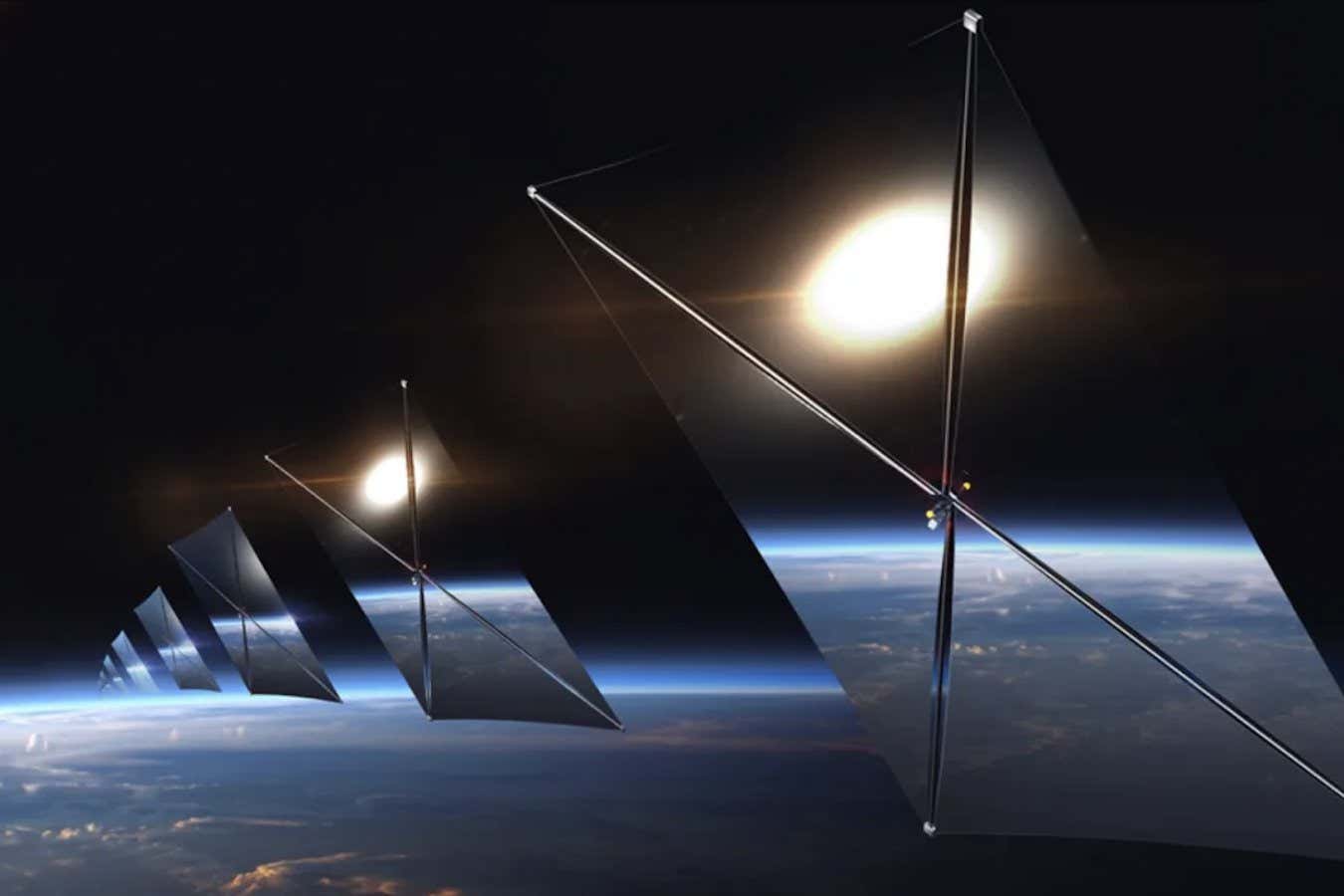

Controversial satellites launching in 2026 will reflect light to Earth

Artist’s rendering of the Reflect Orbital satellites Reflect Orbital A controversial scheme will begin to reflect sunlight to Earth

Artist’s rendering of the Reflect Orbital satellites

Reflect Orbital

A controversial scheme will begin to reflect sunlight to Earth with satellites next year, so that dark places can be temporarily lit for visibility or energy production. But astronomers are sceptical about the plan’s efficacy and possible scientific consequences.

US company Reflect Orbital, which aims to provide “sunlight on demand”, intends to launch its first satellite as soon as early 2026, beaming sunlight to 10 locations as part of an initial “World Tour”. The company then plans to launch thousands of satellites, equipped with mirrors spanning tens of metres, so that light can be reflected to Earth for “remote operations, defense, civil infrastructure, and energy generation.”

By 2030, Reflect Orbital says it will have sufficient satellite coverage to beam 200 watts per square metre to solar farms on Earth, equivalent to levels of sunlight at dusk and dawn, so places with less natural sunlight can still generate reliable energy.

But according to specifications of the company’s first satellite in filings with the US Federal Communications Commission (FCC), the useful light reflected to Earth will be much less than that.

John Barentine at Dark Sky Consulting, a company based in Tucson, Arizona, and astronomers from the American Astronomical Society, used the FCC filing to calculate how much power the satellite would generate from solar panels on Earth. “For a single reflector, the amount of light that’s delivered at ground level is vastly insufficient to power solar farms,” he says.

The level of light would be equivalent to four times the full moon, which over a large surface area wouldn’t generate much electricity, says Barentine. To produce more light than this would require satellites with thousands of reflectors in total, which would be extremely expensive to launch and complex to fly in formation.

However, the satellites could pose problems for astronomers by causing momentary flashes of sunlight when their mirrors change position, says Barentine. Some scattering and dissipation of light in the atmosphere, sending it towards unintended locations, is unavoidable, especially if the satellite’s reflectors are damaged by micrometeorites and become imperfect reflectors, he says.

Reflect Orbital has contacted scientists to discuss potential mitigations for these issues, says Barentine. Reflect Orbital did not respond to an interview request from New Scientist.

Topics: