Body fat supports your health in surprisingly complex ways

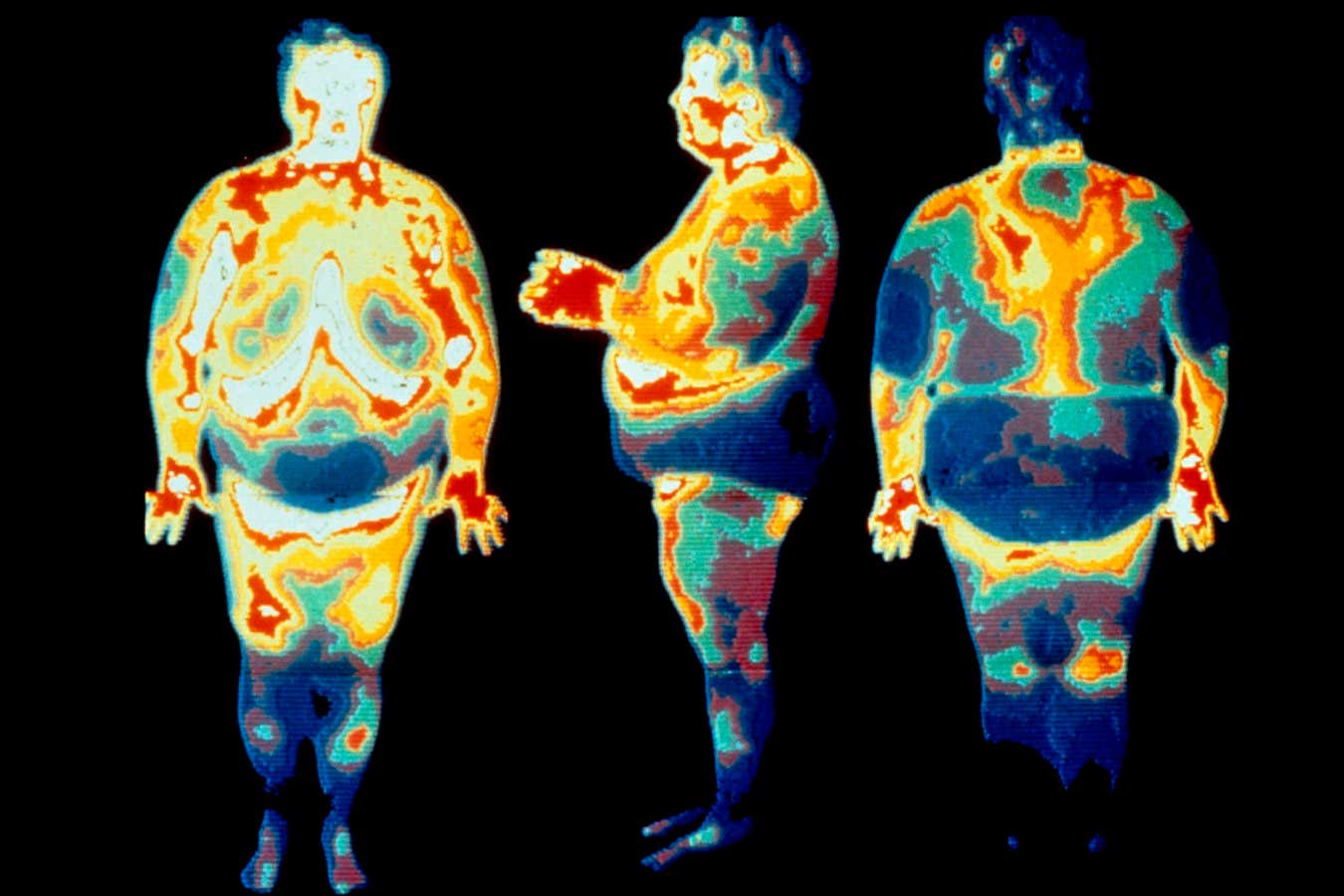

Too much body fat isn’t healthy, but some kinds can be beneficial DR RAY CLARK & MERVYN GOFF/SCIENCE PHOTO

Too much body fat isn’t healthy, but some kinds can be beneficial

DR RAY CLARK & MERVYN GOFF/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

If you thought body fat was just a passive storage depot for calories, think again. Research increasingly suggests that it plays an important role in our overall health, with two studies shedding new light on its complexity.

Fat exists in several forms. For instance, there’s white fat, which stores energy and releases hormones that influence metabolism; brown fat, which generates heat; and beige fat, which sits somewhere in between, switching on heat production under certain conditions. Even within these categories, location matters: fat under the skin is generally less harmful, while fat deep inside the abdomen – known as visceral fat – is strongly linked to inflammation, type 2 diabetes and heart disease.

The latest research adds further flesh to this picture, suggesting that fat, or adipose tissue, actively helps to regulate blood pressure and coordinate immune responses at key locations.

In one of the studies, Jutta Jalkanen at Karolinska University Hospital in Stockholm, Sweden, and her colleagues mapped the cellular architecture of visceral fat from multiple locations within the abdomen. They found that epiploic fat, which wraps around the large intestine, is unusually rich in immune cells, as well as specialised fat cells that produce inflammatory proteins associated with immune activation. Further experiments showed that microbial products originating in the gut trigger these fat cells to activate nearby immune cells.

“Our work shows that fat depots appear to be specialised according to their anatomical location, and those that sit right next to the intestine seem particularly adapted for immune interaction,” says Jalkanen.

Although the study involved people with obesity, Jalkanen suspects that epiploic fat serves similar core functions in people of all body weights, since everyone has some fat surrounding their intestine.

“The intestine is constantly exposed to nutrients, microbial products and substances coming from our environment,” says Jalkanen. “Having fat tissue nearby that can sense, respond to, and help coordinate immune reactions could provide an additional layer of protection.”

In obesity, however, this system may become chronically overactivated. Eating too much, or too much of certain foods, and having particular bacterial compositions within the gut microbiome could potentially drive persistent immune signalling in intestinal fat, contributing to the low-grade inflammation linked to a range of metabolic conditions, such as type 2 diabetes and obesity.

The second study reveals another unexpected role for fat: controlling blood pressure. Mascha Koenen at The Rockefeller University in New York and her colleagues set out to understand why obesity, characterised by excess white fat, is linked to high blood pressure, while brown and beige fat appear to be protective.

They focused on perivascular adipose tissue, a fatty layer rich in beige fat calls that surrounds blood vessels. In mice genetically engineered to lose their beige fat, blood vessels became stiffer and overreacted to everyday hormonal signals that constrict arteries, leading to elevated blood pressure.

The team traced this effect to an enzyme called QSOX1, released by dysfunctional fat cells. Blocking it prevented blood vessel damage and normalised blood pressure in mice, regardless of their body weight. “What this nicely shows is that the communication between different organ systems is critical to understand complex diseases such as hypertension and blood pressure regulation,” says Koenen.

“This study reveals an under-appreciated role for brown or beige fat,” says Kristy Townsend at The Ohio State University in Columbus. While deposits of perivascular adipose tissue are proportionately smaller in people than they are in mice, they are still probably physiologically relevant in us, she says. “[The study] emphasises a need for nuanced understanding of adipose impacts on health, independent of fat mass or body mass index (BMI) overall.”

The findings point to future therapies that focus less on simply reducing fat and more on preserving or restoring its beneficial functions by targeting specific fat depots, modulating immune-fat communication or maintaining healthy beige fat activity. However, any clinical applications would require further research.

Together, the studies highlight fat as an active, functionally diverse tissue involved in multiple aspects of human physiology. “When I started working in this field in the late 1990s, the prevailing view was that fat was just a simple bag of cells that stored excess nutrients,” says Paul Cohen, also at The Rockefeller University, who was involved with the second study. “These studies illustrate a growing shift in the field: recognising fat not as a single cell type, but as a complex tissue with many different types of cells with different roles and diverse processes, extending well beyond just nutrient storage and mobilisation.”

Topics: