A new study casts doubt on life beneath Europa’s ice

Jupiter has nearly 100 known moons, but Europa continues to stand out as one of the most compelling. Beneath

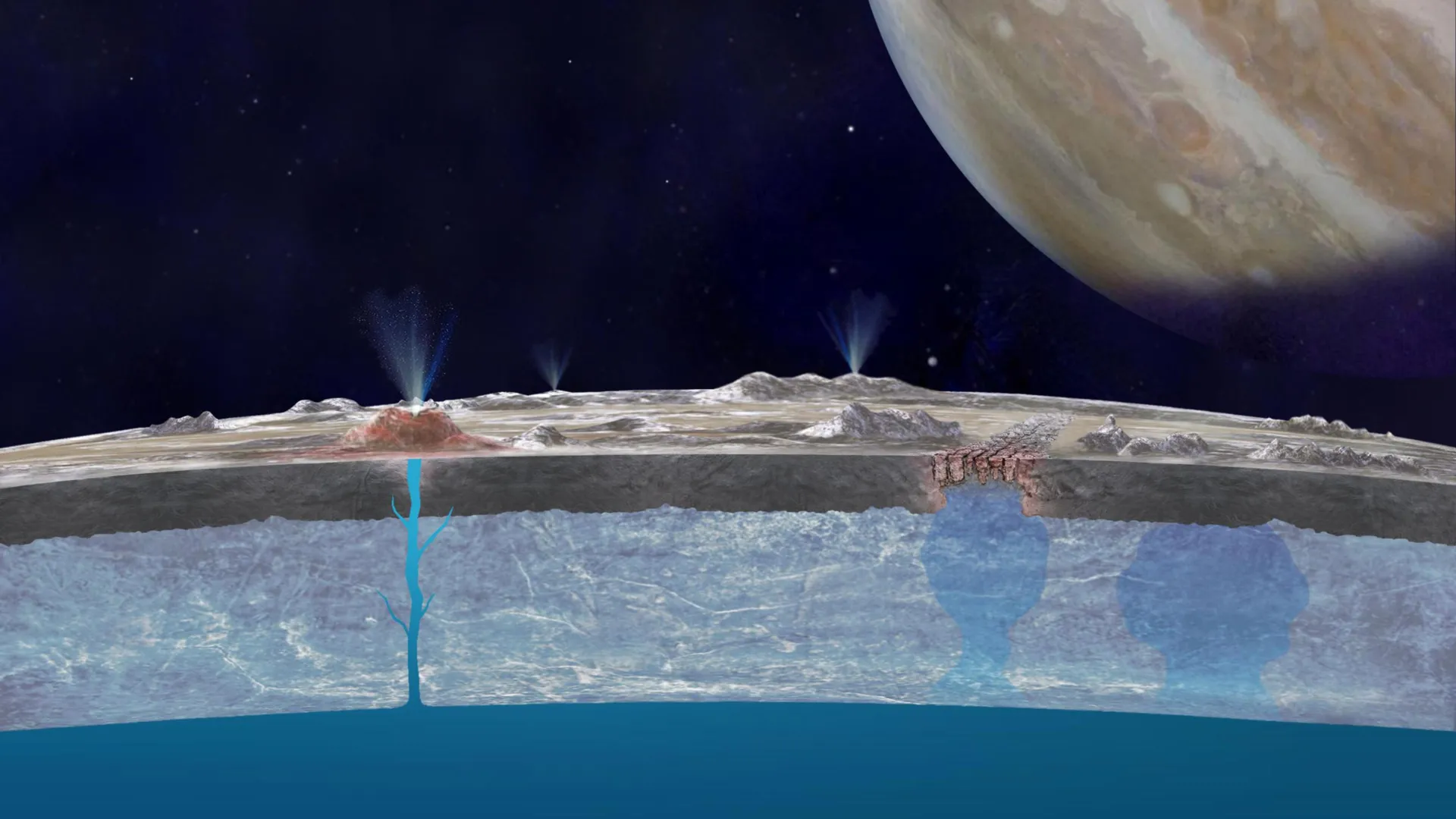

Jupiter has nearly 100 known moons, but Europa continues to stand out as one of the most compelling. Beneath its thick shell of ice, scientists believe the moon contains an enormous ocean of salty liquid water. That possibility has fueled decades of speculation about whether Europa could host life, placing it among the most important targets for exploration in the solar system.

New research led by Paul Byrne, an associate professor of Earth, environmental, and planetary sciences, challenges one of the central hopes surrounding Europa. The study suggests that while the moon has an ocean, its seafloor may not have the geological activity needed to support life. By modeling Europa’s size, internal structure, and the gravitational pull exerted by Jupiter, Byrne and his colleagues found little evidence for tectonic movement, hydrothermal vents, or other energy sources typically linked to habitable environments on the ocean floor.

“If we could explore that ocean with a remote-control submarine, we predict we wouldn’t see any new fractures, active volcanoes, or plumes of hot water on the seafloor,” Byrne said. “Geologically, there’s not a lot happening down there. Everything would be quiet.” On a frozen world like Europa, he added, that lack of activity could point to an ocean without life.

The study was published in Nature Communications. Co-authors from the Department of Earth, Environmental, and Planetary Sciences include Professor Philip Skemer, associate chair of the department; Professor Jeffrey Catalano; Douglas Wiens, the Robert S. Brookings Distinguished Professor; and graduate student Henry Dawson. Byrne, Skemer, Catalano, Wiens, and Dawson are also affiliated with the McDonnell Center for the Space Sciences.

Why Europa’s Seafloor Matters to Scientists

For Byrne, Europa’s scientific appeal goes beyond the question of habitability. “I’m really interested to know what that seafloor looks like,” he said. “For all of the talk about the ocean itself, there has been little discussion about the seafloor.”

Because no spacecraft has yet reached Europa’s ocean, the research team relied on a combination of existing measurements and comparisons with Earth, the Moon, and other planetary bodies to estimate what conditions might be like beneath the ice.

Ice Shell Thickness and Ocean Depth

Scientists estimate that Europa’s icy outer layer is between 15 and 25 km thick. Below that ice lies a global ocean that may reach depths of up to 100 km. Despite being slightly smaller than Earth’s Moon, Europa is believed to contain far more water than Earth itself.

Under the ocean sits a rocky core similar in composition to Earth’s. However, unlike Earth’s still-hot interior, Europa’s core likely cooled long ago. Byrne and his co-authors calculated that any internal heat would have dissipated billions of years in the past.

Jupiter’s Gravity and Tidal Heating Limits

The researchers also examined how Jupiter’s gravity affects Europa. Strong tidal forces can generate heat inside a moon, keeping it geologically active. This effect is dramatic on Io, Jupiter’s innermost large moon, where intense gravitational stretching drives constant volcanic eruptions. Io’s orbit regularly brings it closer to Jupiter, amplifying those tidal forces and making it the most volcanically active body in the solar system.

Europa’s orbit, by contrast, is more stable and farther from Jupiter. As a result, the tidal forces acting on Europa are much weaker, reducing their ability to generate heat and drive geological activity, Byrne explained.

“Europa likely has some tidal heating, which is why it’s not completely frozen,” Byrne said. “And it may have had a lot more heating in the distant past. But we don’t see any volcanoes shooting out of the ice today like we see on Io, and our calculations suggest that the tides aren’t strong enough to drive any sort of significant geologic activity at the seafloor.”

According to Byrne, Europa’s lack of seafloor energy makes the presence of current life unlikely. “The energy just doesn’t seem to be there to support life, at least today,” he said.

Future Missions and Lingering Curiosity

Despite the sobering conclusions, Byrne remains enthusiastic about future exploration, particularly NASA’s Europa Clipper mission, which is scheduled to fly past the moon in the spring of 2031. That mission — conceived and championed in part by Bill McKinnon, the Clark Way Harrison Distinguished Professor in Arts & Sciences and interim director of the McDonnell Center for the Space Sciences — will collect detailed images of Europa’s surface and improve measurements of its ice shell and ocean. “Those measurements should answer a lot of questions and give us more certainty,” Byrne said.

Even if future evidence shows that Europa’s ocean is lifeless today, Byrne says the effort will still be worthwhile. “I’m not upset if we don’t find life on this particular moon,” he said. “I’m confident that there is life out there somewhere, even if it’s 100 light-years away. That’s why we explore — to see what’s out there.”