Friction review: Engaging look at friction shows how it keeps our world rubbing along

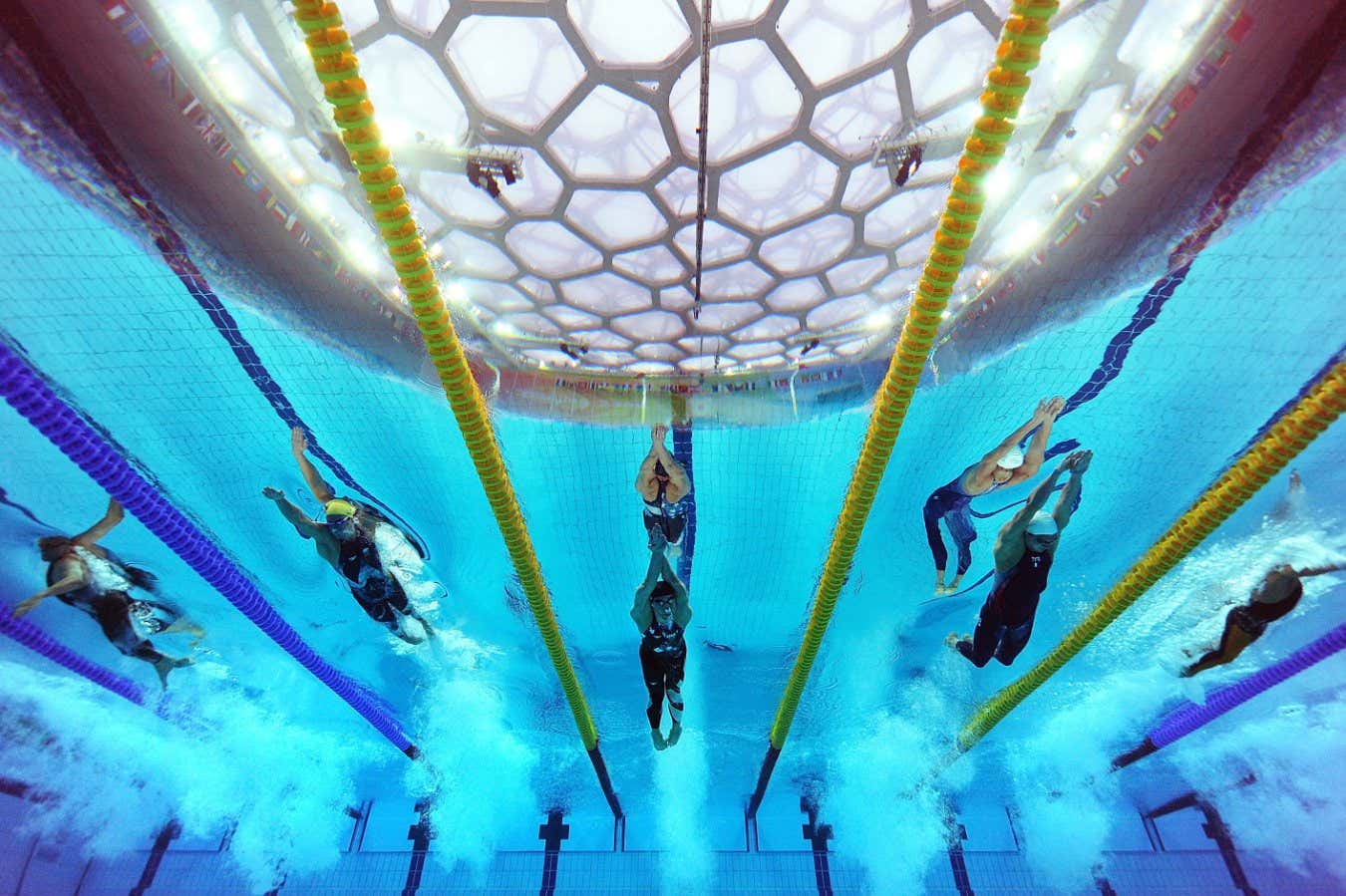

Athletes wearing a friction-reducing swimsuit dominated the 2008 Beijing Olympics Adam Pretty/Getty Images Friction: A biographyJennifer R. Vail, Harvard

Athletes wearing a friction-reducing swimsuit dominated the 2008 Beijing Olympics

Adam Pretty/Getty Images

Friction: A biography

Jennifer R. Vail, Harvard University Press

IN 2009, World Aquatics banned a specific type of swimsuit from all international competitions in water sports, ruling that it gave athletes an unfair advantage. The development of this swimsuit included using NASA’s testing facilities and sophisticated computer software. Some versions had ultrasonically welded seams instead of traditional stitches.

Swimmers who wore the suit broke 23 of the 25 world records set at the Beijing Olympics in 2008. What was it that made this gear so influential such that wearing it ultimately became unsportsmanlike? The secret was that it was an excellent way of reducing the friction between the swimmer’s body and the water.

This is one of many examples of how the seemingly annoying and unglamorous force of friction plays an unexpectedly important part in our world, one captured by Jennifer R. Vail in her book Friction: A biography.

Vail is a tribologist, a scientist who studies the friction, wear and lubrication of materials as they move against each other. For her, “the force that opposes motion is continually driving us forward”. This is key to her book, which, while it can be very technical, is a broad and confident exploration of friction in science, technology and civilisation – a role that will continue into a future laden with technological challenges.

“We study friction because it’s there, and more specifically, because it’s pretty much everywhere,” writes Vail. How did ancient Egyptians move materials for their most impressive projects? How do anoles and geckos walk on walls? What led Teflon to be classified as part of the Manhattan Project? Why do aeroplanes have cambered wings? And what might any of that have in common with research into the mysterious dark matter that fills our universe?

The answer is, again, friction, whether it is in the desert sand, controlled by hairs on animal feet, reduced by human-made materials and naturally secreted proteins, diminished by design, or producing new signatures of dark matter’s presence near black holes. At every scale, from quantum to cosmic, from the bottom of your shoe to the engines of military jets, Vail finds a story about some kind of friction and details it with rigour and enthusiasum.

“

Friction has been at the heart of civilisation, from the days when humans rubbed objects together to start fires

“

While some stretches of Friction read like a collection of nerdy fun facts, Vail also shows how successfully understanding and manipulating the force has incredibly high stakes. Our ability to exploit friction has been at the heart of civilisation, from the early days of humans purposefully rubbing objects together to start fires to creating engines, turbines and everyday devices like contact lenses.

But it is Vail’s emphasis on the future that really encourages the reader to engage. Remarkably, friction accounts for two-fifths of the energy used in manufacturing – either in manfacture or in fighting the friction that arises. A 2011 study, she notes, found that about a third of a petrol tank of the average car at that time was used to overcome friction. In a world where energy is a vital resource and sectors like transport make a major contribution to climate change, reducing the energy used to control friction will be critical for a more sustainable future.

Vail describes attending a 2016 conference where she heard how advances in tribology could save energy annually roughly equivalent to that produced by 3400 million barrels of petrol, about 180 times more than that used every day in the US. Vail’s call for more tribologists to be involved in official energy certifications and audits, and for the discipline to receive a higher profile in science education and communication, could hardly be more urgent and necessary.

Friction is an important book. But it can also be a difficult read, despite Vail’s warm voice, unambiguous excitement about her field and charming sense of humour. Her expertise shines through on every page, but may overwhelm the casual reader.

When I put the book down, I was grateful that I had stuck with it, discovering geared turbofans and sounding out phrases like “elastohydrodynamic lubrication”. Looking at friction’s intricacies adds a crucial layer of understanding for anyone who cares about how the world works, despite, and maybe because of, its many parts constantly rubbing together.

Topics: