This discovery could let bones benefit from exercise without moving

Researchers from the Department of Medicine at the School of Clinical Medicine, LKS Faculty of Medicine, University of Hong

Researchers from the Department of Medicine at the School of Clinical Medicine, LKS Faculty of Medicine, University of Hong Kong (HKUMed) have identified a biological process that explains how physical activity helps maintain strong bones. The discovery could lead to new treatments for osteoporosis and bone loss, particularly for people who are unable to exercise.

The team found that a specific protein acts as the body’s internal “exercise sensor,” allowing bones to respond to physical movement. This insight opens the possibility of developing medications that replicate the benefits of exercise, offering new hope for older adults, bedridden patients, and individuals with chronic illnesses who face a higher risk of fractures. The findings were published in the journal Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy.

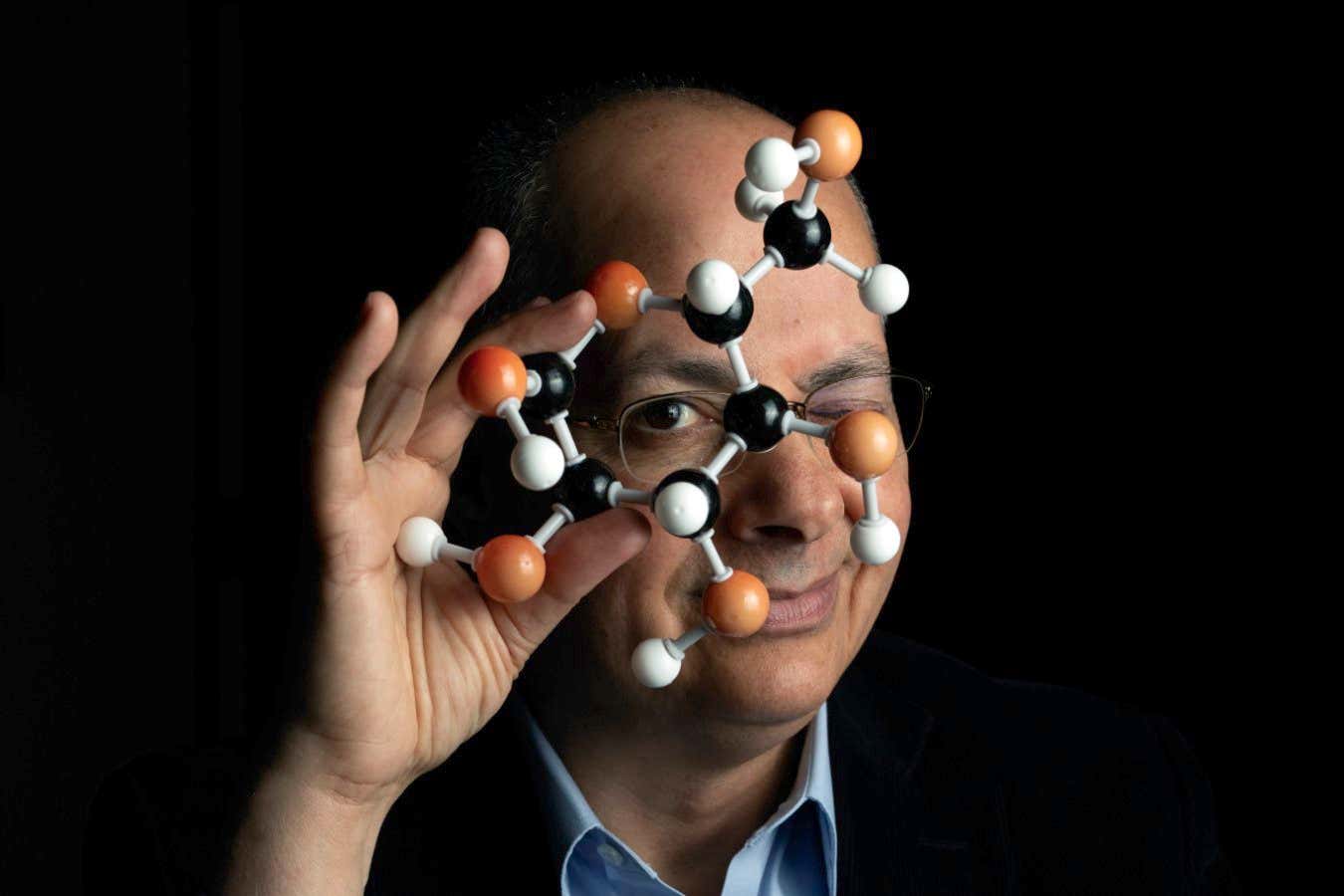

“Osteoporosis and age-related bone loss affect millions worldwide, often leaving elderly and bedridden patients vulnerable to fractures and loss of independence,” said Professor Xu Aimin, Director of the State Key Laboratory of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology and Chair Professor in the Department of Medicine, School of Clinical Medicine, HKUMed, who led the study. “Current treatments rely heavily on physical activity, which many patients simply cannot perform. We need to understand how our bones get stronger when we move or exercise before we can find a way to replicate the benefits of exercise at the molecular level. This study is a critical step towards that goal.”

Why Bone Loss Becomes More Severe With Age

Bone fractures caused by osteoporosis are a widespread global health problem. According to the World Health Organization, about one in three women and one in five men over the age of 50 will experience a fracture due to weakened bones. In Hong Kong, the impact is particularly significant as the population ages, with osteoporosis affecting 45% of women and 13% of men aged 65 and older. These fractures often result in long-term pain, reduced mobility, and loss of independence, while also placing major strain on healthcare systems.

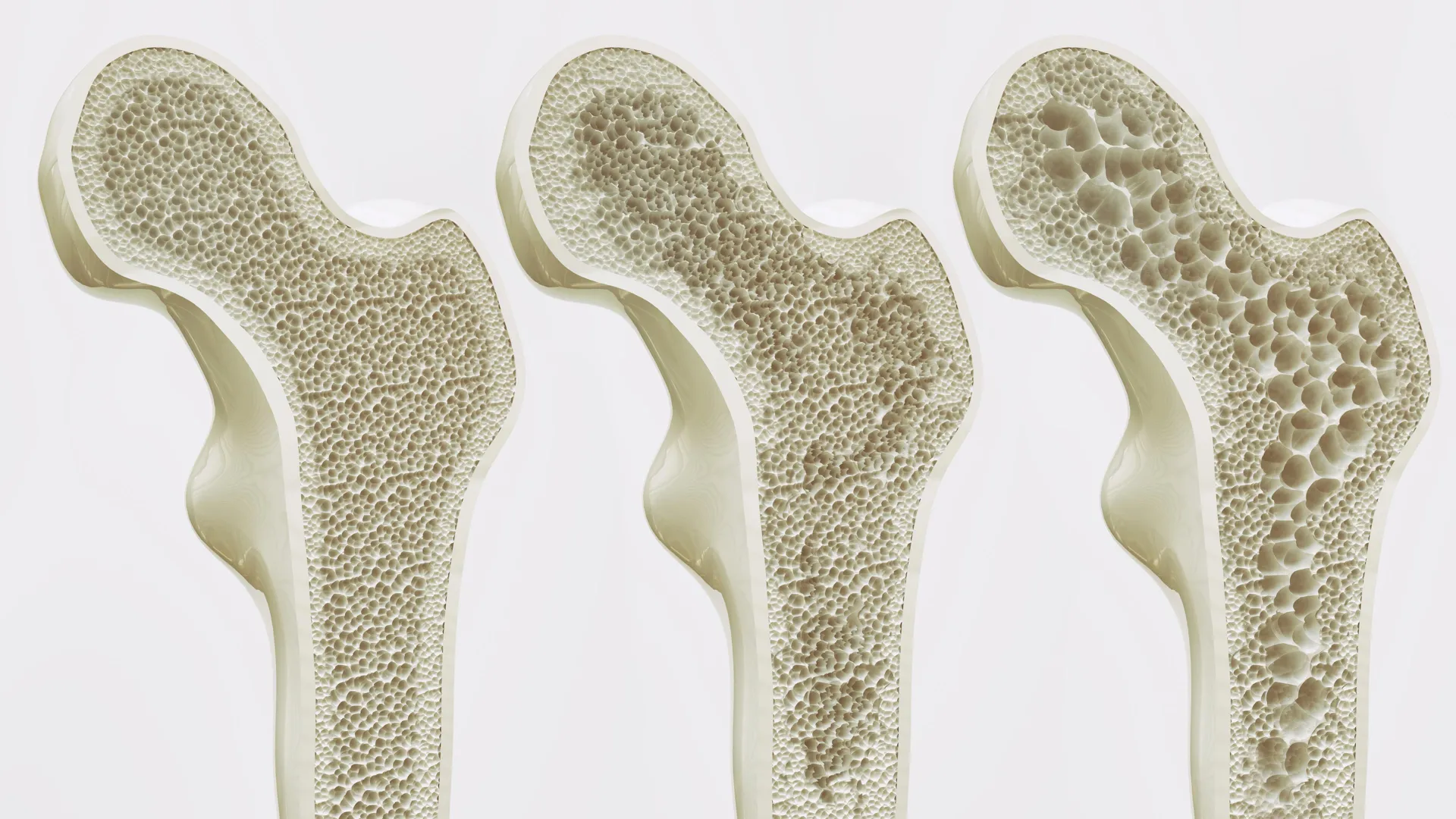

As people age, bones naturally lose density and become more porous. Inside the bone marrow are mesenchymal stem cells, which can develop into either bone tissue or fat cells. These cells respond strongly to physical forces such as movement and pressure. Over time, however, aging shifts this balance, causing more of these stem cells to turn into fat cells instead of bone.

When fat accumulates inside the bone marrow, it crowds out healthy bone tissue. This process weakens bones further and creates a cycle of deterioration that is difficult to reverse using current therapies.

Piezo1 Acts as the Bone’s Exercise Sensor

Through experiments using mouse models and human stem cells, the researchers identified a protein called Piezo1 located on the surface of mesenchymal stem cells in bone marrow. This protein functions as a mechanical sensor, detecting physical forces generated during movement and exercise.

When Piezo1 is activated through physical activity in mice, it limits fat buildup in the bone marrow and promotes new bone formation. When the protein is absent, the opposite occurs. Stem cells are more likely to become fat cells, accelerating bone loss. The lack of Piezo1 also triggers the release of inflammatory signals (Ccl2 and lipocalin-2), which further push stem cells toward fat production and interfere with bone growth. Blocking these signals was shown to help restore healthier bone conditions.

Mimicking Exercise for People Who Cannot Move

“We have essentially decoded how the body converts movement into stronger bones,” said Professor Xu Aimin. “We have identified the molecular exercise sensor, Piezo1, and the signalling pathways it controls. This gives us a clear target for intervention. By activating the Piezo1 pathway, we can mimic the benefits of exercise, effectively tricking the body into thinking it is exercising, even in the absence of movement.”

Dr Wang Baile, Research Assistant Professor in the same department and co-leader of the study, emphasized the importance of the findings for vulnerable populations. “This discovery is especially meaningful for older individuals and patients who cannot exercise due to frailty, injury or chronic illness. Our findings open the door to developing ‘exercise mimetics’ — drugs that chemically activate the Piezo1 pathway to help maintain bone mass and support independence.”

Professor Eric Honoré, Team Leader at the Institute of Molecular and Cellular Pharmacology, French National Centre for Scientific Research, and co-leader of the research, highlighted the broader potential impact. “This offers a promising strategy beyond traditional physical therapy. In the future, we could potentially provide the biological benefits of exercise through targeted treatments, thereby slowing bone loss in vulnerable groups such as the bedridden patients or those with limited mobility, and substantially reducing their risk of fractures.”

Moving Toward New Osteoporosis Treatments

The research team is now focused on translating these findings into clinical applications. Their goal is to develop new therapies that preserve bone strength and improve quality of life for aging individuals and those confined to bed.

The collaborative study was co-led by Professor Xu Aimin, Rosie T T Young Professor in Endocrinology and Metabolism, Chair Professor and Director, and Dr Wang Baile, Research Assistant Professor, State Key Laboratory of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, Department of Medicine, HKUMed. The project also involved Professor Eric Honoré from the Institute of Molecular and Cellular Pharmacology, French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS), Université Côte d’Azur (UniCA), and the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research (Inserm), who is also a Visiting Professor in the Department of Pharmacology and Pharmacy, HKUMed.

This research was supported by the Areas of Excellence Scheme and the General Research Fund of the Research Grants Council; the Health and Medical Research Fund under the Health Bureau, the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China; the National Key R&D Program of China; the National Natural Science Foundation of China; the Human Frontier Science Program; the French National Research Agency; Fondation de France; Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale; and the Macau Science and Technology Development Fund.