How growing up in war really affects an 11-year-old child

Fergal KeaneSpecial correspondent BBC Content warning: this article includes details about the impact of conflict on children in war

Fergal KeaneSpecial correspondent

BBC

BBCContent warning: this article includes details about the impact of conflict on children in war zones and descriptions of injuries that some readers may find distressing.

The first thing was that Abdelrahman’s dad was killed. The family home was struck by an Israeli air strike. The boy’s mum, Asma al-Nashash, 29, remembers that “they brought him out in pieces”.

Then on 16 July 2024 an air strike hit the school in Nuseirat, central Gaza. Eleven-year-old Abdelrahman was seriously wounded. Doctors had to amputate his leg.

His mental state began to deteriorate. “He started pulling his hair and hitting himself hard,” Asma recalls. “He became like someone who has depression, seeing his friends playing and running around… and he’s sitting alone.”

When I meet Abdelrahman at a hospital in Jordan in May 2025, he is withdrawn and wary. Dozens of children have been evacuated to the Kingdom from Gaza for medical treatment.

“We will return to Gaza,” he tells me. “We will die there.”

Abdelrahman is one of thousands of traumatised children I’ve met in my nearly four decades of reporting on conflicts. Certain faces are embedded in my memory.

Some as though I had only met them yesterday. They reflect the depth of terror inflicted on children in our time.

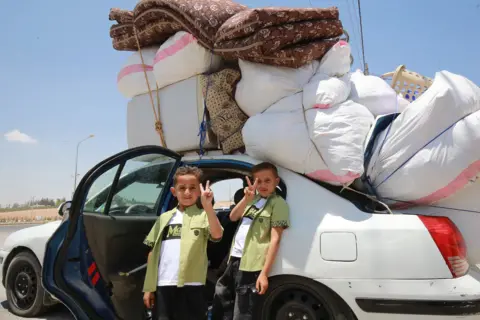

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty Images AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty Images AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesThe first was on a hilltop in Eritrea in the mid-1980s. Adonai Mikael was a child victim of an Ethiopian napalm strike, crying in agony as the wind blew dust on to his wounds. The cries, the expression of pure agony in his eyes sent me fleeing from the tent where he was being treated.

In Belfast a few years later, I remember a boy following the coffin of his father, blown up by the IRA. Never before had I seen such a distance in anyone’s eyes.

In Sierra Leone during the civil war, there was the girl whose hands were hacked off by a drunken militiaman; from Soweto there is the image of a child helping her mother mop the blood of a murder victim on their doorstep; and in Rwanda the boy who broke down when I asked him why the other children called him “Grenade” – a moment of insensitivity I will always regret.

He had been wounded by an explosion that killed his parents.

Figures underscore the sheer scale of the crisis. In 2024, 520 million children were living in conflict zones – one in every five children worldwide – according to an analysis by the Peace Research Institute Oslo, which pieced together conflict records with population data to arrive at the estimate.

Prof Theresa Betancourt, author of Shadows into Light, a book about former child soldiers, calls this “the largest humanitarian disaster since World War Two”.

She warns trauma has an impact that lasts long into the future. “[It can affect] the developing architecture of the brain in young children, with lifelong consequences for learning, behaviour, and both physical and mental health.”

But given how much time has been spent researching the impact of war on children’s minds, what can help?

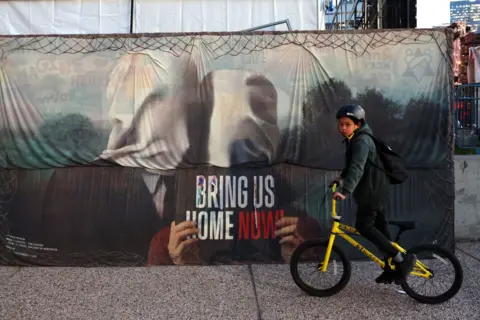

This is a question that has never been more relevant following this period of multiple global conflicts that have affected millions of children: from those Sudanese children who, in October, saw their mothers and sisters raped by militiamen in el-Fasher, Darfur; the youngsters abducted from Israel by Hamas on 7 October, 2023, many having witnessed the slaughter of family and neighbours; the children of Bucha in Ukraine whose parents were among the people massacred by Russian troops in February 2022; and the hundreds of thousands of children like Abdelrahman who have endured more than two years of war in Gaza.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty Images Getty Images

Getty ImagesI should declare a personal interest. I suffered from post traumatic stress disorder – PTSD both as a child in a broken home, and later as an adult, witnessing war and genocide. Though different from experiencing war as a child, I know the symptoms all too well: the extreme anxiety, hypervigilance – being constantly on guard against threats – flashbacks, nightmares, and depression. The symptoms were severe enough to require several hospitalisations.

Personal experience has made me intensely curious about how children respond and are treated.

“The evidence is quite solid across different studies that the exposure to war and displacement is associated with a higher risk of mental health problems,” says Michael Pluess, a professor of psychology at the University of Surrey.

He has carried out long-term research into the children of Syrian war refugees, and cautions against making assumptions. “It’s important to recognise that children differ in how they respond.”

A variety of factors can influence the outcome. How long was the child exposed to the traumatic events? Were they physically wounded? Did they lose an important person in their life, or see them killed or injured? Did they have physical security and emotional support in the aftermath?

In a sample of 2,976 children from Bosnia-Herzegovina – all of whom had been exposed to war and were aged between nine and 14 – high levels of post-traumatic symptoms and grief symptoms were reported.

Getty Images

Getty Images Getty Images

Getty Images Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut there is the potential for long-term health damage – heart disease, autoimmune problems – linked to “toxic stress”, where the body is flooded with hormones like cortisol and catecholamines, which produce adrenaline.

There is also a developing field of research into epigenetics, which asks whether the experience of trauma by one generation can show up in later generations through changes in the way our genes behave.

Are we more susceptible to, say, poor mental health, addictions or other health problems if our families have a history of trauma – and how much has this to do with genetics versus our family setups and everyday lives?

The family drip-feed effect

Epigenetics is a tentative and debated area of scientific research with much still to be learned.

“I think there is some evidence that there is a sort of intergenerational transmission of trauma,” says Prof Pluess. “Some of that or much of that will happen through social practice rather than biological practice, but there’s some evidence to suggest that there are some epigenetic factors as well.”

Prof Metin Başoğlu, director of the Istanbul Centre for Behavioural Sciences, is sceptical. However, he says it is possible that certain temperament traits (for example, predispositions that are transmitted genetically across generations) might make some people more vulnerable to traumatic events.

During research for a book on my own PTSD, I remember a conversation with one of Britain’s most eminent experts in the field, Prof Simon Wessely, former president of the Royal College of Psychiatrists.

I wondered whether my own family history – great-grandparents born during the Irish famine, a grandmother who was traumatised by her war experiences in the 1920s – could have made me more genetically predisposed to PTSD?

“There is simply no way of knowing, without studying a representative sample group from the same area, with ancestors born in the same place and subjected to the same conditions,” he told me. “I can’t do it on one person…

“What I think is much easier to understand – and, I think, is also the most powerful – is the influence of our background. And it’s absolutely impossible for you to have grown up in the household that you did, with the interests that you have, for that not to have the same effect on you.”

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty Images AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesThere is broader consensus that trauma is a family crisis. It isn’t only a question of what a child witnesses or survives – there is also the impact on adults.

“Not only do children in war zones face the death of caregivers and traumatic separations,” says Prof Betancourt, “but caregivers experiencing their own trauma and distress may not be fully available to help protect and guide their children through the horrors of war.”

Prof Pluess’s research among Syrian refugees supports this. Among the 80% of children found to be vulnerable to more than one psychological disorder, family circumstances were critical.

Around 1,600 families took part in a study, published in 2022, of Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Prof Pluess says that children’s living conditions (such as access to safe housing, food, and schooling) were found to be “about 10 times more predictive of their mental health”.

Children who adapted more healthily may have “had a social environment that was very protective, maybe the parents were able to shield them, maybe they had close friendships, relationships, maybe they have access to school, all those external things that sort of buffer the negative impact of war exposure.”

The roots of this knowledge in Britain go back to WW2 and the experience of children who lived through the Blitz – the eight months of German air attacks between September 1940 and May 1941.

Getty Images

Getty Images Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis via Getty Images

Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis via Getty Images Fox Photos/Getty Images

Fox Photos/Getty ImagesProf Edgar Jones, of King’s College London, points to a study of 212 children treated at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children during the war. When researchers went back to the children in 1949 – four years after the conflict ended – they found only 21% had recovered. The role of parents – both positive and negative – emerged as an important finding.

“The severity of a child’s reaction to bombing was judged to be influenced by their parents’ response to the trauma either to accentuate or calm their anxiety,” says Prof Jones.

Overcoming fear and establishing control

In my own experience, therapy and medication helped, but also the ongoing support of family and friends. Without the power of caring relationships I don’t believe I could have emerged from the darkness.

I was also encouraged to confront my avoidance of anything that might remind me of the trauma. For example, I went through a long period of avoiding travel to the continent of Africa, fearing that simply being there would trigger reminders of the Rwandan genocide. But my therapist gradually encouraged me to face the fear. It took several years but I did return, and continue to visit places there that are dear to my heart.

Prof Başoğlu pioneered the use of what is called CFBT – Control Focused Behavioural Treatment – among survivors of the 1999 Turkish earthquake, which killed about 18,000 people.

The idea is to encourage the individual to take control of their fear of the event recurring. In the case of children who were constantly clinging to their parents, this was attempted by encouraging them to get used to sleeping alone.

“Once they overcome their fear, all the traumatic stress reactions that are associated with fear also improve,” Prof Başoğlu says.

Israeli psychologists working with children released from Hamas captivity after the 7 October attacks also stress the importance of re-establishing a sense of control.

Getty Images

Getty Images AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty Images Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn a paper for the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health journal, a team of Israeli specialists wrote that this was achieved “by providing survivors with information and space to express their concerns while ensuring that their needs and voices are heard”.

But successful interventions depend greatly on creating a stable environment where the fear of being killed or maimed is not an ever-present reality.

“What they also need is that their parents are well, that they live in a safe place, that they have access to education, that they have a routine, that they have some predictability,” says Prof Pluess.

This is rarely certain in areas ravaged by war. Ceasefires break down. Front lines become frozen. The displaced are stuck in camps.

‘We were dehumanised’

Still, those words about a safe place bring to mind my friend Beata and the difference stability made to her life.

She was 15 years old when the Rwandan genocide – the worst mass slaughter since the Nazi Holocaust – erupted in 1994. Up to 800,000 people, mostly members of the Tutsi minority, were massacred over a period of 100 days.

As a reporter I travelled on the convoy that evacuated dozens of orphaned children – Beata Umubyeyi Mairesse among them – through roadblocks manned by the murderous Interahamwe militia. It was a terrifying experience, but especially for the children whose families had been killed.

From roadblock to roadblock, we did not know if the machete-wielding gangs would attack.

Years later when she was researching her experiences (later published in a book, The Convoy), Beata got in touch. I remember being struck by her composure and openness. She is married with two children, lives in France and is now a successful writer.

“The first thing that helped me was exile to France, leaving the scene of the genocide. I found myself safe, in a peaceful place, with shelter, a foster family who took care of all my material needs, and the opportunity to see a psychologist. I went back to school in September, and that helped me too.”

VCG via Getty Images

VCG via Getty Images Mirrorpix/Getty Images

Mirrorpix/Getty Images Liaison/ Getty Images

Liaison/ Getty ImagesBeata was joined by her mother who also survived. Her father had died before the slaughter.

Composed as she was, there were lingering terrors. She panicked one night when classical music was played on the radio – similar to music played on Rwandan radio the night the genocide began. Fireworks or the sound of hunters shooting sent her hiding under a desk in class “because I thought war had broken out in France”.

I wondered if she makes a conscious effort to protect her children from the traumatic inheritance of genocide.

“There are things that are difficult to tell your children, how we were dehumanised, how I was almost raped. The term ‘unspeakable’ makes sense when passing on stories to children. We are afraid of contaminating them with our trauma.”

But for Beata, nuance is vital. “Their only image of Rwanda should not be the genocide. I told them stories from my childhood and every time I went there I brought them back fruit so that they could also discover a country full of flavour.”

Although she lives a full and happy life, Beata still suffers from anxiety and takes anti-depressants to deal with insomnia. I also use medication, and like Beata I do not see it as a burden or a stigma.

Rather I count myself fortunate to be able to access care and medicine.

Creating a safe community is also seen as critical by many experts.

“They’re not just victims of mental health,” says Prof Pluess. “They’re little people with interests and that’s why they need to go to school, they need to have opportunities to play together – and that might be as important as dealing with the mental health problems that they’re facing.”

Psychologists working in Gaza are well aware of these needs. Davide Musardo, who volunteered with Medecins Sans Frontieres, has written of trying to provide therapy against the background of drones and explosions.

“In Gaza, one survives but the exposure to trauma is constant. Everything is missing, even the idea of a future. For people, the greatest anguish is not of today — the bombs, the fighting, and the mourning — but of the aftermath. There is little confidence about peace and reconstruction, and the children I saw in the hospital showed clear signs of regression.”

It is possible, in devastated Gaza, that the current ceasefire will become a permanent peace, allowing rebuilding, and the restoration of family life and schooling. Possible but by no means certain. In Sudan there are attempts to re-start talks about peace but little optimism for their outcome. The war in Ukraine, and many other wars grind on every day.

Trauma is as old as war itself. Politicians, journalists, and experts looking to the aftermath of a conflict often ask, “What will happen when the killing stops?” But somewhere else the killing will continue. That is the relentless tragedy of children caught in wars they did not start, over which they have no control. For all the knowledge gained about treating trauma, humanity is far from dealing with its root cause – war itself.

Additional reporting by Harriet Whitehead

Top picture credit: EPA/Shutterstock

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. You can now sign up for notifications that will alert you whenever an InDepth story is published – click here to find out how.