How Australian teens are planning to get around their social media ban

Under 16s in Australia will be banned from social media on 10 December Mick Tsikas/Australian Associated Press/Alamy The world’s

Under 16s in Australia will be banned from social media on 10 December

Mick Tsikas/Australian Associated Press/Alamy

The world’s first attempt to ban all children under 16 from social media is about to come into force in Australia – but teenagers are already fighting back.

Announced in November last year by the Australian prime minister Anthony Albanese, the prohibition is due to come into effect on 10 December. On that day, every underage subscriber of services including Instagram, Facebook, TikTok, YouTube and Snapchat will have their accounts deleted.

If the social media companies fail to remove teenagers from their platforms, they face fines of up to AUS$49.5 million (£25 million). Neither parents nor children can be punished, however.

The law is being closely watched by the rest of the world, with a similar ban being considered by the European Commission. Until now, much of the debate around it has focused on how it will be enforced and what kind of age-verification technologies will be put in place, along with possible detrimental impacts on teenagers who are dependent on social media for connection to their peers.

But as the online D-Day looms, teenagers have already begun preparing to outmanoeuvre the effort to curtail their digital lives. The most high-profile example has been an 11th hour bid by two 15-year-olds, Noah Jones and Macy Neyland, both from New South Wales, to mount a case in the nation’s highest court to seek to have the social media ban overturned.

“If I am truthful, kids have been planning getting around the ban for months and months, but the media is only hearing it now because of the countdown,” says Jones.

“I know kids who are hiding old family devices in their school lockers. They moved accounts to their parents or older siblings ages ago and verified with adult ID, and their parents have no clue,” he says. “We know about algorithms, so kids are following older-people groups like gardening or over-50s walking groups, and we comment in professional language so we don’t get picked up.”

Jones and Neyland were originally seeking an injunction to have the ban delayed, but instead decided to push for their opposition to the ban to be adjudicated as a special constitutional law case.

The pair had a major victory on 4 December, when Australia’s High Court decided it would hear their case as early as February. The main argument being mounted by the teenage plaintiffs is that the ban is an unfair burden on their implied freedom of political communication. They also contend in their application that the policy will sacrifice “a considerable sphere of freedom of expression and engagement for 13-to-15-year-olds in social media interactions”.

Libertarian advocates Digital Freedom Project, led by New South Wales politician John Ruddick, are back the pair. “I’ve got an 11-year-old and a 13-year-old kid and they’ve been telling me for months that everyone in the playground’s talking about it,” he says. “They’re all on social media. They all benefit from social media.”

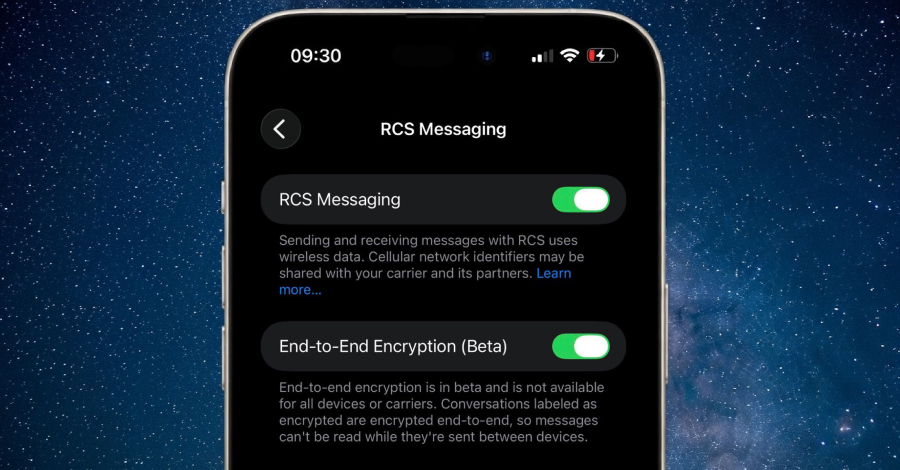

Ruddick says that his children are saying that kids are discussing how to get around the ban, including the use of virtual private networks (VPNs), new social media apps and ways of foiling the age-verification technology.

Catherine Page Jeffery at the University of Sydney, Australia, says it is only as the deadline for the ban looms that it is “getting real” for teenagers. “My impression has been that up to this point, young people haven’t really believed that it’s actually happening,” she says.

She says her own children are already discussing workarounds with their friends. Her younger daughter has already downloaded another, alternative social media platform called Yope. This site isn’t on the government’s list yet, but, along with several others, including Coverstar and Lemon8, has been warned by the government to self-assess so it doesn’t fall foul of the ban.

Lisa Given at RMIT University in Melbourne, Australia, says with kids scattering to all corners of the internet onto new and obscure social media platforms, parents will lose visibility of their children’s online lives. She also expects a significant proportion of parents to help their kids pass age-verification checks by offering up their own faces.

Susan McLean, a leading Australian cybersecurity expert, says it is going to be an “utter game of whack-a-mole” as new sites pop up, kids migrate onto them and then the government adds them to the banned list. She says that rather than take social media from teenagers, governments should force the big companies to fix the algorithms that feed inappropriate content to children.

“The government is just so stupid in their thinking,” she says. “You can’t ban your way to safety, unless you ban every single app or platform that allows kids to communicate.”

McLean says that a couple of weeks ago, a teenage student said to her: “If the reason for this ban is to keep bad adults away from children, then why are the bad adults allowed to stay on the platform and I have to leave?”

Noah Jones, the teenage plaintiff in the high court case, puts it even more bluntly. “There’s no newspaper big enough for me to learn what I can see in 10 minutes on Instagram,” he says. “My friends say that paedos got off with no consequences and we got banned.”

Topics: