Can Trump’s shattered plan be glued back together?

AFP via Getty Images Akilimali Mirindi is one of thousands who have fled the recent upsurge in fighting The

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesThe US ambassador to the UN has accused Rwanda of leading Africa’s Great Lakes region toward war, just over a week after a peace deal was signed in Washington to end the decades-long conflict.

US President Donald Trump Trump hailed the deal between DR Congo’s President Félix Tshisekedi and Rwanda’s President Paul Kagame as “historic” and “a great day for Africa, great day for the world”.

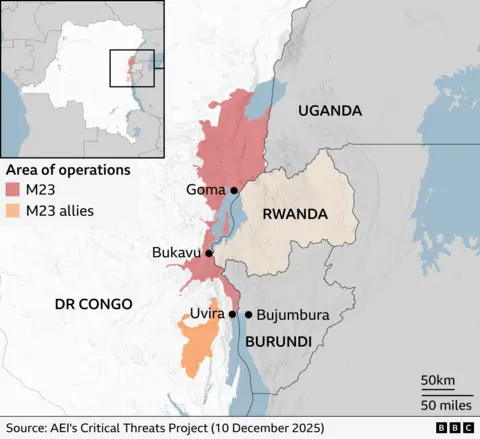

But the M23 rebel group says it has “fully liberated” the key city of Uvira in an offensive the US and European powers say is backed by Rwanda. UN experts have previously accused it of having “de facto control” of the rebel force’s operations.

Rwanda denies the allegations, however, its presence in Washington was a tacit acknowledgment of its influence over the M23.

The rebels were not signatories to Trump’s deal – and have been taking part in a parallel peace process led by Qatar, a US ally.

The latest fighting risks further escalating an already deeply complex conflict.

Why did the M23 seize Uvira now?

Prof Jason Stearns, a Canada-based political scientist who specialises in the region, told the BBC that the view in M23 circles was that “they need more leverage in the negotiations”, while the feeling in the Rwandan government is that Tshisekedi cannot be trusted.

He added that the assault on Uvira, in South Kivu province, “flies in the face of all the negotiations that are under way”.

“It appears to humiliate the US government. I’m not sure what strategic purpose that would serve,” Prof Stearns told the BBC.

The M23’s new offensive in South Kivu started a few days before Kagame and Tshisekedi flew to Washington last week to ratify the agreement first hammered out in June.

Bram Verelst, a Burundi-based researcher with the Institute for Security Studies (ISS) think-tank, said the assault appeared to be an attempt to force Burundi to withdraw the troops it had in eastern DR Congo backing the army against the rebel forces and Rwanda.

He pointed out that Uvira – which lies just 27km (17 miles) from Burundi’s capital, Bujumbura, on the northern tip of Lake Tanganyika – was of strategic importance because of the presence of at least 10,000 Burundian troops in South Kivu.

“Uvira is Burundi’s gateway into eastern DR Congo, to send troops and supplies. That has now been cut off,” Mr Verelst told the BBC.

“It seems that many Burundian troops are withdrawing, but it’s not clear if all contingents will retreat,” he added.

Yale Ford, an Africa Analyst for the Critical Threats Project at the American Enterprise Institute, pointed out that Uvira, which had a population of about 700,000, was the DR Congo government’s last major foothold and military hub in South Kivu.

He added that the M23 was now likely to establish a parallel administration in the city, and use its military gains “as a bargaining chip in peace talks”.

As for the DR Congo government, it has not acknowledged its latest military setback, but says that the “gravity of the situation is compounded by the now proven risk of regional conflagration”.

What does it mean for Burundi?

Burundi has been a natural ally of DR Congo for years because of its enmity with Rwanda.

Both accuse the other of backing rebel groups seeking to overthrow their respective governments.

The neighbours share a similar language and ethnic make-up – with Tutsi and Hutu communities often vying for power – and both have suffered terrible ethnic-based massacres.

But unlike Rwanda, which is headed by a Tutsi president, the majority Hutus are in power in Burundi.

Burundi’s government fears that if the M23 cements its presence in South Kivu, it would strengthen a Burundian rebel group called Red Tabara.

Based in South Kivu, it is mainly made up of Tutsis – and has attacked Burundi in the past.

In an apparent attempt to placate Burundi’s fears, the M23 said it had “no sights beyond our national borders”.

“Our fight has the objective of peace, the protection of the population, the rebuilding of the state in DR Congo, as well as the stability of the Great Lakes region,” the group added.

Burundi has shut its border with DR Congo, but, according to Mr Verelst, it is still allowing people to cross into its territory after carrying out security checks.

Aid agencies say that about 50,000 people have fled into Burundi in the past week.

Burundian troops – along with the Congolese army and allied militias – fought to block the rebel advance towards Uvira, but the city itself fell “without much fighting”, Mr Verelst said.

The fall of Uvira would hit Burundi’s already struggling economy as the country has been suffering from a severe shortage of foreign currency and fuel, and had been heavily dependent on eastern DR Congo for both, he said.

How did the M23 manage to capture Uvira?

The M23 began a major advance earlier this year when it captured Goma, the capital of North Kivu province, on the border with Rwanda.

At the time, South African troops were deployed to help DR Congo’s army, but they were forced to withdraw after the M23 seized the city in January.

Shortly afterwards the rebels captured the next big city in eastern DR Congo, Bukavu, capital of South Kivu.

The move on Uvira came after the rebels broke the defence lines of the DR Congo army, militias allied with it and Burundian troops.

Prof Stearns said the M23 was estimated to have more than 10,000 fighters, but there was likely to have been an “influx” of Rwandan troops for the recent offensive to capture Uvira.

“The reason why they are able to defeat their enemy is that the Rwandan army, at least, is very disciplined, and I think discipline matters more than manpower,” he said.

“The conflict in recent days has also featured the extensive use of drone technology on both sides but the Rwandans have used this more to their advantage than the Congolese,” he added.

Where does this leave the peace process?

It appears to be in deep trouble.

The US ambassador to the UN blamed Rwanda for the recent fighting.

“Instead of progress toward peace, as we have seen under President Trump’s leadership in recent weeks, Rwanda is leading the region toward more instability and toward war,” Mike Waltz told a Security Council meeting.

An earlier statement – issued by the US, European Union, and eight European governments – went further, saying that both the M23 and the Rwanda Defence Force (RDF) should immediately halt “offensive operations”, and Rwandan troops should withdraw from eastern DR Congo.

Prof Stearns said the policy experts he had spoken to were “baffled” by the timing of the move to capture Uvira.

“It was literally as they were signing a peace deal in Washington that Rwandan troops were amassing, and then invaded the area around Kamanyola, which is across the border from Rwanda, and then advanced on Uvira,” he added.

Rwanda’s foreign ministry has not responded to the claims that its troops were in South Kivu, but said the ceasefire violations and fighting could not be “attributed” to Rwanda.

It accused the DR Congo and Burundian armies of bombing villages near the Rwandan border, and said Burundi had “amassed” nearly 20,000 troops in South Kivu in support of DR Congo’s army.

It added that it was now clear that DR Congo was “never ready to commit to peace”, and even though Tshisekedi had attended the ceremony in Washington, it was “as if he had been forced to sign” the peace accord.

The DR Congo’s government levelled a similar accusation against Kagame, saying he had made a “deliberate choice” to abandon the Washington Accord, and to undermine Trump’s efforts to end the conflict.

Can the deal be salvaged?

Prof Stearns said the US-led peace process was now on a “troubled path, perhaps it is stuck”.

He pointed out that the success of the deal hinged on DR Congo’s army launching an operation to disarm the FDLR militia group, members of which were involved in the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, and which Kagame’s government sees as a continued threat.

But, Prof Stearns said, he could not see DR Congo’s army launching such an operation at the moment.

The peace deal also envisaged economic co-operation between DR Congo and Rwanda, including on hydro-electric power, mining and infrastructure development – something that the US hopes would pave the way for American companies to increase investments in the mineral-rich region.

Prof Stearns said he could not see this happening either while Rwandan troops remained in eastern DR Congo, and fighting continued.

He added that his understanding was that the parallel peace process in Doha – led by Qatar’s government to broker a peace deal between the M23 and DR Congo’s government – was also on hold at the moment.

“It’s very difficult to imagine the Congolese returning there right now after there has been this major offensive by the M23,” he added.

What are Tshisekedi’s options?

Prof Stearns said that Tshisekedi was under “very serious” pressure from the public for his failure to keep his numerous promises to bring an end to the fighting in the east.

He said Tshisekedi might also be under pressure from parts of the army, with whom he had a strained relationship after the arrest of generals for alleged corruption and because of the setbacks in the east.

He added that Tshisekedi was banking on the US to put pressure on Rwanda to withdraw its support for the M23.

“It’s going to be very difficult for the Congolese army to muster a response.

“It’s now in the hands of the various peace brokers, the US in particular, and perhaps Qatar and other donors,” the academic said.

“It’s to be seen how much they care about ending this conflict, and how much political capital they are willing to spend.”

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC