Jellyfish sleep about as much as humans do – and nap like us too

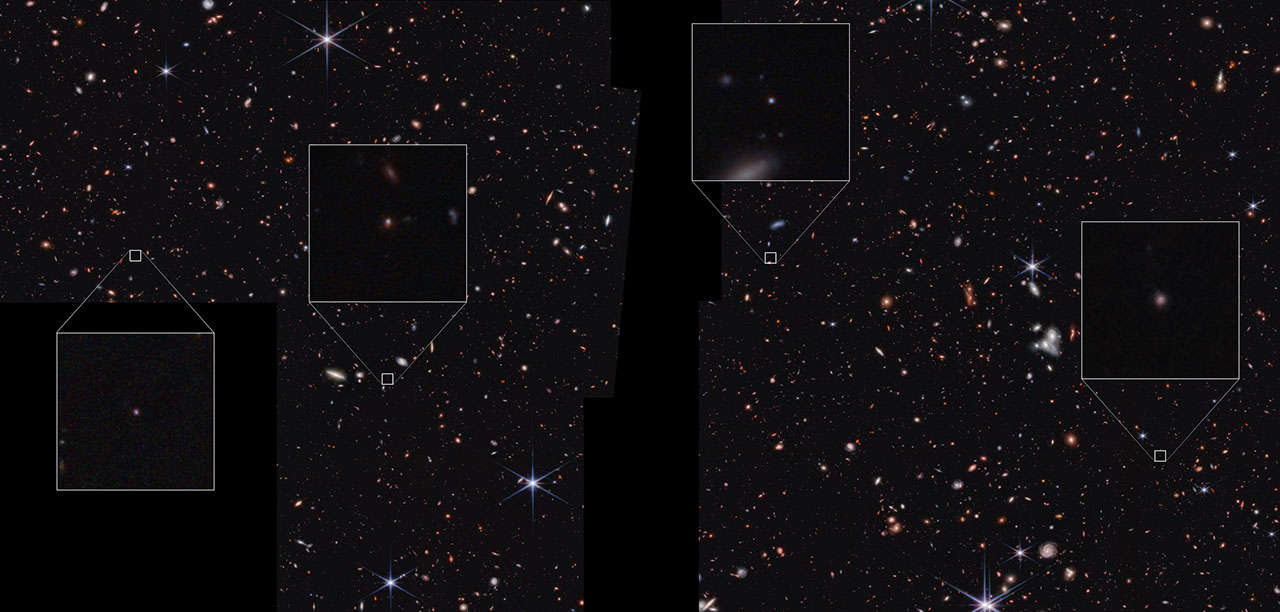

An upside-down jellyfish in its natural habit on the seabed Eilat. Gil Koplovitch Jellyfish seem to sleep for about

An upside-down jellyfish in its natural habit on the seabed

Eilat. Gil Koplovitch

Jellyfish seem to sleep for about 8 hours a day, take midday naps and snooze more after a bad night’s sleep – just like us. Sleep is thought to have first evolved in marine creatures like these, and having a better understanding of their precise sleep patterns may help explain why it came about at all.

“It’s funny: just like humans, they spend about a third of their time asleep,” says Lior Appelbaum at Bar-Ilan University in Ramat Gan, Israel.

In animals with brains, such as mammals, sleep is crucial for things like storing memories and clearing metabolic waste from the brain. But it was unclear why sleep evolved in jellyfish, which belong to a group of brainless animals called cnidarians, in which neurons – arranged in a relatively simple network across the body – are also thought to have first evolved.

Appelbaum and his colleagues used cameras to record Cassiopea andromeda, a species of upside-down jellyfish, in tanks for 24 hours. The jellyfish, which usually sit tentacles-up in shallow waters on the seabed, were exposed to light half the time to simulate day and night.

The team found that during the simulated daylight, C. andromeda individuals pulsed their bell-shaped bodies more than 37 times per minute, on average, and rapidly responded to sudden bright light or food, suggesting they were awake. In contrast, at night, they pulsed less often and took longer to respond to the light or food, indicating they were asleep. Such pulsing is thought to help the animals feed and spread oxygen throughout their bodies, says Appelbaum.

Overall, the jellyfish slept for about 8 hours, mostly at night, with a short midday nap lasting roughly 1 to 2 hours. Prior studies had already shown that C. andromeda sleeps at night, but until now its exact sleep patterns were unclear, he says.

In another experiment where the researchers pulsed water at the jellyfish to disrupt their sleep, the animals slept more the next day. “This is like us: if we’re sleep deprived during the night, we sleep during the day because we’re tired,” says Appelbaum.

Crucially, further analysis revealed that DNA damage accumulates in C. andromeda’s neurons while it is awake, but sleep seems to reduce this damage, which would otherwise degrade and impair neurons, he says. Supporting this idea, when the team used ultraviolet light to dial up DNA damage, the jellyfish slept more.

Further research is needed to see if the same occurs in other jellyfish species, or even mammals, but the researchers saw similar results when they repeated the experiments in the starlet sea anemone (Nematostella vectensis) – providing the first evidence that sea anemones sleep, says Appelbaum.

Topics: