Core Survey by NASA’s Roman Mission Will Unveil Universe’s Dark Side

The broadest planned survey by NASA’s upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope will reveal hundreds of millions of galaxies

The broadest planned survey by NASA’s upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope will reveal hundreds of millions of galaxies scattered across the cosmos. After Roman launches as soon as this fall, scientists will use these sparkly beacons to study the universe’s shadowy underpinnings: dark matter and dark energy.

“We set out to build the ultimate wide-area infrared survey, and I think we accomplished that,” said Ryan Hickox, a professor at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, and co-chair of the committee that shaped the survey’s design. “We’ll use Roman’s enormous, deep 3D images to explore the fundamental nature of the universe, including its dark side.”

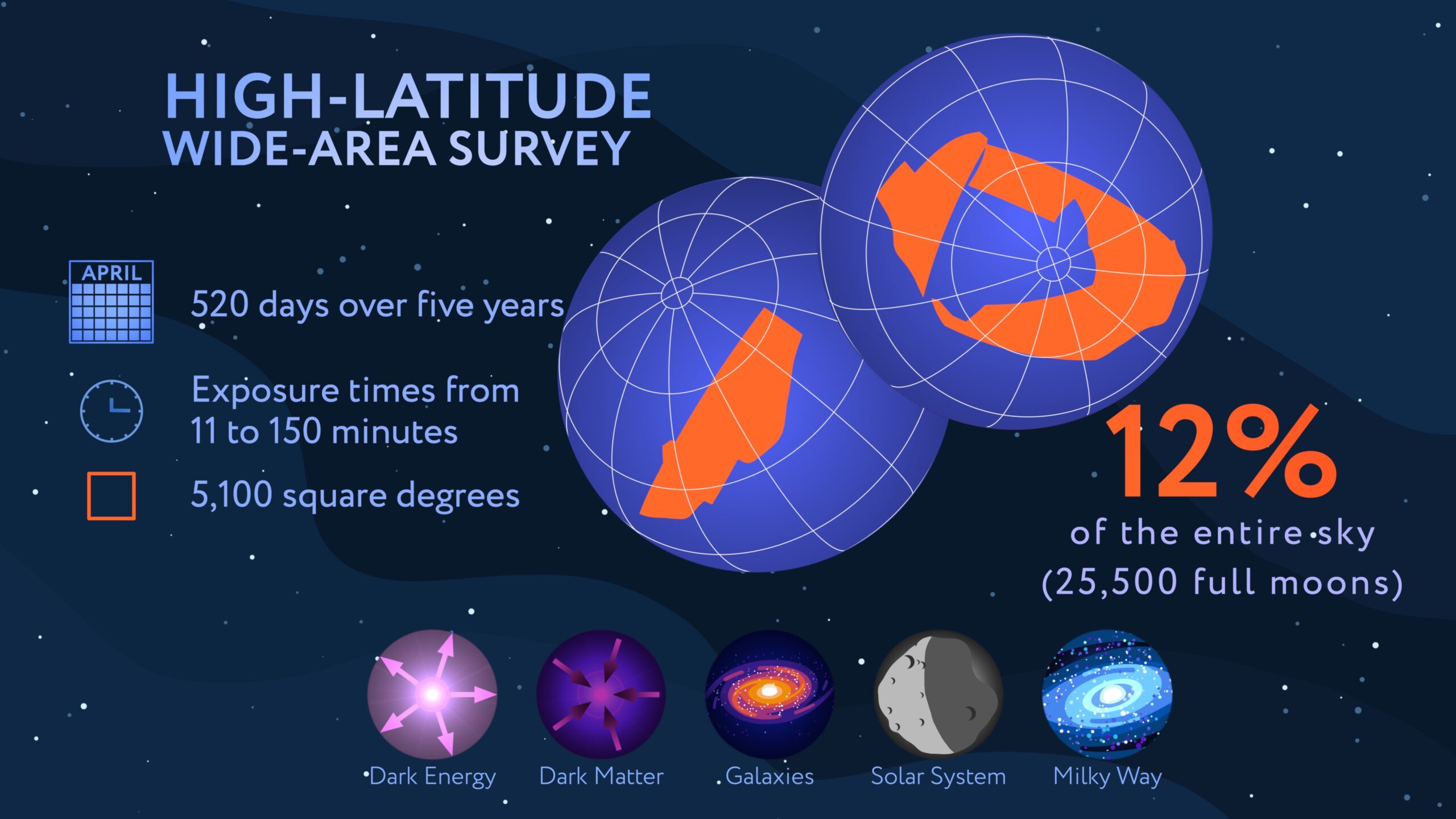

Roman’s High-Latitude Wide-Area Survey is one of the mission’s three core observation programs. It will cover more than 5,000 square degrees (about 12 percent of the sky) in just under a year and a half. Roman will look far from the dusty plane of our Milky Way galaxy (that’s what the “high-latitude” part of the survey name means), looking up and out of the galaxy rather than through it to get the clearest view of the distant cosmos.

“This survey is going to be a spectacular map of the cosmos, the first time we have Hubble-quality imaging over a large area of the sky,” said David Weinberg, an astronomy professor at Ohio State University in Columbus, who played a major role in devising the survey. “Even a single pointing with Roman needs a whole wall of 4K televisions to display at full resolution. Displaying the whole high-latitude survey at once would take half a million 4K TVs, enough to cover 200 football fields or the cliff face of El Capitan.”

The survey will combine the powers of imaging and spectroscopy to unveil a goldmine of galaxies strewn across cosmic time. Astronomers will use the survey’s data to explore invisible dark matter, detectable only via its gravitational effects on other objects, and the nature of dark energy — a pressure that seems to be speeding up the universe’s expansion.

“Cosmic acceleration is the biggest mystery in cosmology and maybe in all of physics,” Weinberg said. “Somehow, when we get to scales of billions of light years, gravity pushes rather than pulls. The Roman wide area survey will provide critical new clues to help us solve this mystery, because it allows us to measure the history of cosmic structure and the early expansion rate much more accurately than we can today.”

Weighing shadows

Anything that has mass warps space-time, the underlying fabric of the universe. Extremely massive things like clusters of galaxies warp space-time so much that they distort the appearance of background objects –– a phenomenon called gravitational lensing.

“It’s like looking through a cosmic funhouse mirror,” Hickox said. “It can smear or duplicate distant galaxies, or if the alignment is just right, it can magnify them like a natural telescope.”

Roman’s view will be large and sharp enough to study this lensing effect on a small scale to see how clumps of dark matter warp the appearance of distant galaxies. Astronomers will create a detailed map of the large-scale distribution of matter — both seen and unseen — throughout the universe and fill in more of the gaps in our understanding of dark matter. Studying how structures grow over time will also help astronomers explore dark energy’s strength at various cosmic stages.

“The data analysis standards required to measure weak gravitational lensing are such that the astronomy community as a whole will benefit from very high-quality data over the full survey area, which will undoubtedly lead to unexpected discoveries,” said Olivier Doré, a senior research scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, who leads a team focused on Roman imaging cosmology with the High-Latitude Wide-Area Survey. “This survey will accomplish much more than just revealing dark energy!”

While NASA’s Hubble and James Webb space telescopes both also study gravitational lensing, the breakthrough with Roman is its large field of view.

“Weak lensing distorts galaxy shapes too subtly to see in any single galaxy — it’s invisible until you do a statistical analysis,” Hickox said. “Roman will see more than a billion galaxies in this survey, and we estimate about 600 million of them will be detailed enough for Roman to study these effects. So Roman will trace the growth of structure in the universe in 3D from shortly after the big bang to today, mapping dark matter more precisely than we’ve ever done before.”

Sounding out dark energy

Roman’s wide-area survey will also gather spectra from around 20 million galaxies. Analyzing spectra helps show how the universe expanded during different cosmic eras because when an object recedes, all of the light waves we receive from it are stretched out and shifted toward redder wavelengths — a phenomenon called redshift.

By determining how quickly galaxies are receding from us, carried by the relentless expansion of space, astronomers can find out how far away they are –– the more a galaxy’s spectrum is redshifted, the farther away it is. Astronomers will use this phenomenon to make a 3D map of all the galaxies measured within the survey area out to about 11.5 billion light-years away.

That will reveal frozen echoes of ancient sound waves that once rippled through the primordial cosmic sea. For most of the universe’s first half-million years, the cosmos was a dense, almost uniform sea of plasma (charged particles).

Rare, tiny clumps attracted more matter toward themselves gravitationally. But it was too hot for the material to stick together, so it rebounded. This push and pull created waves of pressure — sound — that propagated through the plasma.

Over time, the universe cooled and the waves ceased, essentially freezing the ripples (called baryon acoustic oscillations) in place. Since the ripples were places where more matter was collected, slightly more galaxies formed along them than elsewhere. As the universe expanded over billions of years, so did these structures.

These rings act like a ruler for the universe. Today, they are about 500 million light-years wide. Roman will precisely measure their size across cosmic time, revealing how dark energy may have evolved.

Recent results from other telescopes hint that dark energy may be shifting in strength over cosmic time. “Roman will be able to make high precision tests that should tell us whether these hints are real deviations from our current standard model or not,” said Risa Wechsler, director of Stanford University’s KIPAC (Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology) in California and co-chair of the committee that shaped the survey’s design. “Roman’s imaging survey combined with its redshift survey give us new information about the evolution of the universe — both how it expands and how structures grow with time — that will help us understand what dark energy and gravity are doing at unprecedented precision.”

Altogether, Roman will help us understand the effects of dark energy 10 times more precisely than current measurements, helping discern between the leading theories that attempt to explain why the expansion of the universe is speeding up.

Because of the way Roman will survey the universe, it will reveal everything from small, rocky objects in our outer solar system and individual stars in nearby galaxies to galaxy mergers and black holes at the cosmic frontier over 13 billion years ago.

“Roman is exciting because it covers such a wide area with the image quality only available in space,” Wechsler said. “This enables a broad range of science, from things we can anticipate studying to discoveries that we haven’t thought of yet.”

The Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope is managed at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, with participation by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California; Caltech/IPAC in Pasadena, California; the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore; and a science team comprising scientists from various research institutions. The primary industrial partners are BAE Systems Inc. in Boulder, Colorado; L3Harris Technologies in Rochester, New York; and Teledyne Scientific & Imaging in Thousand Oaks, California.

By Ashley Balzer

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

Media contact:

Claire Andreoli

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

301-286-1940