Boosting the glymphatic system: What to do to help detox your brain

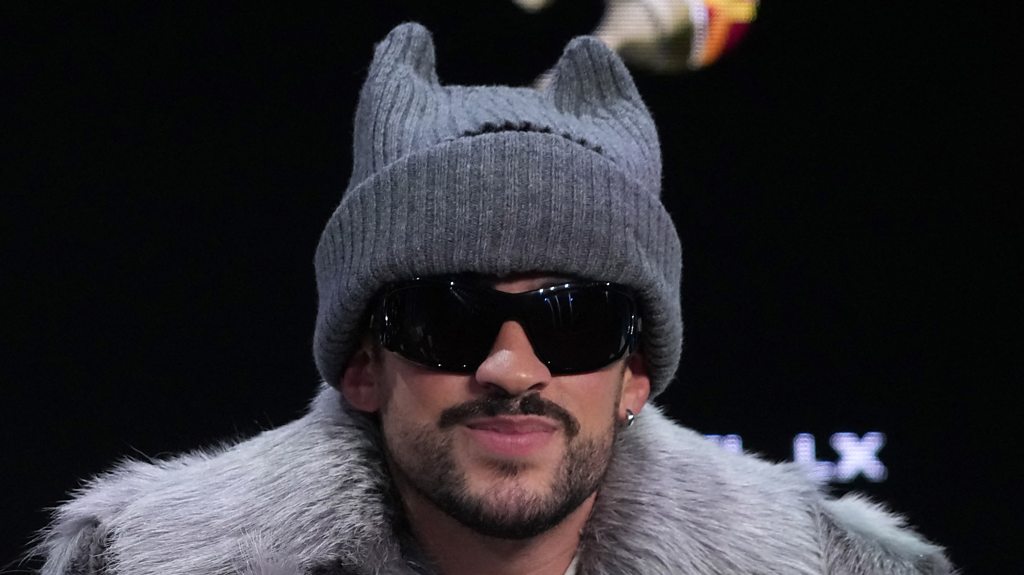

When neurons are active in your brain they create waste products Nick Veasey/Science Photo Library/Alamy As we enjoy ourselves

When neurons are active in your brain they create waste products

Nick Veasey/Science Photo Library/Alamy

As we enjoy ourselves through the festive season, many will already be planning a detox in the new year: cutting back on screentime, perhaps, or abstaining from alcohol. Recently, I wondered whether you could apply the same logic to the brain – is there anything I can do once the fun is over to help clear away my cognitive cobwebs?

In fact, the brain performs its own kind of detox every day – clearing out the waste products generated by metabolism that would otherwise build up and cause damage. But can we help this process along? And if so, might that protect us from age-related cognitive decline and dementia?

Let’s start by meeting the brain’s cleaning crew, beginning with the glymphatic system. This relatively recently discovered waste-removal pathway “sucks out” unwanted proteins and other waste debris from the spaces between your neurons and transports it to the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

“The CSF circulates much like water in a dishwasher,” says Maha Alattar at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond.

The fluid then discharges the waste products into your lymph nodes and from there to the veins, before they are eventually excreted from your body.

How the glymphatic and lymphatic systems connect isn’t particularly well understood, but researchers are increasingly interested in how to optimise the glymphatic system’s efficiency because they think it might prove important for preventing cognitive decline and sustaining healthy ageing. This is in part because a build-up of metabolic waste in the brain is associated with poorer cognitive health, increased risk of dementia and accelerated symptoms of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

“The glymphatic system is exciting,” says Nandakumar Narayanan at University of Iowa Health Care. “There are lots of great ideas and research efforts to understand the glymphatic system, measure it rigorously, and use these measurements to better understand human health and disease.”

Boosting your brain’s waste removal system

So can we do anything to make this waste removal system run more efficiently? Recent studies have hinted that lifestyle factors may be our best tools.

“The most well-established way to enhance glymphatic clearance is sleep,” says Lila Landowski at the University of Tasmania in Hobart, Australia.

The glymphatic system is largely disengaged during our waking hours and does its best work during the night. For instance, in mice, CSF flow increases by around 60 per cent during sleep, significantly enhancing the removal of beta amyloid – the protein associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

While trials haven’t yet definitely proved that boosting the glymphatic system prevents dementia “the hypothesis is supported by the fact that factors which reduce glymphatic clearance − disordered sleep, glymphatic dysfunction, and being sedentary − are all linked to increased risk of neurodegenerative disease and impaired cognition,” says Landowski.

Intriguingly, how you sleep might also help with glymphatic drainage. In 2015, Helene Benveniste, now at Yale School of Medicine, and her colleagues found that side-sleeping improved glymphatic clearance in mice more efficiently than sleeping on the back or front. No one has yet tested this in humans, but because many kinds of dementia are strongly linked with sleep disturbances, Benveniste and her team propose that the way you sleep might turn out to be a helpful part of our armoury against dementia.

Other ways to drain your brain

Growing evidence suggests that other lifestyle factors, such as exercise, also boost glymphatic function. In April, 37 adults underwent brain imaging before and after participating in either a single workout, or a 12-week regime of stationary cycling, involving 30-minute sessions three times a week. Only the group that exercised for 12 weeks showed an increase in glymphatic drainage.

“Studies in mice show that glymphatic clearance approximately doubles after 5 weeks of exercise compared to sedentary mice,” says Landowski, “but shorter timeframes haven’t yet been studied in humans.”

But a closer look at the glymphatic system may reveal other ways to enhance its flow. Lymphatic vessels that drain the CSF are deep in the neck, which make them hard to manipulate directly, but recently Gou Young Koh at the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology in South Korea and his colleagues have found another network of lymph vessels just below the skin on the face and neck of monkeys and mice.

In mice, gently stroking downward along the face and neck for one-minute increased CSF flow threefold – effectively restoring the reduced flow seen in older animals to a more youthful state.

Similar vessels have been found in human cadavers, raising the possibility that a facial or neck massage might boost CSF flow in us too, and in doing so help with glymphatic clearance, but more research is necessary to identify whether it happens and whether this increased flow can protect against neurodegenerative disease.

The strong evidence for yogic breathing

One type of exercise you don’t want to overlook is yogic breathing, says Hamid Djalilian at the University of California, Irvine. There is now well-documented evidence that diaphragmatic breathing can increase CSF velocity, which Djalilian says is enough to trigger the glymphatic “rinse cycle”.

Diaphragmatic breathing is a deep breathing technique in which you inhale through the nose while moving your belly outwards to move your diaphragm down while the chest stays relatively still. Exhaling through pursed lips while moving the belly back inwards finishes the cycle.

Unexplored potential

However, despite enthusiasm from some researchers, our understanding of the intricate workings of the glymphatic system is still in its infancy, and not everyone thinks we know enough yet to actively prescribe interventions. “We are definitely not to the level that we can predict how specific interventions such as exercise affect the glymphatic system. There are a few studies in mice and small groups of humans, but not a large definitive study,” cautions Narayanan.

But even he is optimistic. “The potential is huge − but we need to do these studies carefully and rigorously.”

So, for now, I’ll concentrate on the things I should be doing anyway – sleeping well and exercising regularly. These habits are already important for general health, but if glymphatic research bears out, they may prove even more important for keeping my brain clear not only in the new year, but well into the future.

Topics: