NASA’s Webb telescope just discovered one of the weirdest planets ever

Scientists using NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope have identified a previously unknown kind of exoplanet, one whose atmosphere defies

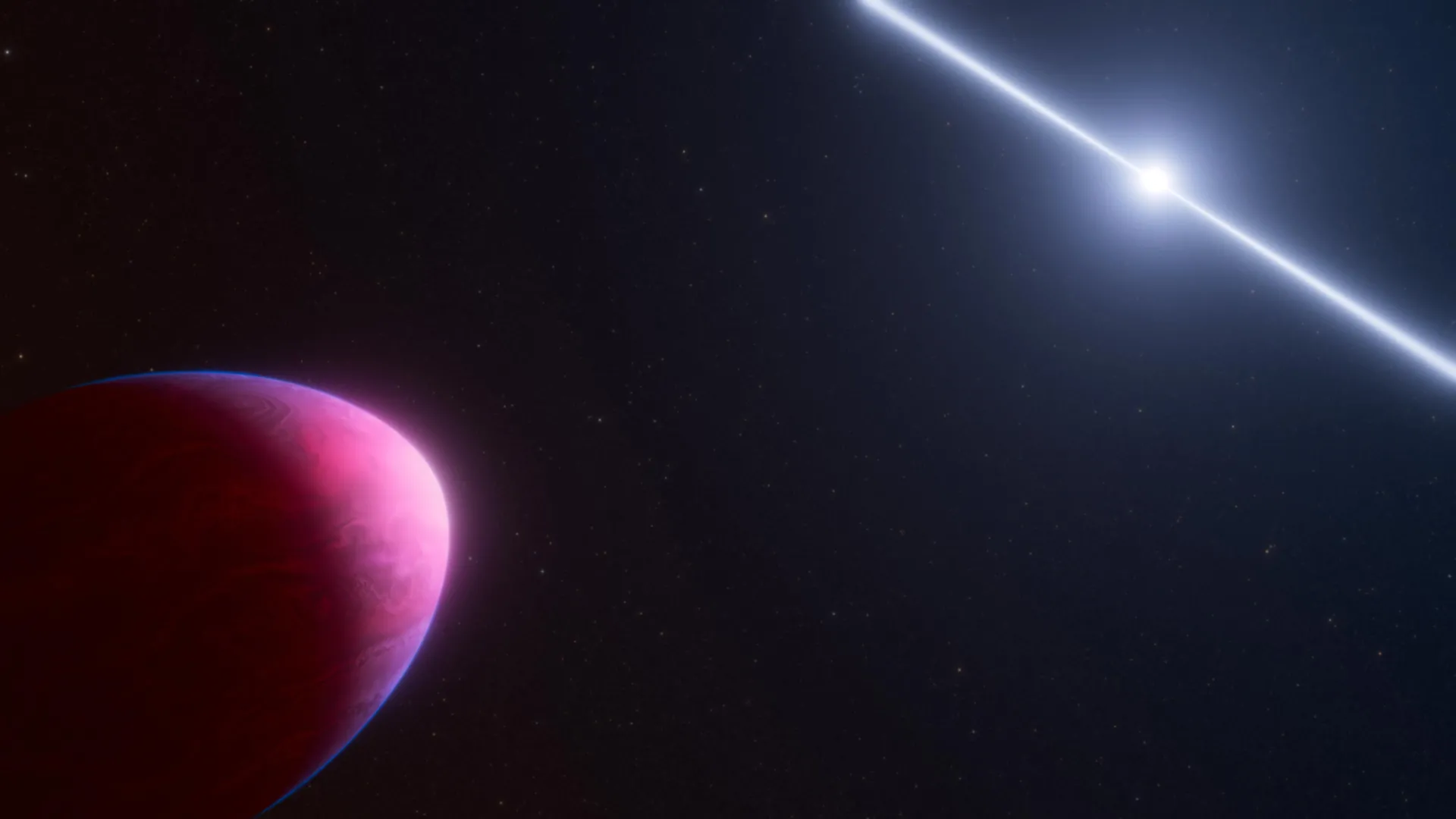

Scientists using NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope have identified a previously unknown kind of exoplanet, one whose atmosphere defies current ideas about how planets are supposed to form.

The newly observed world has a stretched, lemon-like shape and may even contain diamonds deep inside. Its strange characteristics make it difficult to classify, sitting somewhere between what astronomers typically consider a planet and a star.

A Carbon World Unlike Any Other

The object, officially named PSR J2322-2650b, has an atmosphere dominated by helium and carbon rather than the familiar gases seen on most known exoplanets. With a mass comparable to Jupiter, the planet is shrouded in dark soot-like clouds. Under the intense pressures inside the planet, scientists believe carbon from these clouds could be compressed into diamonds. The planet circles a rapidly spinning neutron star.

Despite detailed observations, how this planet formed remains unknown.

“The planet orbits a star that’s completely bizarre — the mass of the Sun, but the size of a city,” said University of Chicago astrophysicist Michael Zhang, the study’s principal investigator. The research has been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. “This is a new type of planet atmosphere that nobody has ever seen before.”

“This was an absolute surprise,” said Peter Gao of the Carnegie Earth and Planets Laboratory in Washington, D.C. “I remember after we got the data down, our collective reaction was ‘What the heck is this?'”

A Planet Orbiting a Pulsar

PSR J2322-2650b orbits a neutron star, also known as a pulsar, that spins at extraordinary speed.

Pulsars emit powerful beams of electromagnetic radiation from their magnetic poles at intervals measured in milliseconds. Most of that radiation comes in the form of gamma rays and other high-energy particles that are invisible to Webb’s infrared instruments.

Because the star itself does not overwhelm Webb’s detectors, researchers can observe the planet throughout its entire orbit. This is rarely possible, since most stars shine far brighter than the planets around them.

“This system is unique because we are able to view the planet illuminated by its host star, but not see the host star at all,” said Maya Beleznay, a Stanford University graduate student who helped model the planet’s shape and orbit. “So we get a really pristine spectrum. And we can better study this system in more detail than normal exoplanets.”

A Startling Atmospheric Discovery

When scientists analyzed the planet’s atmospheric signature, they found something entirely unexpected.

“Instead of finding the normal molecules we expect to see on an exoplanet — like water, methane and carbon dioxide — we saw molecular carbon, specifically C3 and C2,” Zhang said.

The extreme pressure inside the planet could cause that carbon to crystallize, potentially forming diamonds deep below the surface.

Still, the most puzzling issue remains unanswered.

“It’s very hard to imagine how you get this extremely carbon-enriched composition,” Zhang said. “It seems to rule out every known formation mechanism.”

A Planet in a Deadly Embrace

PSR J2322-2650b orbits extraordinarily close to its star, just 1 million miles away. By comparison, Earth sits about 100 million miles from the Sun.

Because of this proximity, the planet completes a full orbit in just 7.8 hours (the time it takes to go around its star).

By modeling subtle changes in the planet’s brightness as it moves, researchers determined that intense gravitational forces from the much heavier pulsar are stretching the planet into its lemon-like shape.

The system may belong to a rare category known as a black widow. In these systems, a fast-spinning pulsar is paired with a smaller, low-mass companion. In earlier stages, material from the companion flowed onto the pulsar, increasing its spin and fueling a powerful wind. That wind, along with intense radiation, gradually strips material away from the smaller object.

Like the spider it is named after, the pulsar slowly consumes its partner.

In this case, however, the companion is classified as an exoplanet by the International Astronomical Union, not a star.

“Did this thing form like a normal planet? No, because the composition is entirely different,” Zhang said. “Did it form by stripping the outside of a star, like ‘normal’ black widow systems are formed? Probably not, because nuclear physics does not make pure carbon.”

A Mystery Scientists Are Eager to Solve

Roger Romani of Stanford University and the Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology is one of the world’s leading experts on black widow systems. He has proposed a possible explanation for the planet’s strange atmosphere.

“As the companion cools down, the mixture of carbon and oxygen in the interior starts to crystallize,” Romani said. “Pure carbon crystals float to the top and get mixed into the helium, and that’s what we see. But then something has to happen to keep the oxygen and nitrogen away. And that’s where there’s controversy.”

“But it’s nice to not know everything,” Romani added. “I’m looking forward to learning more about the weirdness of this atmosphere. It’s great to have a puzzle to go after.”

Why Webb Made the Difference

This discovery was only possible because of the James Webb Space Telescope’s infrared sensitivity and unique observing conditions. Positioned about a million miles from Earth, Webb uses a massive sunshield to keep its instruments extremely cold, which is essential for detecting faint infrared signals.

“On the Earth, lots of things are hot, and that heat really interferes with the observations because it’s another source of photons that you have to deal with,” Zhang said. “It’s absolutely not feasible from the ground.”

Additional University of Chicago contributors included Prof. Jacob Bean, graduate student Brandon Park Coy, and Rafael Luque, who was a postdoctoral researcher at UChicago and is now with the Instituto de Astrofísica de Andalucía in Spain.

Funding for the research came from NASA and the Heising-Simons Foundation.