Earliest ever supernova sheds light on the first stars

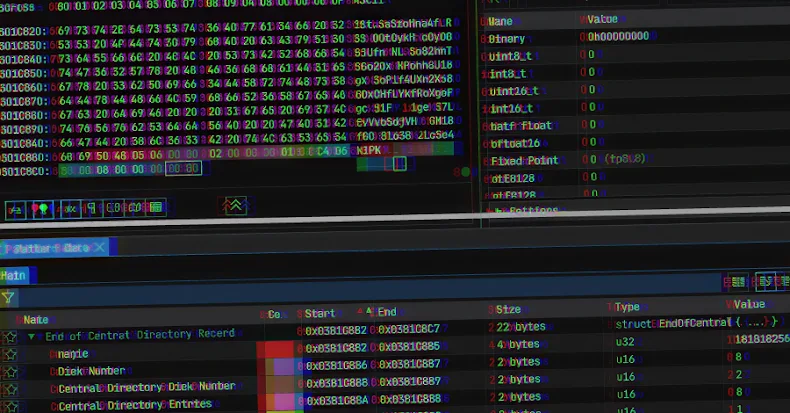

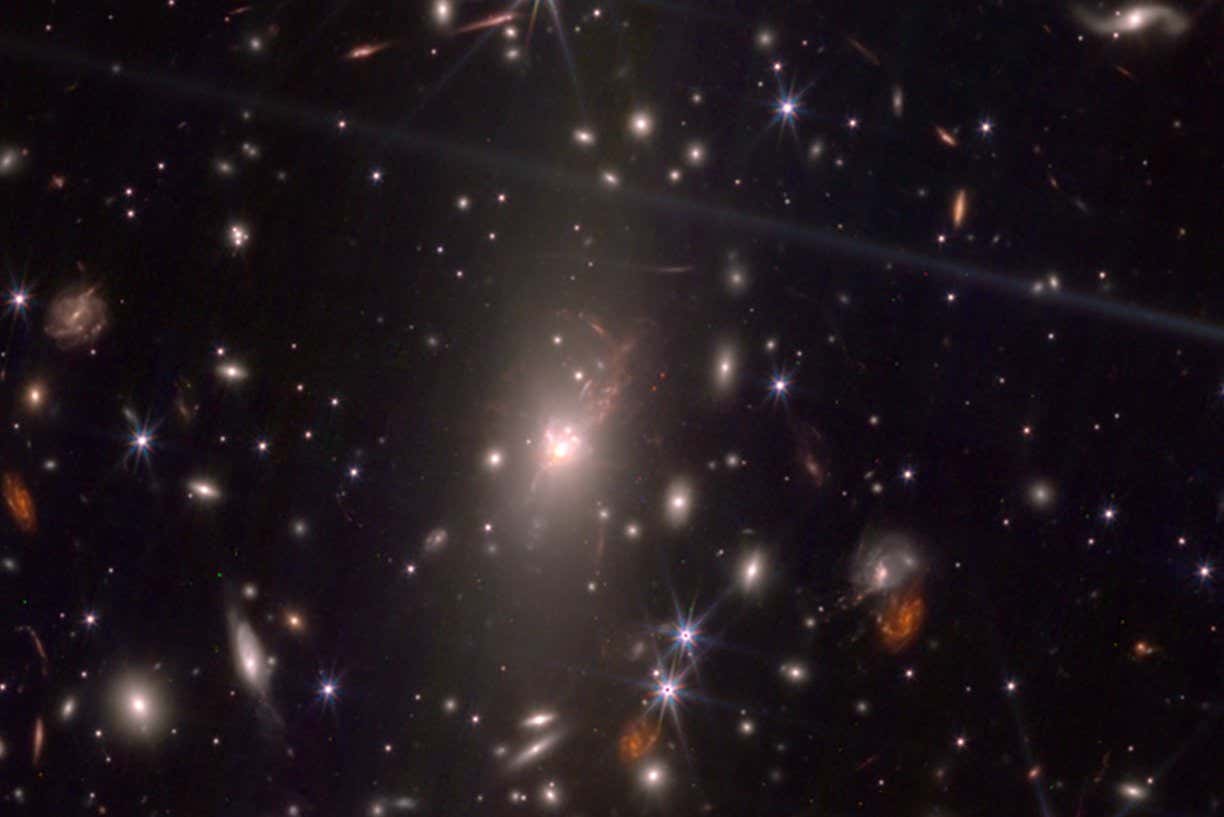

James Webb Space Telescope image of the galaxy cluster containing the SN Eos supernova Astronomers have caught a massive

James Webb Space Telescope image of the galaxy cluster containing the SN Eos supernova

Astronomers have caught a massive star exploding just moments after the universe emerged from the cosmic dark ages, shedding light on how the first stars were born and how they die.

When stars run out of fuel and explode, they produce a burst of powerful light called a supernova. Supernovae can look extremely bright in our local universe, but the light from a star exploding in the early universe can take billions of years to reach Earth, by which time it has dimmed and become too faint to see.

Because of this, astronomers can typically only see very distant supernovae in special cases, such as for type Ic supernovae, which are stellar cores that have lost their outer gas and produce an exceptionally bright burst of gamma rays. But the more typical type II supernovae, which are the most common stellar explosions we see in our galaxy and occur when a massive star runs out of fuel, are normally too faint to see.

Now, David Coulter at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, and his colleagues have spotted a type II supernova called SN Eos from when the universe was just a billion years old, using the James Webb Space Telescope.

The stellar explosion was fortunately placed behind a massive cluster of galaxies, whose powerful gravity magnified its light and made it tens of times brighter than it would normally appear, and so easier to study in detail.

The researchers analysed the spectrum of light coming from SN Eos, making it the earliest supernova that has been confirmed using spectroscopy. The results clearly show it is a type II supernova, which means it must have come from a massive star.

It also shows that the star that produced it had very low amounts of elements other than hydrogen or helium – less than 10 per cent of the amounts in our sun. This is how astronomers think the early universe looked, because there hadn’t been much time for multiple generations of stars to form and die and produce heavier elements.

“That tells us immediately about what kind of stellar population [the star] exploded in,” says Or Graur at the University of Portsmouth, UK. “High-mass stars explode very, very quickly after birth. In cosmological terms, a million years or so, that’s nothing. So they tell you about the ongoing star formation in that galaxy.”

When we see light at these distances, it’s typically from small galaxies, where you can infer average properties of what stars might be in those galaxies. But studying individual stars at these distances is typically not possible, says Matt Nicholl at Queen’s University Belfast, UK.

“We can see this individual star, with beautiful data, at a [distance] where we’ve never seen an isolated supernova, and the data are good enough to see that the stars are different from most of the stars in the local universe,” he says.

This would have been just a few hundred million years after a period in the universe’s history known as the epoch of reionisation, says Graur. That was when light from the first stars began to strip electrons from neutral hydrogen gas, which blocks most forms of radiation, and turned it into ionised hydrogen, which is transparent. Before this, the universe was opaque, so SN Eos is effectively as distant a supernova as we might hope to see.

“This is very, very close to that period of reionisation when the universe exited its short, dark period and photons could stream freely again and we could see things,” says Graur.

Topics: