim has revealed that she had chimerism – meaning her body contained cells that were genetically distinct, as if they came from two different individuals.

In this case, the unidentified woman had varying proportions of male and female cells in different tissues. The most likely explanation for this is that she developed from a single egg that was fertilised by two sperm − one carrying an X chromosome and the other a Y, biologists told New Scientist.

“This is a fascinating case but not completely unprecedented,” says David Haig at Harvard University.

There are occasionally visible signs of chimerism, as with the singer Taylor Muhl who has highlighted her chimerism to raise awareness of the condition. More often, however, it is revealed only by genetic testing.

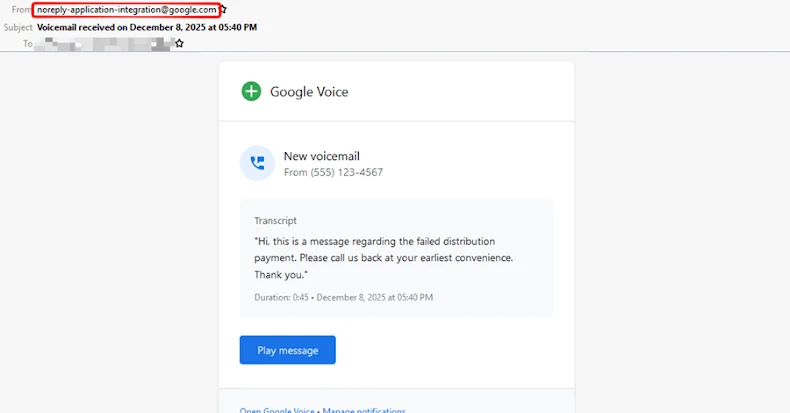

This was the case with the murder victim, who lived in China and was killed by a gunshot. Analysis of blood from the scene revealed the presence of a Y chromosome, so further tests were done.

These revealed differing proportions of female (XX) and male (XY) cells throughout the woman’s body. For instance, in one hair sample, most of the cells were XY, while the kidney contained an equal mix. The other 16 tissues tested were mostly XX, in varying ratios.

Most known cases of XX/XY chimerism have been detected because people have ambiguous sexual characteristics, but in this case the woman’s anatomy gave no indication of her condition and she had a son. She was likely to have been unaware she had chimerism.

One way that XX/XY chimeras can form is when non-identical twins fuse. That is when two eggs are fertilised separately, giving rise to two embryos that would normally become non-identical twins but instead merge together.

However, the murder victim’s X chromosome in her XY cells was identical to one of the X chromosomes in her XX cells. The only way these X chromosomes can be identical is if both came from the same egg, which rules out the fusion of non-identical twins.

It used to be thought that a single egg could divide to form two eggs that would each then be fertilised, forming separate embryos that then fused. This is what the forensic team in China suggests happened.

But this possibility can be ruled out, says Michael Gabbett at the Queensland University of Technology in Brisbane.

“When these types of chimeras were first observed in humans, [this] was the prevailing theory, but no one has subsequently ever been able to demonstrate this can occur in humans or other mammals,” says Gabbett.

Instead, he thinks one egg was fertilised by two sperm, resulting in a fertilised egg with three sets of chromosomes. These sets then replicated, resulting in six sets of chromosomes, and the egg then divided into three.

Two of these cells would have got one set of chromosomes from the egg and the other from a sperm, so both could develop normally. The third cell would have got both sets from sperm, resulting in abnormalities that are likely to have killed off its lineage.

The phenomenon is sometimes called trigametic chimerism, because it involves three gametes – one egg and two sperm. Haig agrees that this is probably what happened.

This phenomenon is extremely rare – and even more rarely the embryo then splits, resulting in the development of semi-identical or sesquizygotic twins – who can also have chimerism. This is so unusual that only two pairs of semi-identical twins are known, one of which Gabbett helped to identify.

In the case of the murder victim, the cells remained together and contributed to all parts of her body in varying degrees. There are a few other known cases of trigametic chimerism, but this is the first time such extensive testing of different organs has been done, according to the team in China.

Another form of chimerism, known as microchimerism, is much more common than trigametic chimerism or the fusion of non-identical twins. It arises during pregnancy when cells from the mother enter the fetus, or cells from the fetus enter the mother, and become part of the other’s body. Younger siblings may even get cells from older siblings, or from aunts and uncles.

Topics: