Fossilized bones are revealing secrets from a lost world

For the first time, researchers have successfully examined metabolism-related molecules preserved inside fossilized bones from animals that lived between

For the first time, researchers have successfully examined metabolism-related molecules preserved inside fossilized bones from animals that lived between 1.3 and 3 million years ago. These chemical traces offer rare insight into the animals themselves and the environments they once inhabited.

By analyzing metabolic signals tied to health and diet, the scientists were able to reconstruct details about ancient climates and landscapes, including temperature, soil conditions, rainfall, and vegetation. The results, published in Nature, point to environments that were significantly warmer and wetter than those found in the same regions today.

Studying metabolites — the molecules produced and used in digestion and other chemical processes in the body — can reveal information about disease, nutrition, and environmental exposure. While metabolomics has become a powerful tool in modern medical research, it has rarely been applied to fossils. Instead, most studies of ancient remains rely on DNA, which mainly helps establish genetic relationships rather than day-to-day biology.

“I’ve always had an interest in metabolism, including the metabolic rate of bone, and wanted to know if it would be possible to apply metabolomics to fossils to study early life. It turns out that bone, including fossilized bone, is filled with metabolites,” said Timothy Bromage, professor of molecular pathobiology at NYU College of Dentistry and affiliated professor in NYU’s Department of Anthropology, who led the international research team.

Why Fossil Bones Can Preserve Chemistry

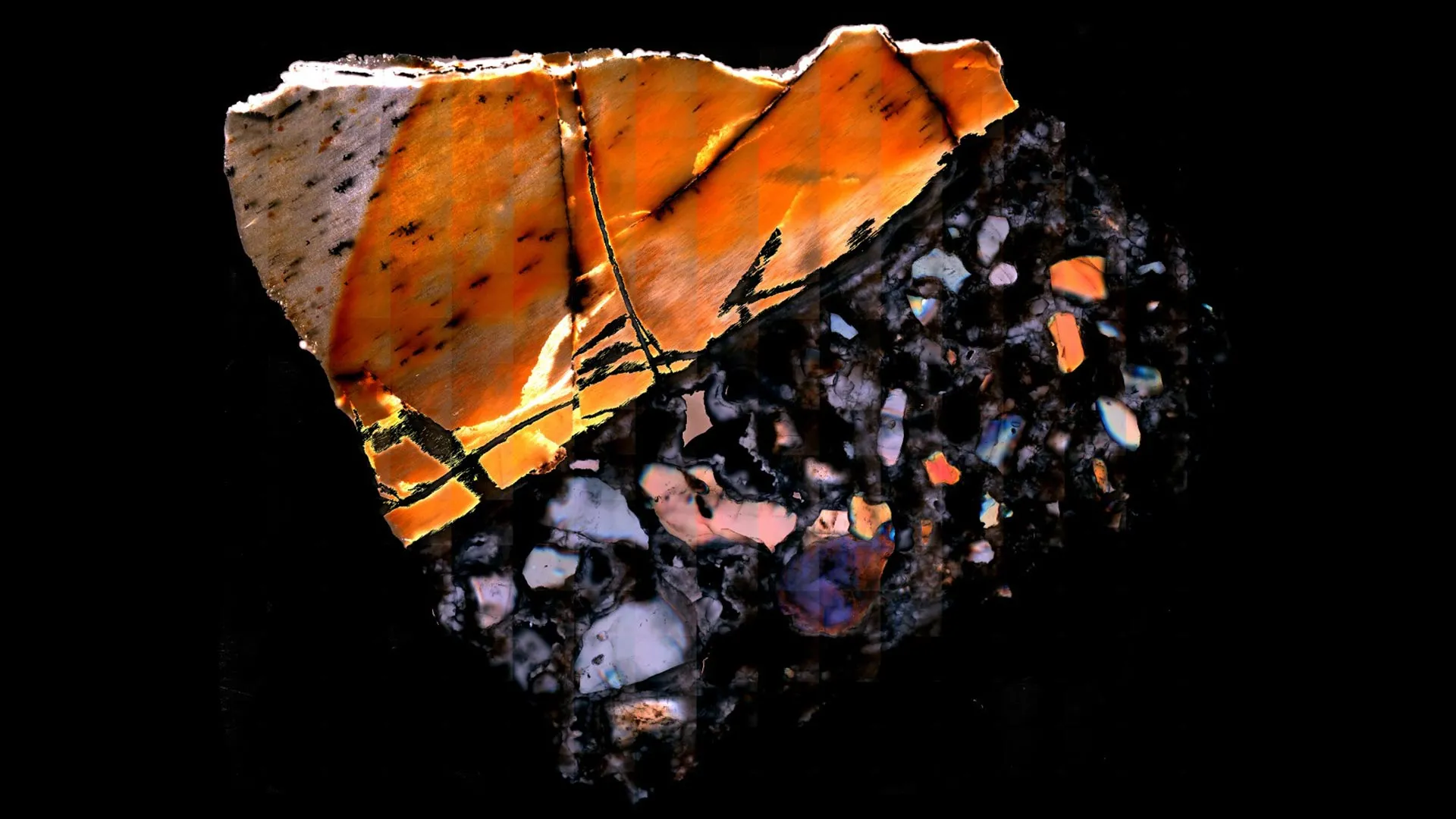

In recent years, scientists discovered that collagen — the protein that provides structure to bones, skin, and connective tissues — can survive in ancient bones, including dinosaur fossils.

“I thought, if collagen is preserved in a fossil bone, then maybe other biomolecules are protected in the bone microenvironment as well,” said Bromage, who directs the Hard Tissue Research Unit at NYU College of Dentistry.

Bone surfaces are porous and filled with tiny blood vessel networks that exchange oxygen and nutrients with the bloodstream. Bromage proposed that during bone growth, metabolites circulating in blood could become trapped inside microscopic spaces within the bone, where they might remain protected for millions of years.

To test this idea, the team used mass spectrometry, a technique that converts molecules into charged particles for identification. Tests on modern mouse bones revealed nearly 2,200 metabolites. The same approach also allowed researchers to detect collagen proteins in some samples.

Testing Fossils From Early Human Landscapes

The researchers then applied this method to fossilized animal bones dating from 1.3 million to 3 million years ago. These samples came from earlier excavations in Tanzania, Malawi, and South Africa, regions known for early human activity.

The fossils belonged to animals with modern relatives still living near those sites today. The team analyzed bones from rodents (mouse, ground squirrel, gerbil) as well as larger animals, including an antelope, a pig, and an elephant. Thousands of metabolites were identified, many of which closely matched those found in living species.

Health Diet and Disease Written in Bone

Many of the detected metabolites reflected normal biological processes, such as the breakdown of amino acids, carbohydrates, vitamins, and minerals. Some chemical markers were linked to estrogen-related genes, indicating that certain fossilized animals were female.

Other molecules revealed signs of illness. In one striking case, a ground squirrel bone from Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, dated to about 1.8 million years ago, showed evidence of infection by the parasite that causes sleeping sickness in humans. The disease is caused by Trypanosoma brucei and spread by tsetse flies.

“What we discovered in the bone of the squirrel is a metabolite that is unique to the biology of that parasite, which releases the metabolite into the bloodstream of its host. We also saw the squirrel’s metabolomic anti-inflammatory response, presumably due to the parasite,” said Bromage.

Tracing Ancient Diets and Environments

The chemical evidence also revealed what plants the animals consumed. Although plant metabolite databases are far less complete than those for animals, the researchers identified compounds linked to regional plants such as aloe and asparagus.

“What that means is that, in the case of the squirrel, it nibbled on aloe and took those metabolites into its own bloodstream,” explained Bromage. “Because the environmental conditions of aloe are very specific, we now know more about the temperature, rainfall, soil conditions, and tree canopy, essentially reconstructing the squirrel’s environment. We can build a story around each of the animals.”

These reconstructed habitats align with previous geological and ecological research. For example, Olduvai Gorge Bed in Tanzania has been described as freshwater woodland and grassland, while the Upper Bed reflects drier woodlands and marshy areas. Across all studied locations, the fossil evidence consistently points to climates that were wetter and warmer than today.

“Using metabolic analyses to study fossils may enable us to reconstruct the environment of the prehistoric world with a new level of detail, as though we were field ecologists in a natural environment today,” said Bromage.

Research Team and Support

Additional study authors include Bin Hu, Sher Poudel, Sasan Rabieh, and Shoshana Yakar of NYU College of Dentistry; Thomas Neubert, Christopher Lawrence de Jesus, and Hediye Erdjument-Bromage of NYU Grossman School of Medicine; along with collaborators from institutions in France, Germany, Canada, and the United States. The research was supported by The Leakey Foundation, with additional support for the scanning electron microscope provided by the National Institutes of Health (S10 OD023659 and S10 RR027990).