Ancient bones reveal chilling victory rituals after Europe’s earliest wars

A study published in the journal Science Advances is reshaping how researchers understand early human violence. By closely examining

A study published in the journal Science Advances is reshaping how researchers understand early human violence. By closely examining the people who died in what may be one of Europe’s earliest known victory celebrations, scientists are challenging long-held assumptions about prehistoric warfare and its purpose.

The research, titled ‘Multi-isotope biographies and identities of victims of martial victory celebrations in Neolithic Europe’, was published in Science Advances and co-authored by Dr. Teresa Fernández-Crespo and Professor Rick Schulting. Using advanced multi-isotope analysis, the team reconstructed the life histories of individuals buried in mass graves in Alsace in northeastern France. These remains date back roughly 4300-4150 BCE.

Violence With Meaning, Not Chaos

The findings question the idea that prehistoric violence was random or driven only by survival. Instead, the evidence points to deliberate actions tied to social and symbolic goals.

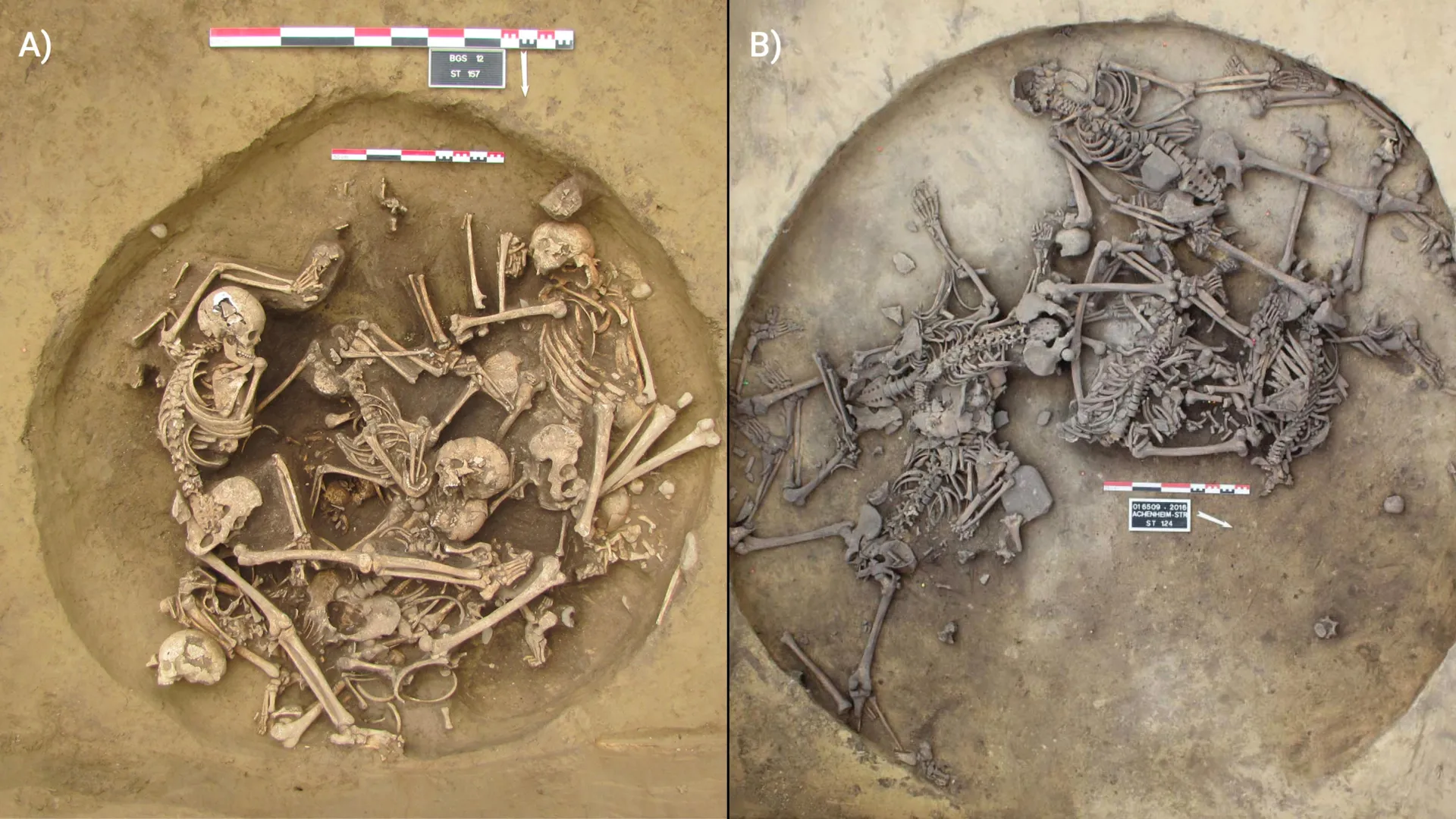

Archaeological excavations at the Achenheim and Bergheim sites revealed disturbing patterns. Researchers uncovered complete skeletons bearing signs of extreme and repeated violence, alongside pits filled with severed left upper limbs. This combination of excessive force and body part removal did not resemble known Neolithic massacres or executions. Rather than unplanned brutality, the researchers suggest these deaths were part of organized rituals carried out after conflict, meant to shame defeated enemies and strengthen group identity.

Chemical Clues From Ancient Bones

To better understand who these individuals were, scientists compared isotopic markers in the victims’ bones and teeth with those of people buried in standard graves. These chemical signatures reflect diet, movement, and physical stress over a lifetime.

The analysis showed clear differences. The victims had distinct dietary patterns and signs of greater mobility and physiological strain, indicating they were likely outsiders rather than members of the local community.

A Two-Tiered Ritual After Battle

The isotope data revealed another striking contrast. The severed limbs, thought to have been taken from warriors killed in combat, matched local isotopic values. In contrast, the individuals whose full skeletons showed signs of torture appeared to come from more distant regions.

This split supports the idea of a structured, two-level ritual. Local enemies killed in fighting were dismembered, with limbs brought back as trophies. Others, likely captives taken from afar, were subjected to violent executions. Researchers interpret this as a form of Neolithic political theatre designed to send a powerful message.

Professor Schulting said: “These findings speak to a deeply embedded social practice -one that used violence not just as warfare, but as spectacle, memory, and assertion of dominance.”

Rethinking Violence in Early Societies

By uncovering the social and cultural roles violence played during the Neolithic period, the study adds an important new perspective to human history. It suggests that war and ritual were closely linked, with acts of violence serving long-lasting symbolic purposes that shaped early societies.

The research was supported by a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions individual grant from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program, awarded to Dr. Fernández-Crespo. The project brought together researchers from multiple institutions, including the CNRS, Aix Marseille University, and Minist Culture, LAMPEA in Aix-en-Provence, France; the School of Archaeology at the University of Oxford, UK; the Department of Chemistry at Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Belgium; the Department of Archaeology and New Technologies at Arkikus, Spain; ANTEA-Archéologie, France; the University of Strasbourg, France; UMR 7044 Archimède, University of Strasbourg, France; and Inrap Grand Est, France.