How everyday foam reveals the secret logic of artificial intelligence

Foams appear in everyday life as soap suds, shaving cream, whipped toppings and food emulsions like mayonnaise. For many

Foams appear in everyday life as soap suds, shaving cream, whipped toppings and food emulsions like mayonnaise. For many years, scientists believed foams behaved much like glass, with their tiny components locked into disordered but essentially fixed positions.

New research now challenges that long-standing view. Engineers at the University of Pennsylvania have found that while foams keep their overall shape, their interiors are in constant motion. Even more unexpectedly, the mathematics describing this motion closely resemble deep learning, the technique used to train modern artificial intelligence systems.

This finding suggests that learning, in a broad mathematical sense, may be a shared organizing principle across physical, biological and computational systems. The work could also guide future efforts to create materials that adapt and respond to their surroundings. It may even help scientists better understand living structures that must continually reorganize themselves, such as the internal scaffolding of cells.

Bubbles That Never Settle

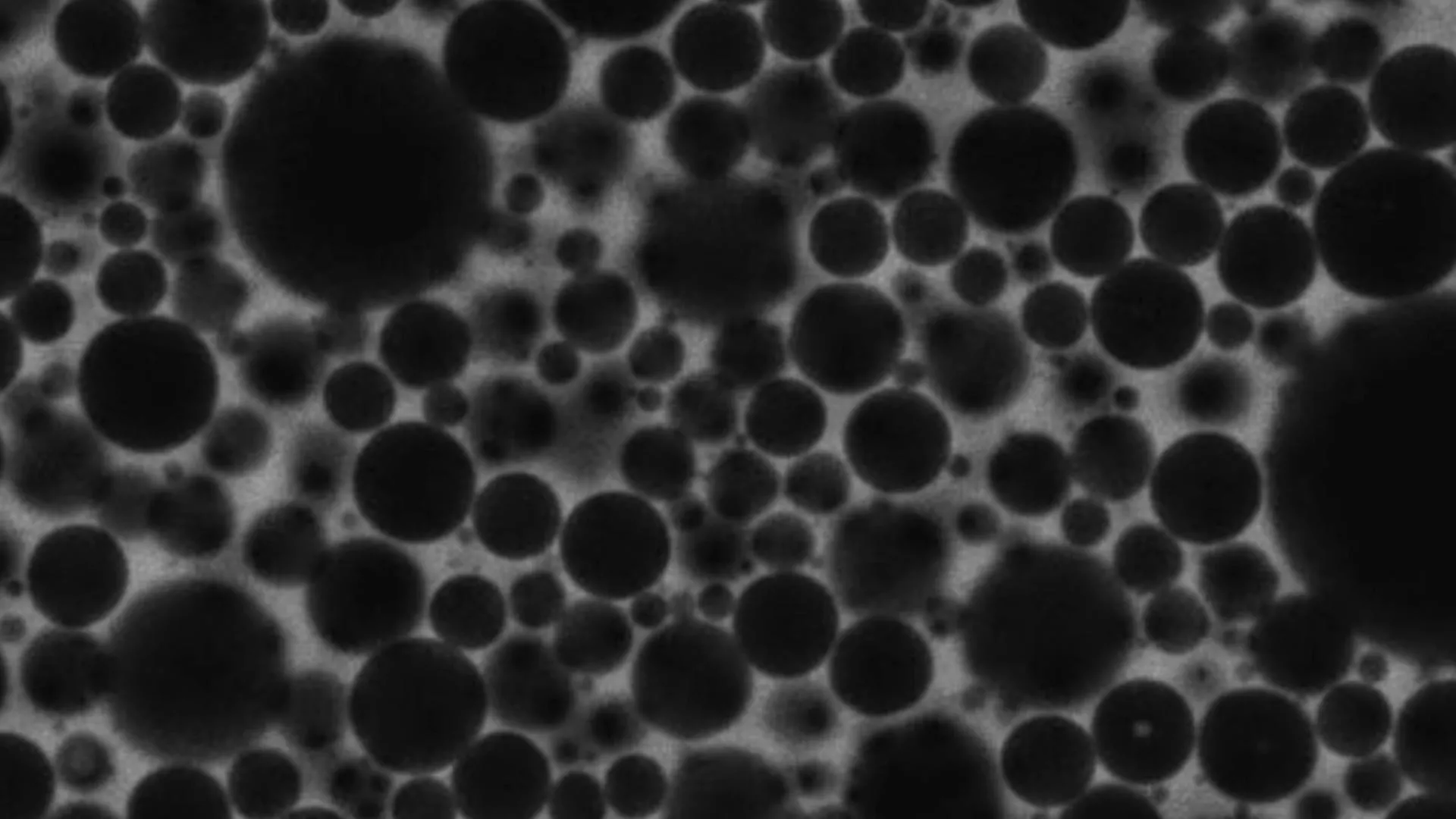

In a study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the researchers used computer simulations to follow the movement of bubbles within a wet foam. Instead of eventually becoming stationary, the bubbles kept wandering through many possible arrangements.

From a mathematical viewpoint, this behavior closely resembles how deep learning works. During training, an AI system repeatedly adjusts its parameters — the information that defines what an AI “knows” — rather than locking into a single final state.

“Foams constantly reorganize themselves,” says John C. Crocker, Professor in Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering (CBE) and the paper’s co-senior author. “It’s striking that foams and modern AI systems appear to follow the same mathematical principles. Understanding why that happens is still an open question, but it could reshape how we think about adaptive materials and even living systems.”

Why Foams Defied Traditional Physics

Foams often behave like solids at the human scale. They generally keep their shape and can spring back after being squeezed. At much smaller scales, however, foams are considered “two-phase” materials, made of bubbles suspended in a liquid or solid background.

Because foams are easy to make and observe while still displaying complex mechanical behavior, scientists have long used them as model systems to study other dense and dynamic materials, including living cells.

Traditional theories treated foam bubbles like rocks rolling across an energy landscape. In this view, bubbles move downhill into positions that require less energy to maintain, then stay there. This idea helped explain why foams appear stable once formed, much like a boulder resting at the bottom of a valley.

A Mismatch Between Theory and Reality

When researchers examined real foam data, they found the behavior did not align with these predictions. According to Crocker, signs of this mismatch appeared nearly two decades ago, but there were no suitable mathematical tools to fully explain what was happening.

“When we actually looked at the data, the behavior of foams didn’t match what the theory predicted,” Crocker says. “We started seeing these discrepancies nearly 20 years ago, but we didn’t yet have the mathematical tools to describe what was really happening.”

Solving this puzzle required a new approach, one that could describe systems that continue changing without ever settling into a single, fixed arrangement.

Lessons From Artificial Intelligence

Modern AI systems learn by continuously adjusting numerical parameters during training. Early approaches tried to push these systems toward a single optimal solution that perfectly matched their training data.

Deep learning relies on optimization methods related to a mathematical technique called gradient descent. These methods repeatedly guide a system toward configurations that reduce error, step by step, much like moving downhill across a landscape.

Over time, researchers realized that pushing models too far into the deepest possible solutions caused problems. Systems that fit their training data too precisely became fragile and performed poorly on new information.

“The key insight was realizing that you don’t actually want to push the system into the deepest possible valley,” says Robert Riggleman, Professor in CBE and co-senior author of the paper. “Keeping it in flatter parts of the landscape, where lots of solutions perform similarly well, turns out to be what allows these models to generalize.”

Foam and AI Follow the Same Rules

When the Penn team reexamined their foam data using this perspective, the similarity became clear. Foam bubbles do not settle into deep, stable positions. Instead, they continue moving within broad regions where many configurations are equally viable.

This ongoing motion closely parallels how modern AI systems operate during learning. The same mathematics that helps explain why deep learning works also captures what foams have been doing all along.

Implications for Materials and Living Systems

The findings raise new questions in a field many believed was already well understood. That alone may be one of the study’s most important contributions.

By showing that foam bubbles are not frozen in glass-like states but instead move in ways similar to learning algorithms, the research encourages scientists to rethink how other complex systems behave.

Crocker’s team is now revisiting the system that first sparked his interest in foams: the cytoskeleton, the microscopic framework inside cells that supports life. Like foam, the cytoskeleton must continually reorganize while preserving its overall structure.

“Why the mathematics of deep learning accurately characterizes foams is a fascinating question,” says Crocker. “It hints that these tools may be useful far outside of their original context, opening the door to entirely new lines of inquiry.”

This research was conducted at the University of Pennsylvania School of Engineering and Applied Science and supported by the National Science Foundation Division of Materials Research (1609525, 1720530).

Additional co-authors include Amruthesh Thirumalaiswamy and Clary Rodríguez-Cruz.