Huge fossil bonanza preserves 512-million-year-old ecosystem

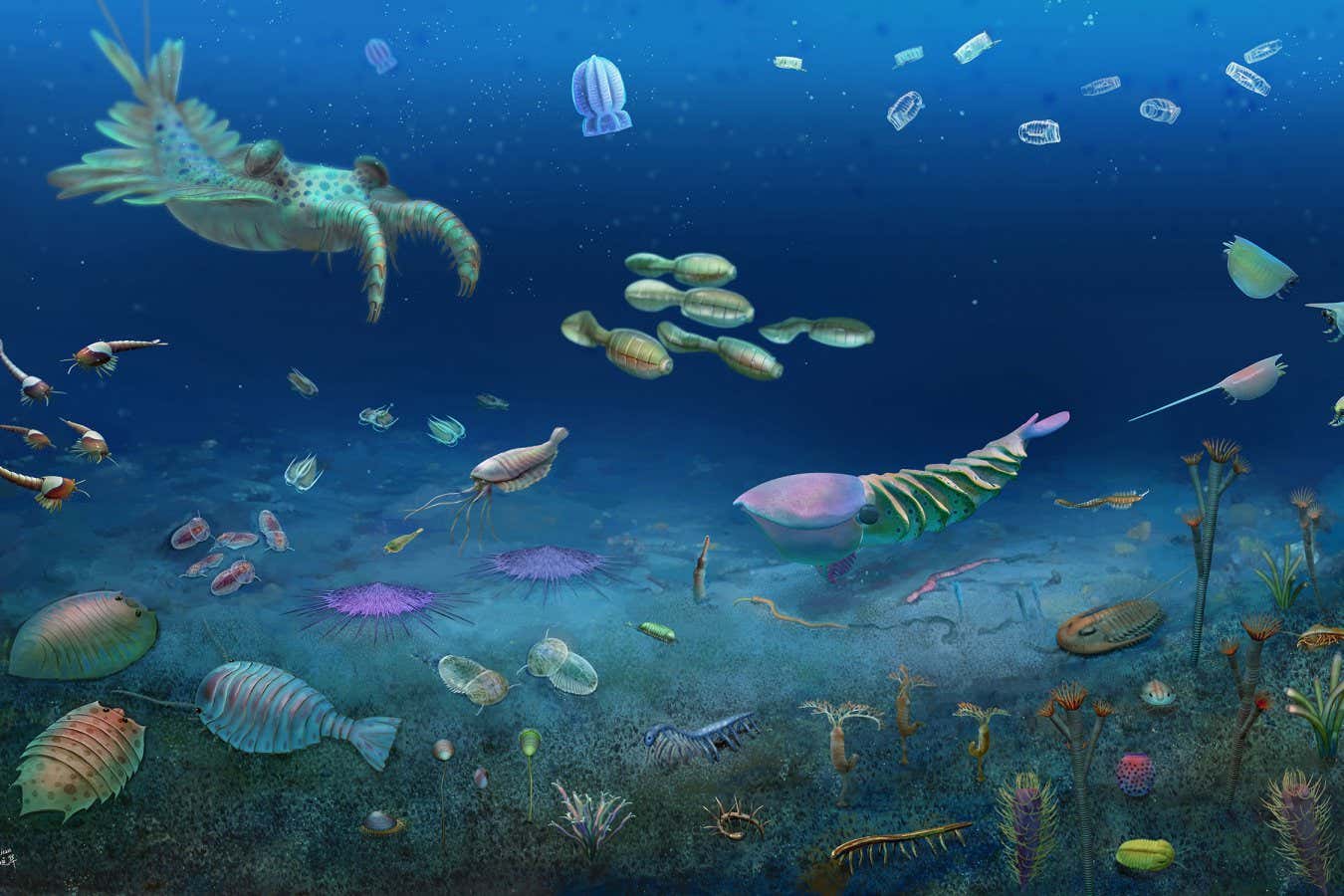

An artist’s illustration of life in Earth’s oceans at the time of the Huayuan biota Dinghua Yang An extraordinary

An artist’s illustration of life in Earth’s oceans at the time of the Huayuan biota

Dinghua Yang

An extraordinary 512-million-year-old fossil site has been discovered in southern China, preserving in vivid detail almost an entire ecosystem from a time shortly after Earth’s first mass extinction event.

The fossils date from the Cambrian period, which began 541 million years ago. The early Cambrian saw an explosion of diversity in animal life which gave rise to most of the major groups alive today.

But this flourishing came to a halt with the Sinsk event around 513.5 million years ago, when oxygen levels in the ocean fell, killing off several groups of animals.

Han Zeng at the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology in China and his colleagues began finding fossils at a quarry in the mountainous region of Huayuan County in Hunan Province in 2021.

So far, they have analysed 8681 fossils from 153 species, nearly 60 per cent of which are new to science. The team has christened this ancient ecosystem the Huayuan biota and say the site is comparable and possibly superior to the most famous Cambrian fossil site, the Burgess Shale in Canada.

The assemblage consists of 16 major groups of animals that are thought to have lived in the deep ocean and appear to have been less impacted by the Sinsk event.

“Our previous knowledge of the Sinsk extinction event only came from the fossil record of skeletal animals such as archaeocyathid sponge reefs, trilobites and small shelly fossils,” says Zeng.

The Huayuan biota also consists of many different species of soft-bodied animals. “We found that the extinction mainly destroyed the shallow-water environment, and the deep-water environment at the edge of the continental shelf, where the Huayuan biota is situated, was less affected,” says Zeng.

A fuxianhuiid arthropod from the Huayuan biota

Han Zeng

Most of the fossils found are arthropods, related to today’s insects, spiders and crustaceans. The fossils also include molluscs, shelled creatures called brachiopods and cnidarians – relatives of jellyfish.

An 80-centimetre-long arthropod named Guanshancaris kunmingensis is the largest animal recovered from the quarry and would have been the predator at the top of the pile in the Huayuan ecosystem.

Another arthropod, Helmetia, is one of two genera that were previously found only in Canada’s Burgess Shale but have now been found at Huayuan, which was then, as now, “halfway across the world,” says Zeng. “This indicates that early animals were able to spread over a very long distance, which was most likely made by the transportation of animal larvae in ocean currents,” he says.

Zeng says the reason for the exquisite preservation found at the site is that the animals were buried very quickly under a slurry of fine mud. The soft parts of animals are preserved in extraordinary detail, including walking legs, antennae and tentacles, respiratory organs such as gills, the pharynx and guts in many animals and even eyes and neural tissues.

Allonnia, a Cambrian sea creature thought to be similar to sponges

Han Zeng

Joe Moysiuk at Manitoba Museum in Canada says the diversity of species and quality of preservation “vaults Huayuan into the top tier of Cambrian fossil sites.”

We know that the Sinsk event in the mid-Cambrian saw major declines in some groups of sponges, trilobites, and others, he says, but we have very little information about its impact on most animal groups.

“Discoveries like the Huayuan biota give us critical snapshots of this soft-bodied biodiversity during the Cambrian, filling in missing frames in the proverbial tape of Earth’s history,” says Moysiuk.

Tetsuto Miyashita at the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa says the two most famous Cambrian fossil sites to date are the 520-million-year-old Chengjiang biota in China and the 508-million-year-old Burgess Shale in Canada.

“But it’s like comparing Bach’s court ensemble and the Beatles — we need to understand where the differences come from before knowing what story they tell us on the whole,” says Miyashita. “A new biota like this is important because it helps palaeontologists tease apart the effects of geography, mass extinction and ocean depths and chemistry.”

One important group is conspicuously absent from Huayuan. “Where are the fish?” says Miyashita. “Were they undergoing a pinch globally and very rare, or was there any other ecological reason that we don’t find fish chasing after so many species of soft-bodied animals?”

Zeng says his team hasn’t yet sifted through all of the fossils they have collected. “There will be new species coming out. Fish may be there, and we shall wait and see,” he says.

Topics: