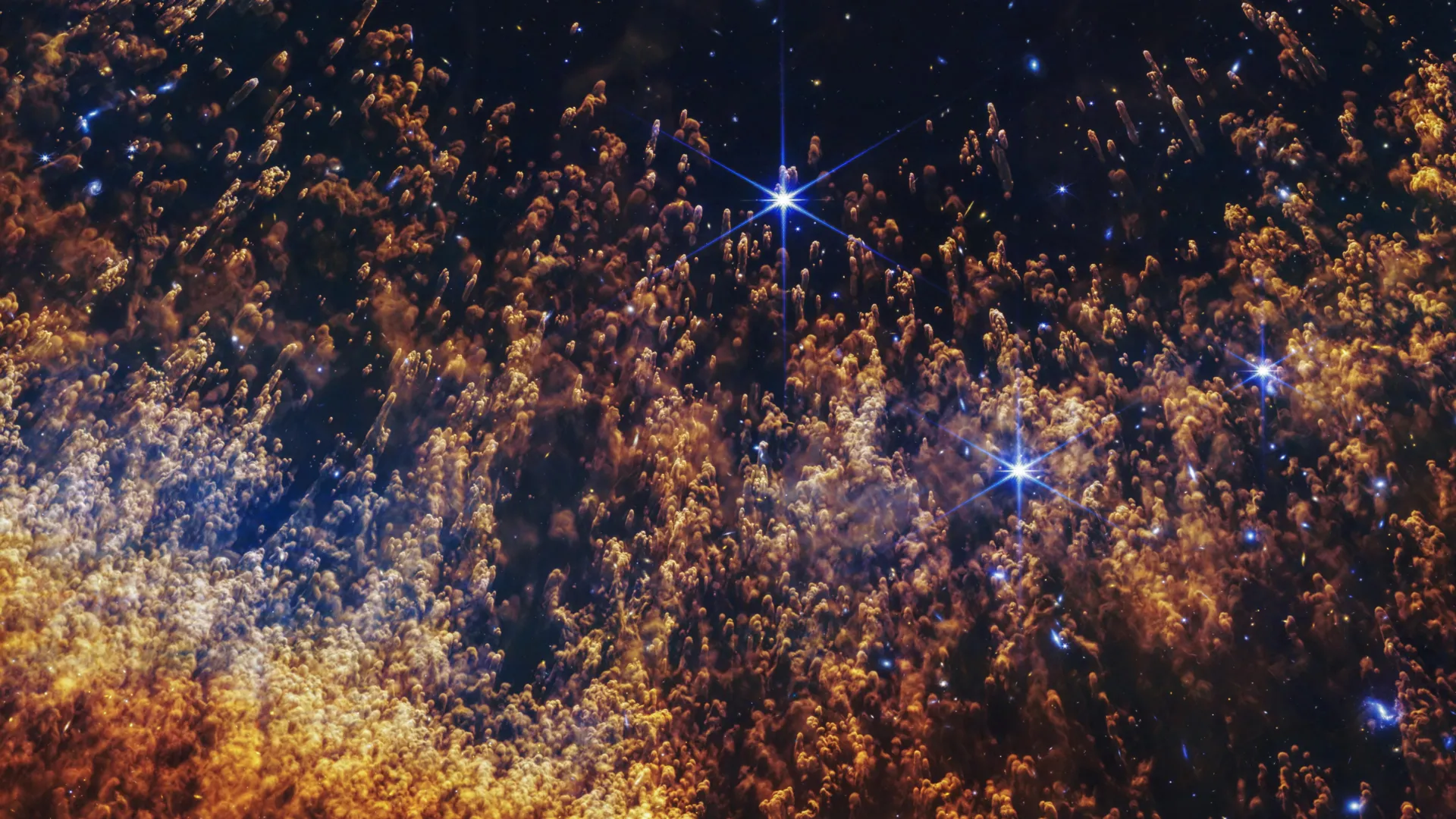

A dying star’s final breath glows in a new Webb image of the Helix Nebula

First observed in the early 1800s, the Helix Nebula has become one of the most recognizable planetary nebulas in

First observed in the early 1800s, the Helix Nebula has become one of the most recognizable planetary nebulas in the sky thanks to its bold, ring-like appearance. As one of the closest planetary nebulas to Earth, it offers astronomers a rare opportunity to closely examine the final stages of a star’s life. For decades, scientists have studied it using both ground-based and space-based telescopes.

Now, the James Webb Space Telescope has taken those observations further by delivering the most detailed infrared view ever captured of this familiar object.

A Preview of the Sun’s Distant Fate

Webb’s powerful instruments allow scientists to zoom deep into the Helix Nebula, offering a glimpse of what could eventually happen to our own Sun and planetary system. The telescope’s sharp infrared vision clearly reveals the structure of gas flowing away from a dying star. This material, once part of the star itself, is being returned to space, where it can later contribute to the formation of new stars and planets.

Images from Webb’s NIRCam (Near-Infrared Camera) reveal dense pillars of gas that resemble comets with long trailing tails. These features outline the inner edge of an expanding shell of material. They form as fast-moving, extremely hot winds from the dying star slam into cooler layers of dust and gas that were released earlier in the star’s life. The collisions carve and sculpt the nebula, creating its intricate and textured appearance.

How Webb’s View Compares to Earlier Observations

Since its discovery nearly two centuries ago, the Helix Nebula has been observed by many telescopes. Webb’s near-infrared images bring small knots of gas and dust into much sharper focus than the soft, glowing view seen in images from the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope. The new data also highlights a clear transition from the hottest gas near the center to much cooler material farther out, as the nebula continues to expand away from its central star.

At the center of the Helix Nebula is a white dwarf, the exposed core left behind after the star shed its outer layers. Although it sits just outside the frame of Webb’s image, its influence is unmistakable. Intense radiation from the white dwarf energizes the surrounding gas, producing a range of environments. Closest to the core is hot, ionized gas, followed by cooler regions rich in molecular hydrogen. Farther out, sheltered pockets within dust clouds allow more complex molecules to begin forming. These regions contain the basic materials that can eventually help build new planets in other star systems.

What the Colors in Webb’s Image Reveal

In Webb’s image, color is used to represent differences in temperature and chemical makeup. Blue tones indicate the hottest gas, energized by strong ultraviolet radiation. Yellow areas show cooler regions where hydrogen atoms bond together to form molecules. Along the outer edges, red hues trace the coldest material, where gas thins and dust begins to take shape. Together, these colors illustrate how a star’s final outflow becomes the raw material for future worlds, adding to Webb’s growing contributions to our understanding of how planets form.

The Helix Nebula lies about 650 light-years from Earth in the constellation Aquarius. Its relative closeness and striking structure have made it a favorite target for both amateur skywatchers and professional astronomers.

More Information About the James Webb Space Telescope

Webb is the largest and most powerful space telescope ever launched. As part of an international collaboration, ESA provided the launch service using the Ariane 5 rocket. ESA also oversaw the development and testing of Ariane 5 modifications for the mission and arranged the launch through Arianespace. In addition, ESA contributed the NIRSpec instrument and 50% of the mid-infrared instrument MIRI, which was designed and built by a consortium of nationally funded European Institutes (The MIRI European Consortium) working in partnership with JPL and the University of Arizona.

Webb is a joint project involving NASA, ESA, and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA).