Hybrid megapests evolving in Brazil are threat to crops worldwide

A corn earworm (Helicoverpa zea) larva feeding on a cotton plant Debra Ferguson/Design Pics Editorial/Universal Images Group via Getty

A corn earworm (Helicoverpa zea) larva feeding on a cotton plant

Debra Ferguson/Design Pics Editorial/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Two “megapests” that are already a major problem for farmers worldwide, the cotton bollworm and the corn earworm, have interbred in Brazil and swapped genes conferring resistance to pesticides. The hybrid strains that are evolving could devastate soya and other crops in Brazil and around the world if they can’t be controlled, threatening global food security.

“It has the potential to be an enormous problem,” says Chris Jiggins at the University of Cambridge.

In particular, many countries import soya from Brazil to feed both people and animals. “It kind of feeds the world,” says Jiggins.

More than 90 per cent of the soya grown in Brazil is genetically modified Bt soya containing a built-in pesticide. If yields fall due to pests becoming resistant, it would lead to yet more increases in the price of many foods. It could also increase deforestation and greenhouse gas emissions, as farmers compensate by clearing more farmland.

The corn earworm (Helicoverpa zea) is a moth native to the Americas whose caterpillars eat most parts of plants. They are particularly damaging to corn, but also feed on many other plants including tomatoes, potatoes, cucumbers and aubergines (eggplants).

In Brazil, H. zea wasn’t a major problem for farmers growing soya because it tends not to feed on the crop. But then, in 2013, the cotton bollworm (Helicoverpa armigera) was detected in Brazil. H. armigera is a relative of H. zea that is widespread across Eurasia. The two moths have been described as megapests because they are so damaging and hard to combat.

“They are pretty exceptional pests, so I think that’s justified,” says Jiggins. “Controlling the movement of the moths is almost impossible. They move very large distances.”

H. armigera also feeds on a wide range of plants and, unlike H. zea, it thrives on soya, so it caused huge problems for farmers when it reached Brazil. “It was billions of dollars of cost to Brazilian agriculture,” says Jiggins.

This was largely solved by the introduction of Bt soya, which is genetically modified to produce a protein made by the soil bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis that is toxic to most insects.

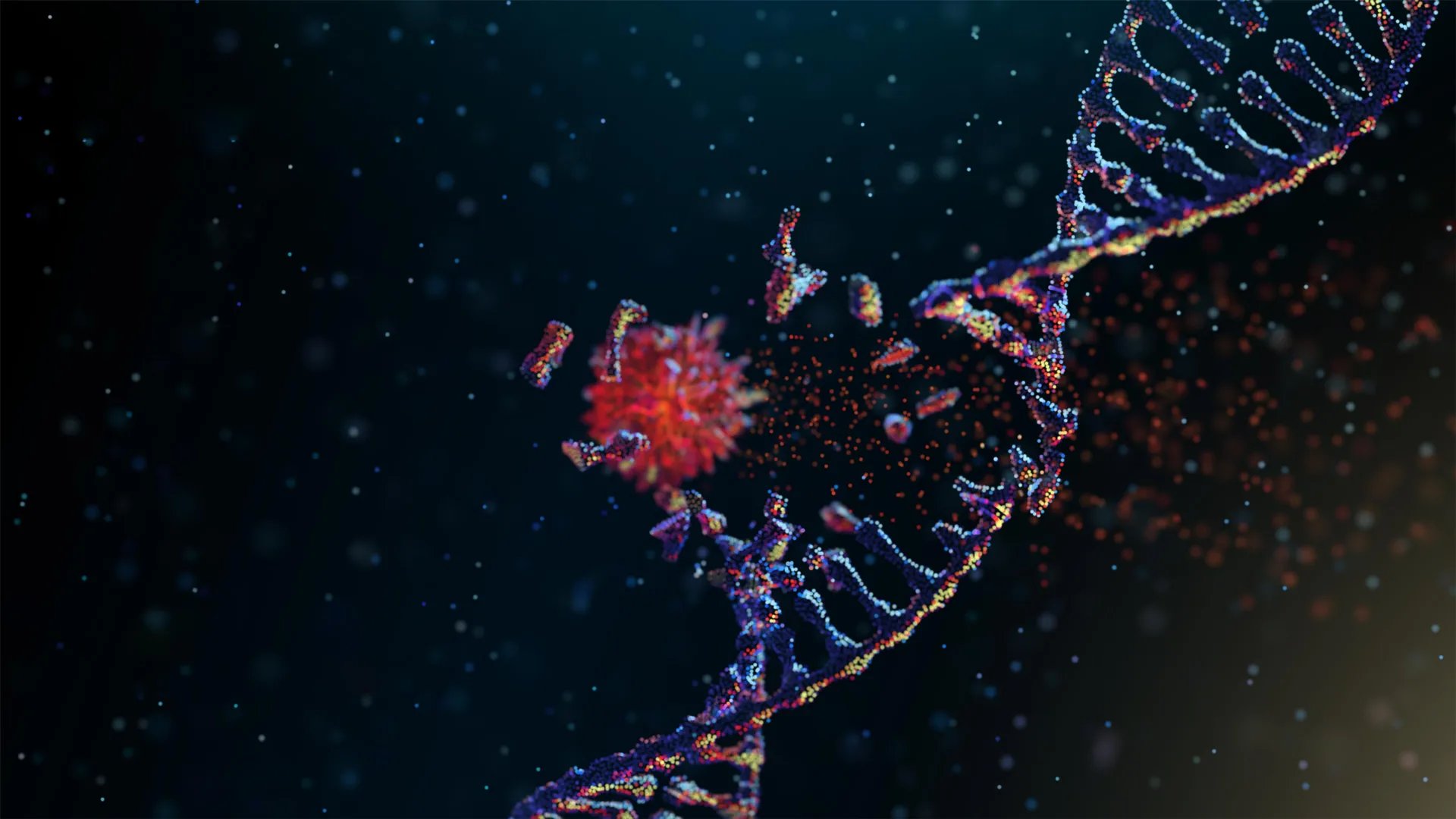

It was thought that H. armigera and H. zea couldn’t interbreed, but in 2018 genetic analysis revealed a few hybrids between the species. Jiggins and his colleagues have now analysed the genome of nearly 1000 moths collected in Brazil over the past decade.

They found that a third of H. armigera now carry genes providing resistance to the Bt toxin – and they got these genes from H. zea. Bt maize was first introduced in North America in the 1990s, where some H. zea strains evolved resistance. These resistance genes seem to have spread to South America and now crossed species. As yet, the hybrid H. armigera haven’t been a major problem, says Jiggins, but that could change as resistance spreads.

The transfer has gone both ways – nearly all H. zea in Brazil now have a gene conferring resistance to a class of insecticides called pyrethroids that was acquired from H. armigera. “We’re just sort of blown away by how rapidly it’s happened,” says Jiggins.

“With global connectivity and climate change together lowering barriers to species’ range expansions, such megapests are likely to be an increasing global problem, as is the escalating rate of biological invasions more generally,” says Angela McGaughran at the University of Waikato in New Zealand.

Farmers are supposed to plant non-Bt crops alongside Bt ones to create refuges that slow the spread of resistant pests. However, in many countries, these guidelines aren’t followed.

Plant companies are introducing new strains of Bt crops that produce two, three or even five different Bt proteins to combat resistance. “But bringing such new products to market is expensive and slow, so it is best to sustain the efficacy of current Bt proteins with resistance-management tactics, including refuges from exposure to Bt crops,” says Bruce Tabashnik at the University of Arizona.

While hybridisation can spread resistance, Tabashnik says the main issue is evolution within species. In China, strains of H. armigera have independently evolved resistance to the original Bt toxin, he says.

Topics: