Inside the mysterious collapse of dark matter halos

For nearly 100 years, dark matter has remained one of the biggest unanswered questions in cosmology. Although it cannot

For nearly 100 years, dark matter has remained one of the biggest unanswered questions in cosmology. Although it cannot be seen directly, its gravitational influence shapes galaxies and the large-scale structure of the universe. At the Perimeter Institute, two physicists are investigating how a particular form of dark matter, known as self-interacting dark matter (SIDM), may influence the way cosmic structures grow and change over time.

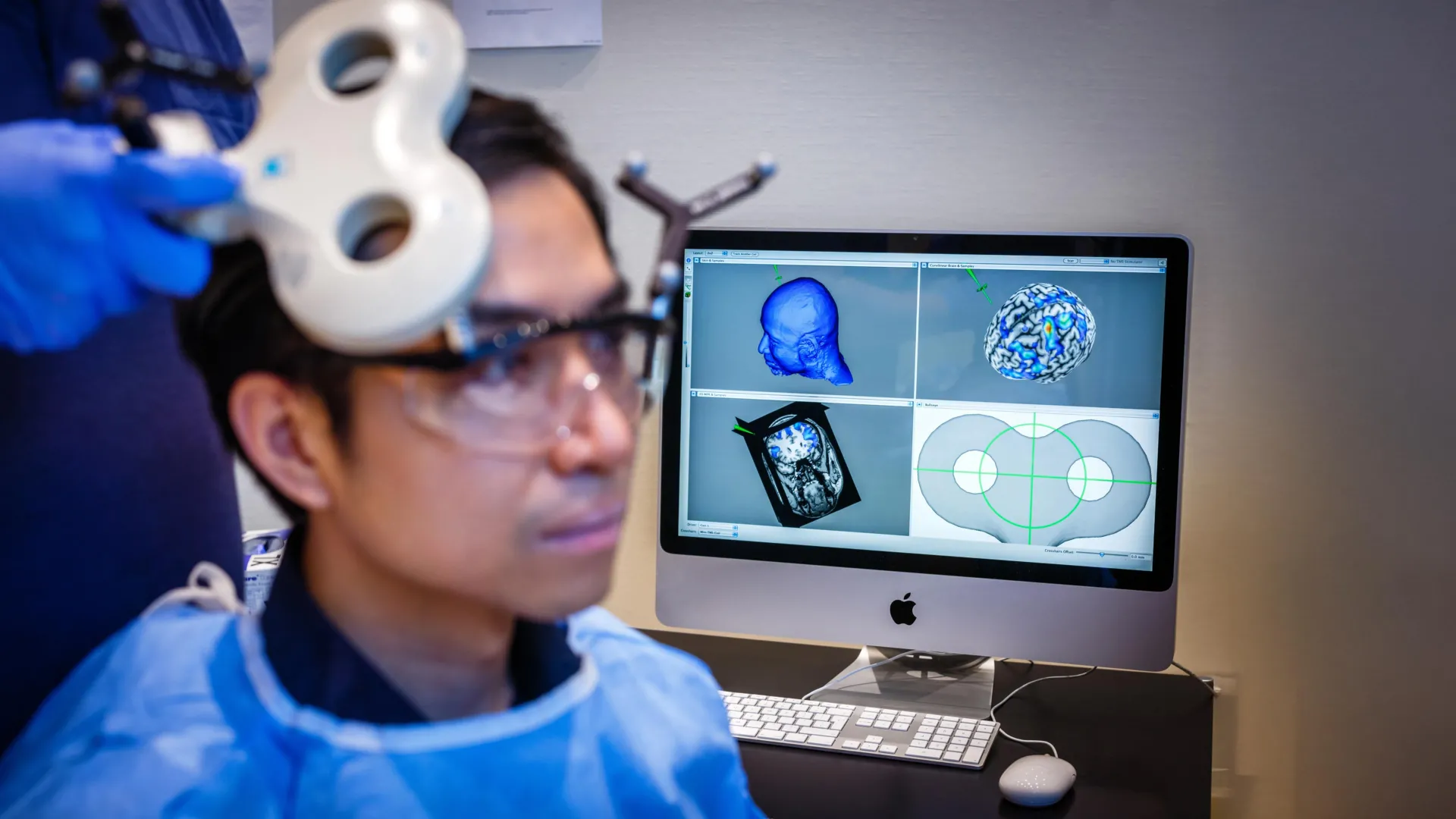

In research published in Physical Review Letters, James Gurian and Simon May introduce a new computational tool designed to study how SIDM affects galaxy formation. Their approach makes it possible to explore types of particle interactions that were previously difficult or impractical to model accurately.

When Dark Matter Interacts With Itself

SIDM is a theoretical form of dark matter whose particles can collide with one another but do not interact with baryonic matter, the familiar matter made of protons, neutrons, and electrons. These collisions conserve energy through what physicists call elastic self-interactions. This behavior can strongly influence dark matter halos, the massive concentrations of dark matter that surround galaxies and help guide their evolution.

“Dark matter forms relatively diffuse clumps which are still much denser than the average density of the universe,” says Gurian, a Perimeter postdoctoral fellow and co-author of the study. “The Milky Way and other galaxies live in these dark matter halos.”

Heat, Energy Flow, and Core Collapse

The self-interacting nature of SIDM can trigger a process known as gravothermal collapse within dark matter halos. This phenomenon arises from a counterintuitive property of gravity, where systems bound by gravity become hotter as they lose energy rather than cooling down.

“You have this self-interacting dark matter which transports energy, and it tends to transport energy outwards in these halos,” says Gurian. “This leads to the inner core getting really hot and dense as energy is transported outwards.” Over time, this process can drive the core of the halo toward a dramatic collapse.

A Missing Link in Dark Matter Modeling

Simulating the structures formed by SIDM has long been a challenge. Existing methods work well only under certain conditions. Some simulations perform best when dark matter is sparse and collisions are rare, while others are effective only when dark matter is extremely dense and interactions are frequent.

“One approach is an N-body simulation approach that works really well when dark matter is not very dense and collisions are infrequent. The other approach is a fluid approach — and this works when dark matter is very dense and collisions are frequent.”

“But for the in-between, there wasn’t a good method,” Gurian says. “You need an intermediate range approach to correctly go between the low-density and high-density parts. That was the origin of this project.”

A Faster and More Accessible Simulation Tool

To solve this problem, Gurian and his co-author Simon May, a former Perimeter postdoctoral researcher now serving as an ERC Preparative Fellow at Bielefeld University, developed a new code called KISS-SIDM. The software bridges the gap between existing simulation methods, delivering higher accuracy while requiring far less computing power. It is also publicly available for other researchers.

“Before, if you wanted to check different parameters for self-interacting dark matter, you needed to either use this really simplified fluid model, or go to a cluster, which is computationally expensive. This code is faster, and you can run it on your laptop,” says Gurian.

Opening the Door to New Dark Matter Physics

Interest in interacting dark matter has grown in recent years, partly due to puzzling features seen in galaxies that may not fit standard models.

“There has been considerable interest recently in interacting dark matter models, due to possible anomalies detected in observations of galaxies that may require new physics in the dark sector,” says Neal Dalal, a member of the Perimeter Institute research faculty.

“Previously, it was not possible to perform accurate calculations of cosmic structure formation in these sorts of models, but the method developed by James and Simon provides a solution that finally allows us to simulate the evolution of dark matter in models with significant interactions,” Dalal says. “Their paper should enable a broad spectrum of studies that previously were intractable.”

Implications for Black Holes and Beyond

The collapse of dark matter cores is especially intriguing because it may leave observable signatures, including possible connections to black hole formation. However, how this process ultimately ends remains an open question.

“The fundamental question is, what’s the final endpoint of this collapse? That’s what we’d really like to do — study the phase after you form a black hole.”

By making it possible to explore these extreme conditions in detail, the new code represents an important step toward answering some of the deepest questions about dark matter and the structure of the universe.