Ancient bacterium discovery rewrites the origins of syphilis

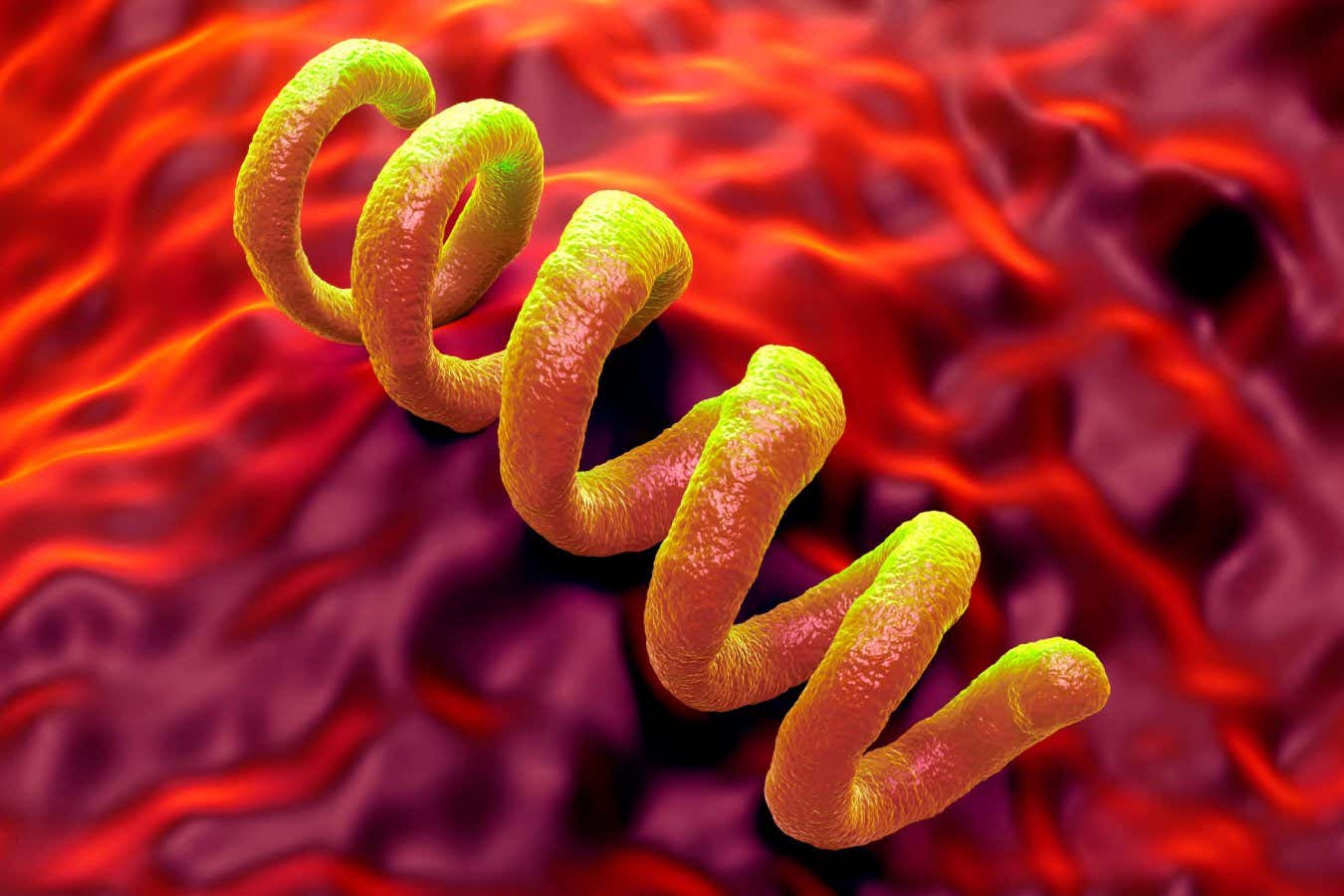

Treponema pallidum bacteria cause diseases including syphilis Science Photo Library / Alamy Traces of a bacterium related to syphilis

Treponema pallidum bacteria cause diseases including syphilis

Science Photo Library / Alamy

Traces of a bacterium related to syphilis have been found in a bone from a person who lived in the mountains of Colombia over 5000 years ago.

The discovery shows that this group of corkscrew-shaped bacteria was infecting humans thousands of years earlier than previously thought, before the rise of intensive agriculture, which many researchers consider a catalyst for the spread of pathogens.

Today, three subspecies of the bacterium Treponema pallidum cause the diseases syphilis, bejel and yaws. The deep history of these ailments is murky, and researchers have debated where diseases like syphilis arose and how they became widespread. Ancient bacterial DNA and markers of infection on skeletal remains lend us some clues, but these are rare and can be ambiguous.

So, when researchers studying the ancient DNA of 5500-year-old human remains in the Bogotá savannah detected the genome of Treponema pallidum in a human leg bone sample, it was a surprise.

“This finding was completely unexpected, because the individual studied had no skeletal evidence of a Treponema infection,” says Nasreen Broomandkhoshbacht at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

It is widely thought that many common diseases started to affect humanity after the dawn of intensive agriculture, when people began living in denser communities. But this individual lived in a very different context, where small hunter-gatherer groups travelled frequently and were in close contact with wildlife.

“Our results can tell us a lot about the long-term evolutionary history of [this bacterium] by revealing a long-standing association with human populations,” says Davide Bozzi at the University of Lausanne in Switzerland.

When Broomandkhoshbacht, Bozzi and their colleagues compared the ancient genome to those of other T. pallidum bacteria, they found it was part of a completely different lineage from any known modern relatives. This indicates that, millennia ago, ancient relatives of syphilis had already diversified in the Americas and were infecting humans, and the team’s analysis suggests they had many of the same genetic features that make today’s strains harmful.

The findings point to an early presence of these pathogens in the Americas, but it is also possible that they have been infecting humans for even longer across the world.

Rodrigo Barquera at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, notes that the ancient strain might belong to an elusive, “missing” pathogen: Treponema carateum, which causes a skin disease called pinta. The bacterium is only known from physical descriptions, not genetics.

Kerttu Majander at the University of Zurich, Switzerland, wonders what additional ancient genomes can tell us. “Were there perhaps many extinct lineages and perhaps different diseases caused by these pathogens in the past?” she says.

For Bozzi, understanding how pathogens evolve to cause diseases like syphilis and yaws is a crucial step in finding the genetic quirks that allow pathogens to infect new hosts and make their associated illnesses more dangerous.

Topics: