A superfluid freezes and breaks the rules of physics

When everyday matter is cooled, it follows a familiar path. A gas becomes a liquid, and with further cooling,

When everyday matter is cooled, it follows a familiar path. A gas becomes a liquid, and with further cooling, that liquid turns into a solid. Quantum matter does not always follow these rules. More than a century ago, scientists discovered that helium behaves in an unexpected way at extremely low temperatures. Instead of freezing, it transforms from a normal gas into a superfluid, a rare state of matter that flows without any resistance and displays strange behaviors, including creeping up the sides of containers.

Physicists have long wondered what would happen if a superfluid were cooled even further. Despite decades of effort, that question remained unanswered for nearly 50 years.

A Superfluid That Comes to a Halt

In new research published in Nature, a team led by physicists Cory Dean of Columbia University and Jia Li of the University of Texas at Austin reports a striking result. They observed a superfluid, which typically remains in constant motion, suddenly stop moving. “For the first time, we’ve seen a superfluid undergo a phase transition to become what appears to be a supersolid,” said Dean. The change is comparable to water freezing into ice, but taking place in the quantum realm.

What Is a Supersolid?

A classical solid is defined by atoms locked into a rigid, repeating crystal structure. A supersolid is the quantum version of this idea. It is predicted to have an ordered, solid-like arrangement while also retaining properties normally associated with liquids, including frictionless flow. This combination makes supersolids one of the most unusual states of matter proposed by physics.

Until now, however, no experiment had clearly shown a superfluid naturally transforming into a supersolid. This includes helium and all other known forms of matter. Some laboratory demonstrations have mimicked supersolids using highly controlled setups created by atomic, molecular, and optical (AMO) physicists. These experiments rely on lasers and optical components to form a periodic trap that forces particles into a repeating pattern, similar to how Jello takes shape inside an ice cube tray.

Turning to Graphene for Answers

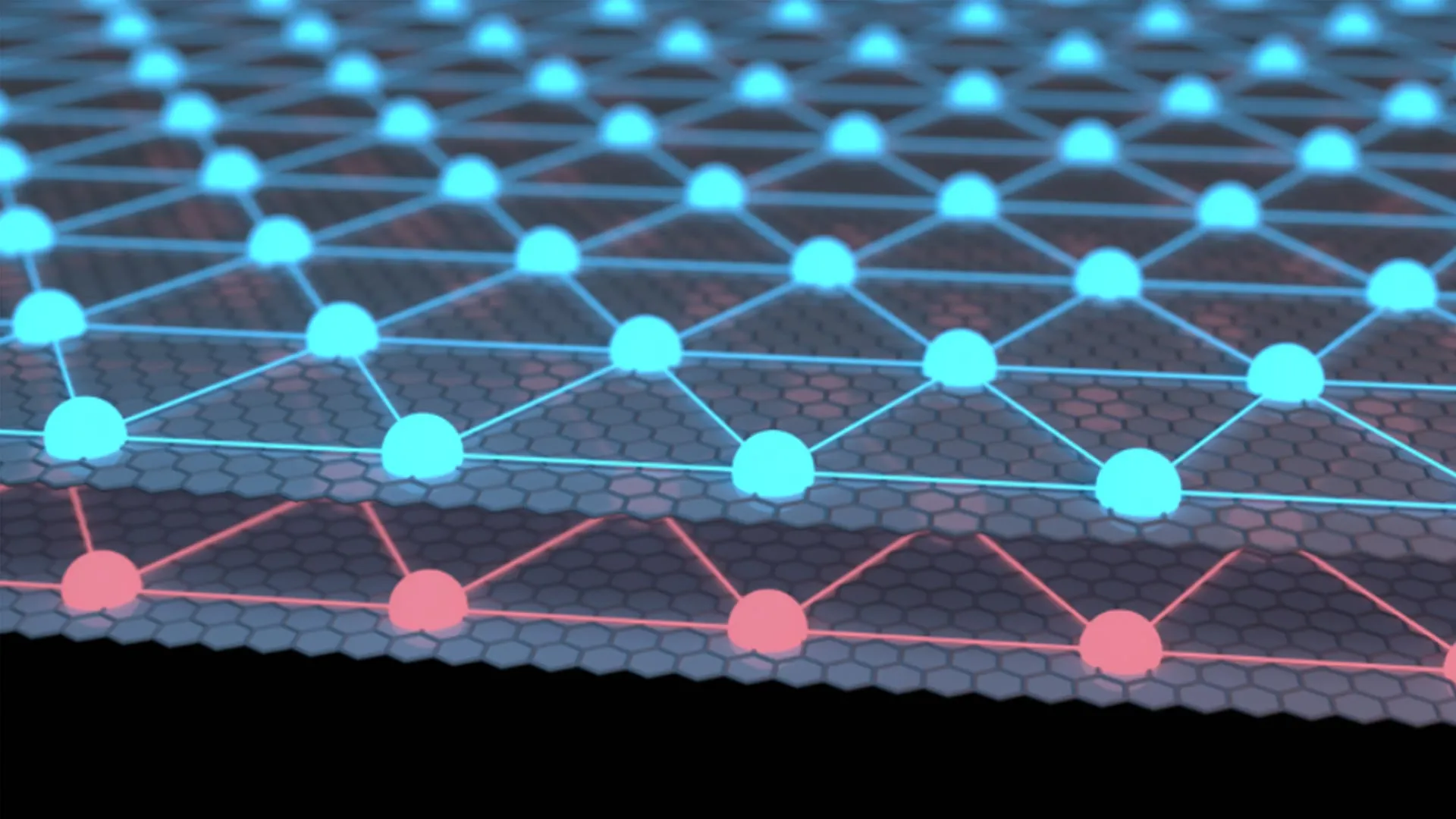

A supersolid that forms on its own, without artificial confinement, has remained one of the most debated mysteries in condensed matter physics. Dean’s team took a different approach by working with graphene, a naturally occurring material made of a single layer of carbon atoms. The group included Li, who conducted the work while he was a postdoc at Columbia, and Yihang Zeng (now an assistant professor at Purdue University), a former PhD student in the group.

Graphene can support particles known as excitons. These quasiparticles appear when two atom-thin graphene sheets are stacked together and tuned so that one layer contains extra electrons while the other contains extra holes (which are left behind when electrons leave the layer in response to light). Because electrons carry a negative charge and holes act as positive charges, the two can bind together to form excitons. Under a strong magnetic field, these excitons can behave collectively as a superfluid.

A Surprising Phase Change in a 2D Material

Two-dimensional materials like graphene are powerful tools for studying quantum behavior because their properties can be carefully adjusted. Researchers can control factors such as temperature, electromagnetic fields, and even the spacing between layers. As Dean’s team tuned these parameters, they noticed an unexpected pattern linking exciton density and temperature.

When excitons were densely packed, they flowed freely as a superfluid. As the density dropped, the flow stopped entirely, and the system became an insulator. Raising the temperature restored the superfluid behavior. This sequence ran counter to long-standing assumptions about how superfluidity works.

“Superfluidity is generally regarded as the low-temperature ground state,” said Li. “Observing an insulating phase that melts into a superfluid is unprecedented. This strongly suggests that the low-temperature phase is a highly unusual exciton solid.”

Is It Truly a Supersolid?

Whether this state fully qualifies as a supersolid remains an open question. “We are left to speculate some, as our ability to interrogate insulators stops a little,” explained Dean — their expertise is in transport measurements, and insulators don’t transport a current. “For now, we’re exploring the boundaries around this insulating state, while building new tools to measure it directly.”

What Comes Next for Supersolids

The team is now investigating other layered materials that could host similar quantum phases. In bilayer graphene, the excitonic superfluid and likely supersolid only appear under strong magnetic fields. Other materials are harder to fabricate in the required configurations, but they may allow excitons to remain stable at higher temperatures and without the need for a magnetic field.

Being able to control superfluids in two-dimensional materials could have far-reaching implications. Compared to helium, for example, excitons are thousands of times lighter, so they could form exotic quantum states at much higher temperatures. While supersolids are still not fully understood, these findings provide strong evidence that 2D materials will play a central role in uncovering how this strange quantum phase works.