Greenlanders unnerved as Arctic island finds itself in geopolitical storm

Katya AdlerNuuk, Greenland ‘We just want to be left alone’: Greenlanders on US President Trump’s takeover threats US Secretary

Katya AdlerNuuk, Greenland

US Secretary of State Marco Rubio will meet Danish officials next week to discuss the fate of Greenland – a semi-autonomous territory of Denmark that President Donald Trump says he needs for national security.

The vast island finds itself in the eye of a geopolitical storm with Trump’s name on it and people here are clearly unnerved.

Yet when you fly in, it looks so peaceful. Ice and snow-capped mountains stretch as far as the eye can see, interrupted here and there by glittering fjords – all between the Arctic and the Atlantic Oceans.

It is said to sit on top of the world; much of it above the Arctic Circle.

Greenland is nine times the size of the UK but it only has 57,000 inhabitants, most of them indigenous Inuit.

You find the biggest cluster of Greenlanders on the south-western coast in the capital, Nuuk. We arrived there as a frozen twilight was creeping across snow-covered pedestrian streets.

Parents dragged their children home from school on sledges, and students mooched their way in and out of brightly-lit malls. Few wanted to talk to us about the Trump-related angst here. Those who did sounded very gloomy.

One pensioner banged his walking stick on the ground in emphasis as he told me the US must never plant its flag in Greenland’s capital.

A lady who said she was mistrustful of everyone these days, and didn’t give her name, admitted she was “scared to death” about the prospect of Trump taking the island by force after she watched his military intervention in Venezuela.

Meanwhile, 20-something pottery-maker Pilu Chemnitz said: “I think we are all very tired of the US president. We have always lived a quiet and peaceful life here.

“Of course, the colonisation by Denmark caused a lot of trauma for many people but we just want to be left alone.”

Never mind opposing a takeover by the US, which 85% of Greenlanders say they do, most also say they favour independence from Denmark – although many tell me they also appreciate the subsidies coming from there that help prop up their welfare state. While rich in untapped natural resources, poverty is a real issue here in Inuit communities.

Overall, Greenlanders want a bigger, louder say, not only in their domestic policies, but in foreign affairs too.

I went to the island’s modest-looking parliament, the body of it built in a Scandinavian style with wooden slats and painted the same burnished red as the Greenlandic flags fluttering by the entrance.

No security checks. All pretty relaxed. Except for the roaring polar bear emblem – a symbol of Greenland, etched onto every sliding glass doors we pass.

I was there to meet Pipaluk Lynge-Rasmussen, co-chair of the foreign affairs committee in parliament. She is an MP with the pro-independence Inuit Ataqatigiit party that is part of the coalition government here.

“I think it’s very important for us to speak out about what we want as a people,” she told me. “We have always worked towards independence when we got home rule in 1979 and more independence in 2009.”

I asked Lynge-Rasmussen if she felt that big global powers – the US, Denmark, Nato, and the EU – were talking a lot about Greenland right now, rather than to the islanders about their fate.

She nodded vigorously. Surprisingly, perhaps, she blames Denmark more than she blames Trump for overlooking Greenlanders’ wants and needs.

Even though Greenland and the Faroe Islands are part of the Kingdom of Denmark, she says, she feels they have always been treated like second-class citizens.

But Lynge-Rasmussen insisted that Greenlanders should not see themselves as victims in the current situation. Instead, she suggests they use the international spotlight now on them to show off their importance and push for their priorities.

What of the meeting next week with Rubio, I asked?

“I hope the meeting will end with understanding and compromise,” she answered.

“Maybe doing business with [the US] from here… maybe co-operating on trade, or mining, having more American [military] bases on Greenland, perhaps?”

Under a bilateral agreement with Denmark dating back to 1951 the US may bring as many US troops as it wants to Greenland.

This has left European allies wondering out loud why Trump feels the need to “take” the island unilaterally: whether buying it – seemingly Washington’s preferred option, or encouraging Greenlanders to vote in a plebiscite to become part of the US, or taking Greenland by force, something the Trump administration has refused to rule out.

It wouldn’t take much flexing of military muscles. Greenland has few trained soldiers and no military bases of its own.

Trump and US Vice-President JD Vance justify their need to “take” Greenland because they say Denmark doesn’t do enough to secure the island. Copenhagen disputes this.

It’s also worth noting that the US already has a military base on Greenland – and it chose to radically reduce its presence there from about 10,000 personnel during peak Cold War times to some 200 now.

The US has long taken its eye off Arctic security, until recently.

Trump’s keen interest in the island is likely a mix of:

- perceived national security concerns

- a hunger for the rich natural resources Greenland boasts, including rare earths and minerals

- and his loudly-trumpeted desire to dominate the Americas.

Geographically Greenland is part of North America.

It’s closer to New York City by about 1,000 miles (1,609 km) than to Copenhagen.

This should give Greenlanders pause for thought, opposition MP Pele Broberg of the Naleraq Party told me.

He said people were scared of what Trump would do to Greenland because they were misinformed, largely because of media hysteria.

“It’s true, we are not for sale – but we are open for business. Or we should be.

“Right now we are a colony. We are made to import our goods from Denmark: 4,000km away, rather than from the US which is much closer.”

Broberg described his organisation as the island’s true independence party, pushing he says for freedom, so Greenlanders can trade, on their terms, with any party or country they choose: the US, Denmark or others.

But right now, the US is making demands, rather than business deals between equals.

So what exactly are the national security priorities Trump sees in Greenland?

Briefly put: the shortest route for a Russian ballistic missile to reach continental US is Greenland and the North Pole.

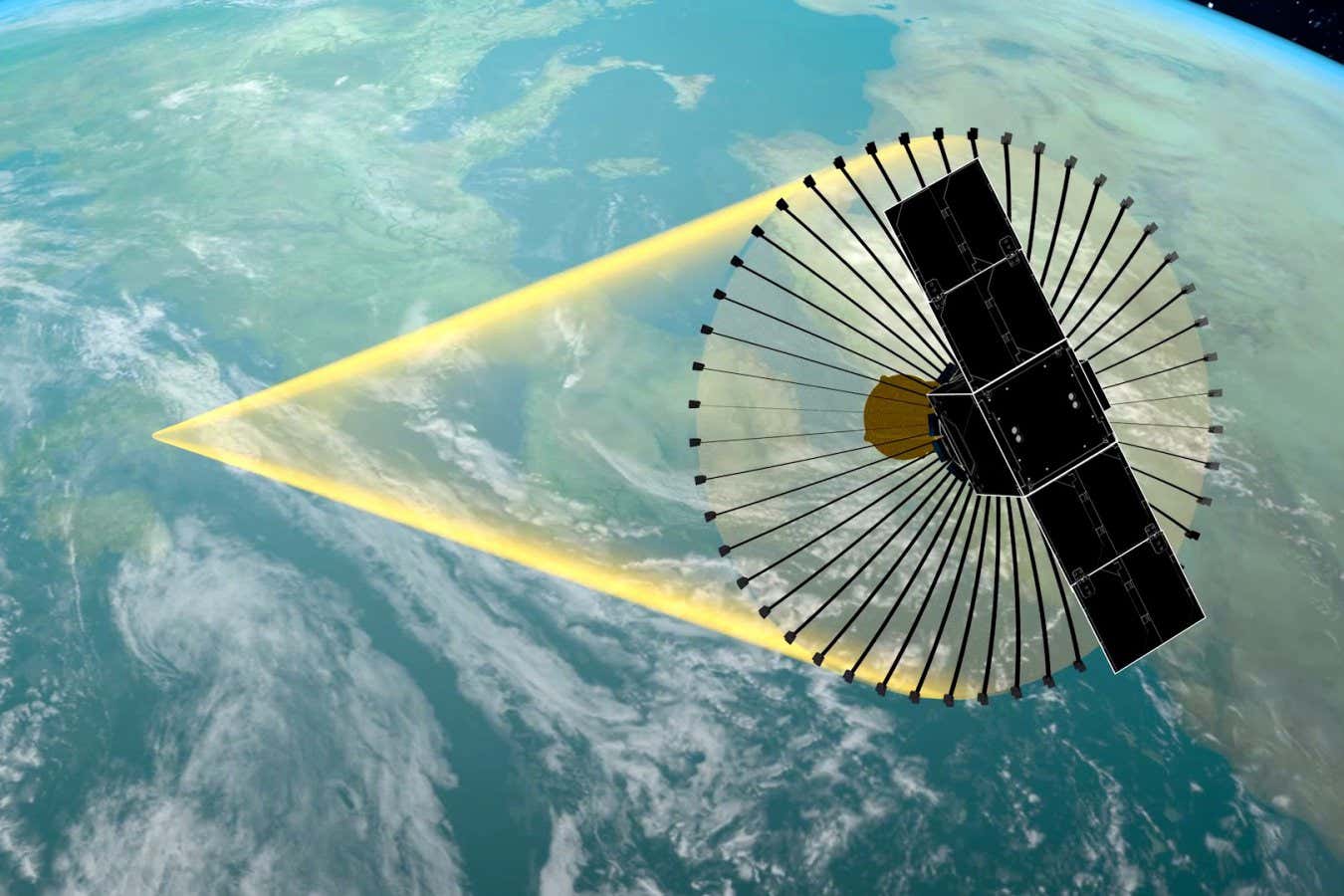

Washington DC already has an early warning air base on the island – but Greenland could serve as a base for missile interceptors as part of the Trump administration’s proposed “Golden Dome” system: a plan to shield the US from all missile attacks.

The US has also reportedly discussed placing radars in waters connecting Greenland, Iceland and the UK – the so-called GIUK Gap. That’s a gateway for Chinese and Russian vessels that Washington wants to track.

There is no evidence to the naked eye when you are in Greenland to back Trump’s recent assertions that there are lots of Chinese and Russian ships currently around the island.

And last week Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson Lin Jian criticised Washington for “using the so-called ‘China threat’ as a pretext for itself to seek selfish gains” in the Arctic.

But Russia and China have been expanding their military capabilities, and have beefed up their co-operation elsewhere in the region – with joint naval patrols and co-developing new shipping routes.

Under pressure from western sanctions over Ukraine, Moscow is keen to ship more to Asia.

Beijing is looking for shorter, more lucrative maritime routes to Europe.

The northern sea route is becoming easier to navigate due to melting ice, and Greenland opened its representation office in Beijing in 2023 in pursuit of deeper ties with China.

When it comes to Arctic security, Nato allies hope to persuade Washington that they are serious. UK Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer reportedly spoke more than once to the US president last week, telling him that Europe will step up its presence even further in the region. He’s also been urging European leaders to increase their cooperation with the US there.

Greenland, Denmark and their Nato allies believe there is room for negotiation with Rubio next week and that, at the very least, Trump swooping in to Greenland militarily is unlikely – though not impossible.

The Arctic powers geographically are Denmark, the US, Canada, Russia, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden. An Arctic Council, representing them all, has long tried to maintain the mantra: high north, low tension.

But military chest-beating and unilateralism from Washington over Greenland, plus a wider scramble for advantage between global superpowers, adds to a real sense of jeopardy in the region.

The decades-long delicate balance in the Arctic, in place since the end of the Cold War, and evenly managed since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, could be dangerously upset.