Microbiome study hints that fibre could be linked to better sleep

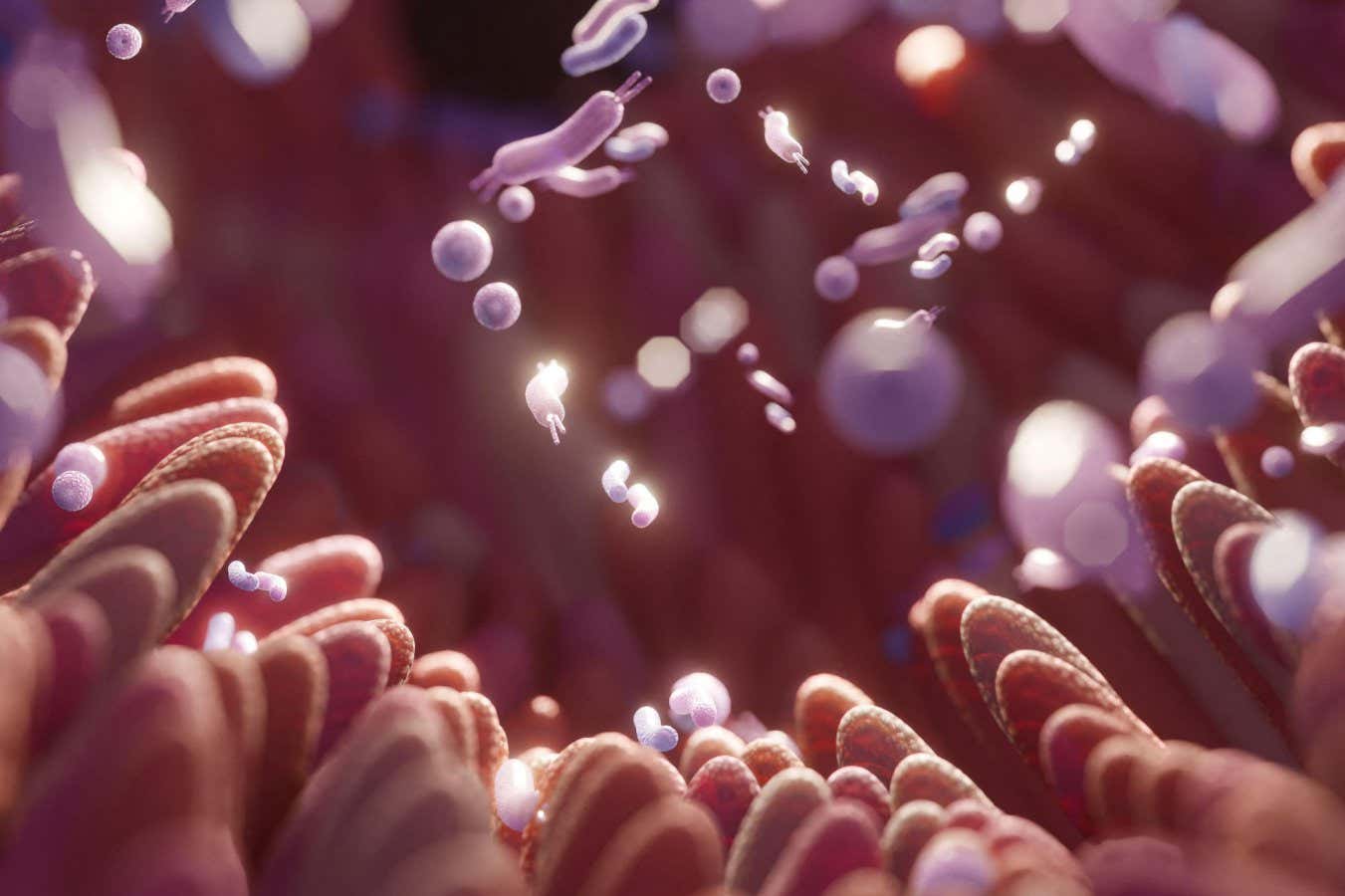

Microbial activity in the gut might affect our quality of sleep Oleksandra Troian / Alamy We know that diet

Microbial activity in the gut might affect our quality of sleep

Oleksandra Troian / Alamy

We know that diet has a role in sleep conditions – and now it seems that dietary fibre in particular might help address them.

Links have previously been found between several sleep conditions and the gut microbiome, especially through a lack of diversity of bacterial species, raising the prospect that eating better might help you sleep better. However, until now, no one has pinpointed specific microbial species – and, in turn, the specific foods that they thrive on – that are consistently involved with sleep quality.

A new systematic review of earlier studies might help plug that gap. Conducted by Zhe Wang at Shandong First Medical University in China and colleagues, it included 53 previous observational studies that compared the gut microbiota of people who experienced sleep disturbances with those of people who didn’t. The studies included a total of 7497 individuals with sleep conditions and 9165 without.

The researchers found that the overall number of different bacterial species – known as alpha diversity – was lower in people with a sleep condition. And in people with insomnia, obstructive sleep apnea or REM sleep behaviour disorder – a condition in which the muscle paralysis typical of REM sleep fails to occur, meaning sleepers physically act out their dreams – there was also a consistent reduction in the relative abundance of anti-inflammatory, butyrate-producing bacteria such as Faecalibacterium, and an increase of pro-inflammatory bacteria like Collinsella.

This suggests that dietary fibre is important, because it is through the fermentation of such foods that Faecalibacterium produces butyrate. The butyrate then serves as an energy source for colon cells, strengthens the gut barrier and reduces inflammation.

They add that the microbial signature could be used as a criterion to help distinguish clinical conditions from other sleep complaints, helping make treatment more targeted.

Katherine Maki at the US National Institutes of Health in Maryland says the work is in line with research her own group has done that is currently under review and has found similar relationships between sleep and butyrate-producing Faecalibacterium.

“Taken together, these converging findings… highlight a plausible microbiome-metabolite pathway linking sleep and host physiology that warrants direct testing in future mechanistic and interventional studies,” says Maki.

“Overall, this meta-analysis supports the idea that Faecalibacterium and insomnia are linked,” says Elizabeth Holzhausen at Michigan State University. “But because these studies are observational, we can’t determine causality.”

She says one possibility is that insomnia affects diet by reducing fibre intake, which could lead to lower levels of Faecalibacterium. Another possibility is that lower levels of Faecalibacterium result in reduced butyrate, which may influence sleep.

To establish whether there is a causal relationship, studies involving controlled interventions will be needed, says Holzhausen.

The results add weight to the importance of the gut microbiome to our sleep health and help shed light on potentially influential shifts in gut microbial signalling pathways that are linked to sleep-affecting processes like hormone release, metabolism and inflammation, says Maki.

If people want to boost their sleep, she says, although it is too soon to be recommending boosting fibre intake for this purpose, there is some evidence as to which dietary aspects can influence sleep.

Avoiding caffeine may help, say Makin, because it can slow down the onset of sleep, especially at higher doses and when ingested later in the day. Alcohol can also disrupt sleep, despite the common belief that it is a sleep aid. What’s more, having meals close to when you go to bed is associated with poorer sleep.

For a bedtime boost, there is some evidence that drinking tart cherry juice has promise, says Maki, and higher overall diet quality with increased fibre intake is frequently associated with better sleep, but which aspects of the diet are influential here, if any, is uncertain.

Topics: