Early humans may have begun butchering elephants 1.8 million years ago

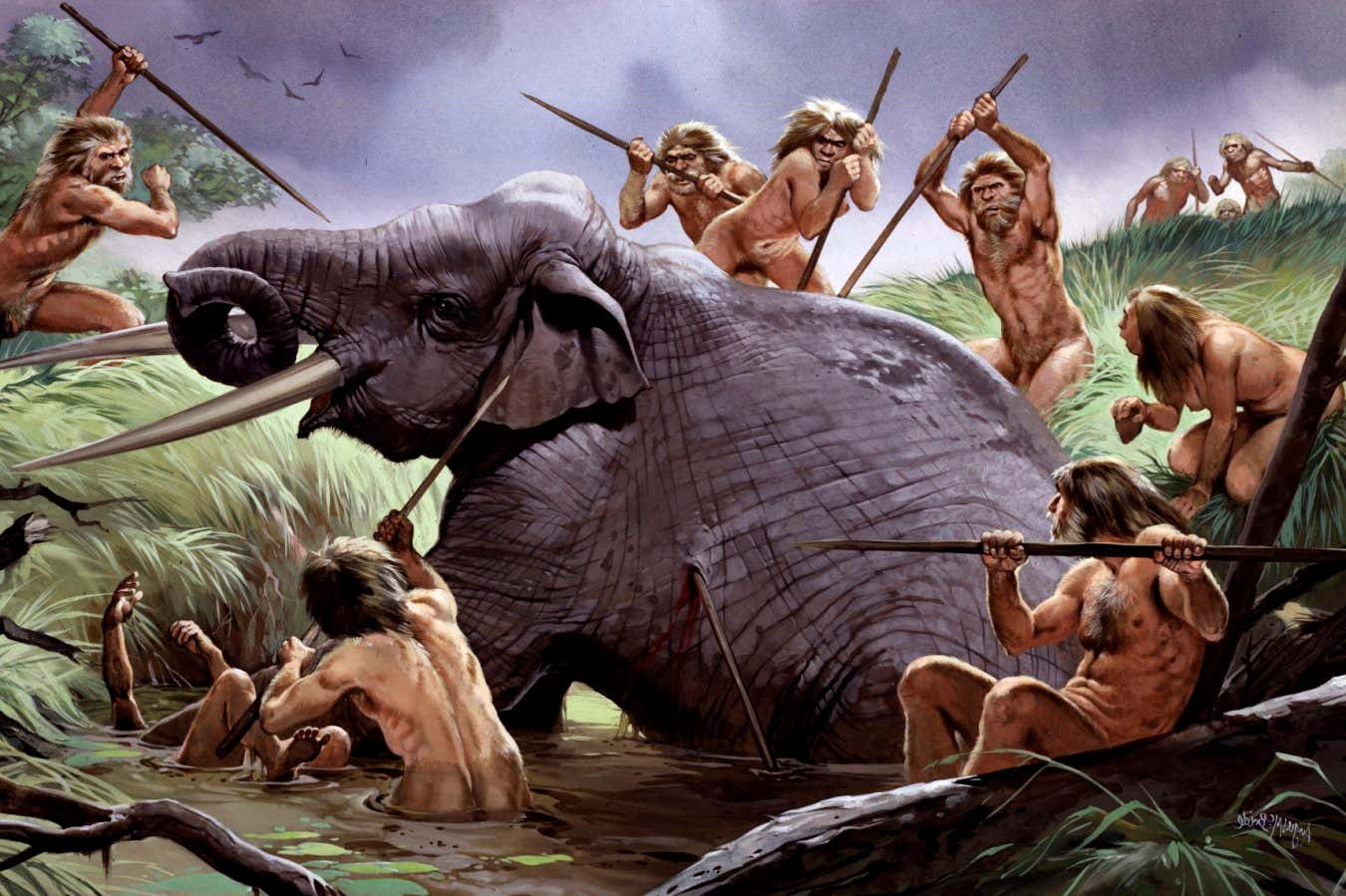

Ancient humans taking on an elephant – our ancestors may have begun butchering the animals 1.8 million years ago

Ancient humans taking on an elephant – our ancestors may have begun butchering the animals 1.8 million years ago

NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM, LONDON/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Butchering an elephant is an extraordinarily difficult feat, requiring serious tools and cooperation, with the reward being a protein bonanza.

Now a team of researchers led by Manuel Domínguez-Rodrigo at Rice University in Texas say that ancient humans may have achieved this milestone 1.78 million years ago at Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania.

“At about 2 million years ago humans were systematically consuming animals like gazelles or waterbucks, but not bigger game,” says Domínguez-Rodrigo.

A little later, evidence from Olduvai Gorge hints that things changed. The gorge is rich in animal and hominin fossils that formed between about 2 million and 17,000 years ago, and at approximately 1.8 million years ago there is a sudden change in the type of animal bones preserved, with remains of elephants and hippos becoming much more abundant. Even so, proving they had been butchered by humans remained difficult, he says.

Then, in June 2022, Domínguez-Rodrigo and his colleagues discovered what appears to be an ancient elephant butchery site at Olduvai.

The site, which they named the EAK site, consisted of the partial skeleton of an extinct elephant species called Elephas recki, surrounded by large numbers of stone tools of a type much larger and more heavy-duty than the stone tools that had been used by hominins before the 2 million year mark. These new tools, says Domínguez-Rodrigo, were likely manufactured by an ancient human called Homo erectus.

“They include Pleistocene knives that are as sharp when we excavated them as they were when [ancient] humans used them.”

Domínguez-Rodrigo and his colleagues think that the stone tools were used to butcher the elephant. Some of the large limb bones seem to have been broken shortly after the elephant’s death, while the bones were still fresh – or “green”. Scavengers like hyenas could have torn flesh from the carcasses, but they are unable to break the shafts of adult or almost adult elephant bones, he says.

“We documented a couple of such bones in our site bearing green fractures, thereby showing that humans had broken them using hammerstones,” he says. “These green broken bones are abundant across the landscape sampled 1.7 million years ago and also bear frequently percussion marks associated with them.”

There is, however, little evidence of the scratches – or cut marks – that butchery can sometimes leave on bones when meat is removed.

What is not known is whether humans killed the elephant or just stumbled across the carcass and opportunistically took advantage of it.

“The only secure thing that we can say is that they butchered it, or part of it, and in the process left a few tools with its bones,” says Domínguez-Rodrigo.

He adds that the transition to butchering elephants was not simply due to the invention of better stone tools but also a sign that hominin groups were beginning to grow larger, resulting in social and cultural changes.

But Michael Pante at Colorado State University is not convinced by the research.

The evidence that this individual elephant was exploited by human ancestors is weak, says Pante. This is because the interpretation relies on the stone tools and the elephant bones being close together and the presence of fractures interpreted to have been made by human ancestors seeking marrow, says Pante.

Pante argues that the earliest definitive evidence for butchery of hippos, giraffes and elephants at Olduvai Gorge comes 80,000 years later at a 1.7-million-year-old site he and his colleagues analysed, named HWK EE.

“Unlike the EAK site the bones of these taxa [at the HWK EE site] have cut marks and are in association with thousands of other bones and artifacts in archaeological context,” he says.

Discovery Tours: Archaeology and palaeontology

New Scientist regularly reports on the many amazing sites worldwide, that have changed the way we think about the dawn of species and civilisations. Why not visit them yourself?

Topics: