New images reveal what really happens when stars explode

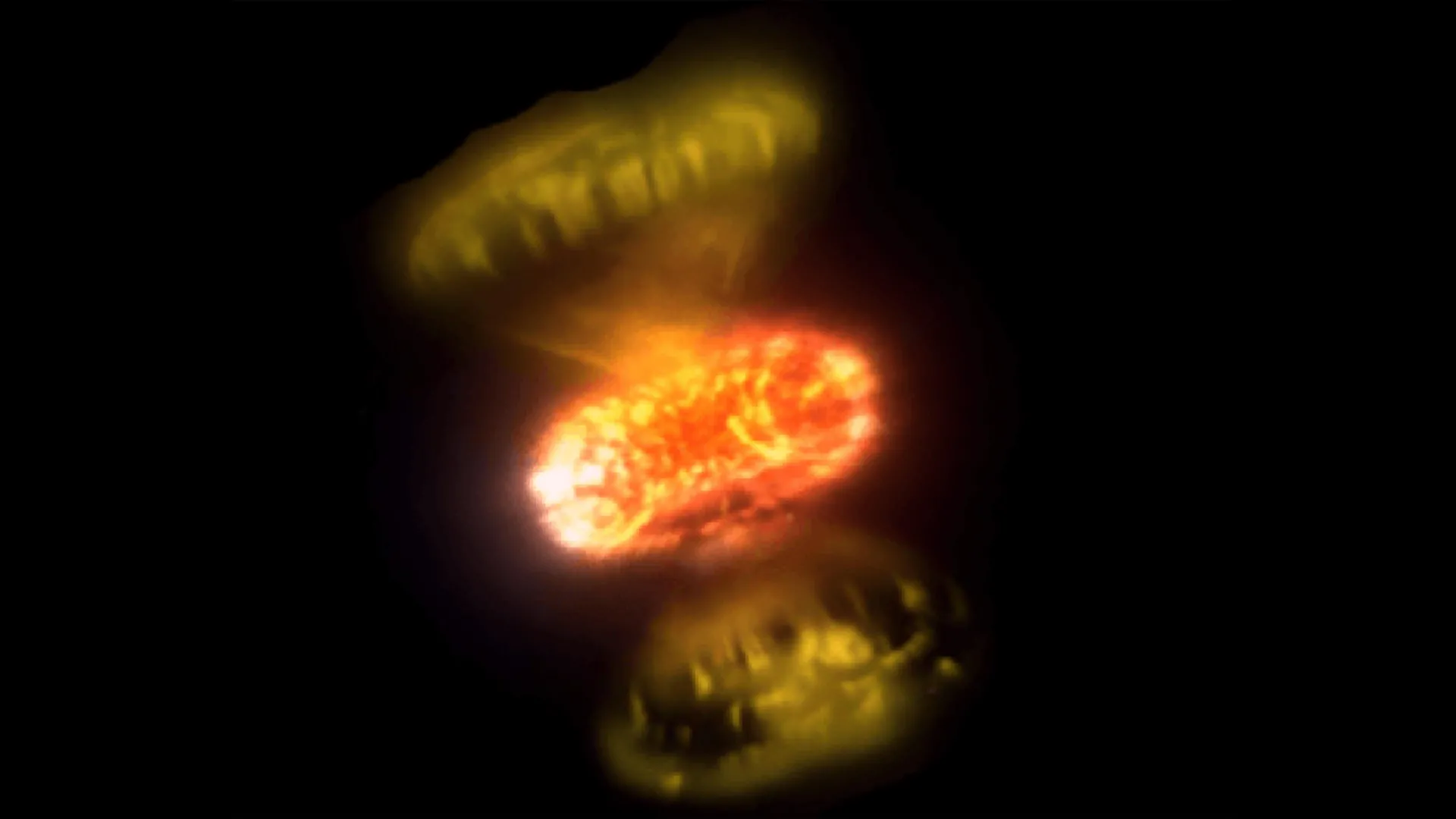

Astronomers have obtained remarkably detailed images of two stellar explosions — called novae — just days after they began.

Astronomers have obtained remarkably detailed images of two stellar explosions — called novae — just days after they began. The new observations offer clear proof that these outbursts are not as simple as once believed. Instead of a single blast, the explosions can send out more than one stream of material and may even delay some of the ejection in dramatic ways.

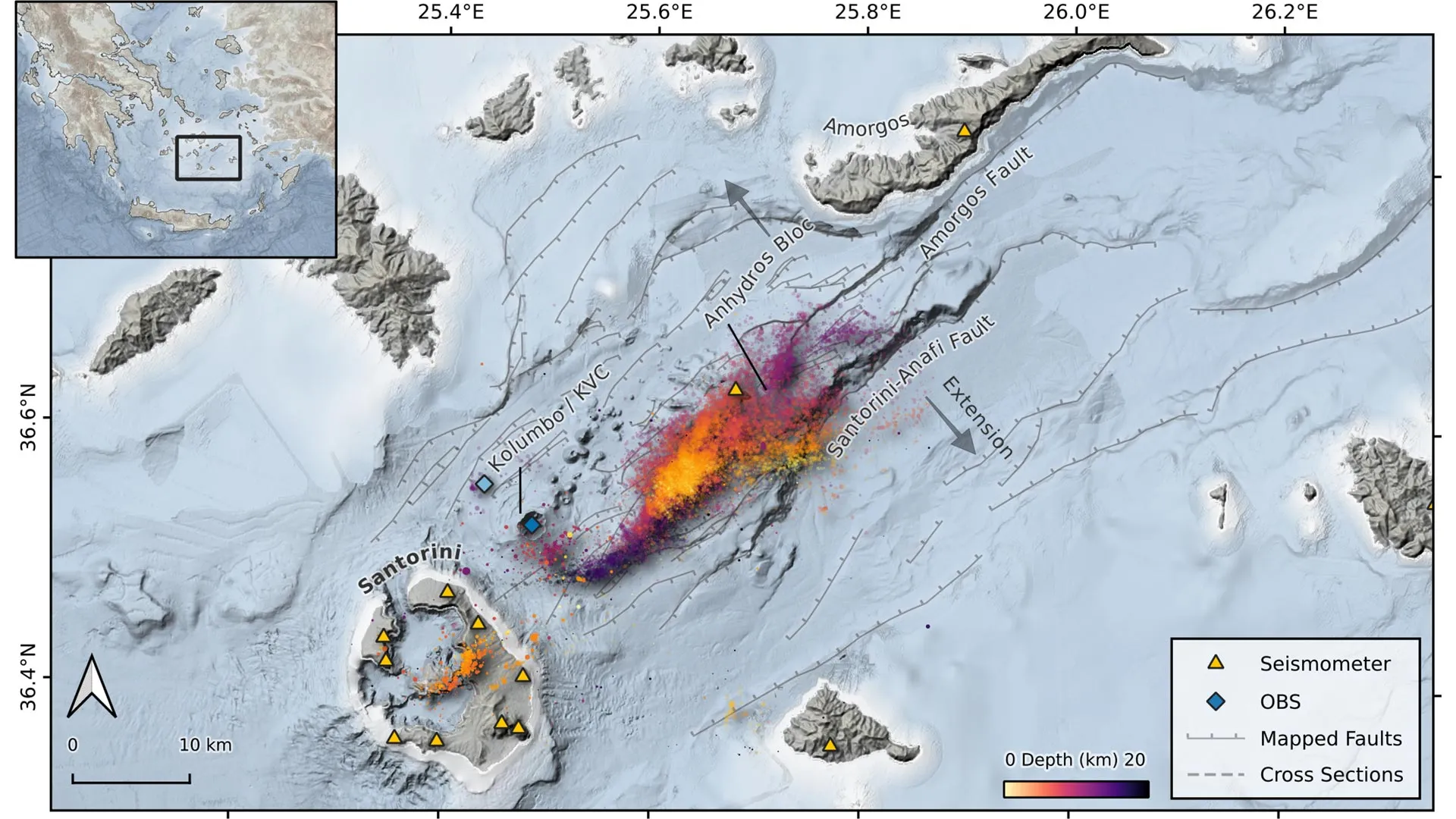

The international research team reported the work in Nature Astronomy. They used interferometry at the Center for High Angular Resolution Astronomy (CHARA Array) in California, a method that combines light from multiple telescopes to create extremely sharp views. That added resolution made it possible to directly image these fast-changing events as they evolved.

“The images give us a close-up view of how material is ejected away from the star during the explosion,” said Georgia State’s Gail Schaefer, director of the CHARA Array. “Catching these transient events requires flexibility to adapt our night-time schedule as new targets of opportunity are discovered.”

What a Nova Is and Why Shock Waves Matter

A nova happens in a close binary system when a white dwarf, the dense leftover core of a star, pulls gas from a nearby companion. As the stolen material builds up, it can ignite in a runaway nuclear reaction, triggering a sudden brightening in the sky. Until recently, astronomers mostly had to piece together the earliest stages indirectly because the expanding debris looked like a single pinpoint of light.

Seeing exactly how the ejecta blast outward and interact is key to explaining how shock waves form in novae. Those shocks were first linked to novae by NASA’s Fermi Large Area Telescope (LAT). During its first 15 years, Fermi-LAT detected GeV emission from more than 20 novae, showing that these eruptions can produce gamma rays in our galaxy and pointing to their promise as multi-messenger sources.

Two 2021 Novae With Very Different Behavior

The team focused on two novae that erupted in 2021 and found that they behaved in strikingly different ways. Nova V1674 Herculis was one of the fastest ever recorded, rising and fading within days. The images revealed two separate gas flows moving in perpendicular directions — a sign that the event involved multiple ejections interacting with each other. The timing was especially telling: the new outflows appeared in the images while NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope was also detecting high-energy gamma rays, directly connecting the shock-powered radiation to those colliding streams.

Nova V1405 Cassiopeiae unfolded much more slowly. It unexpectedly held onto its outer layers for more than 50 days before releasing them, offering the clearest evidence yet for a delayed expulsion in a nova. When that material finally broke free, it set off fresh shocks, and NASA’s Fermi again observed gamma rays tied to the renewed violence.

“These observations allow us to watch a stellar explosion in real time, something that is very complicated and has long been thought to be extremely challenging,” said Elias Aydi, lead author of the study and a professor of physics and astronomy at Texas Tech University. “Instead of seeing just a simple flash of light, we’re now uncovering the true complexity of how these explosions unfold. It’s like going from a grainy black-and-white photo to high-definition video.”

Interferometry Reveals Structure and Spectra Confirm the Details

The ability to see such fine structure comes from interferometry, the same type of technique used to help image the black hole at the center of our galaxy. The team also compared the images with spectra from major facilities such as Gemini. Those spectra tracked changing signatures in the ejected gas, and new spectral features matched up with structures seen in the interferometric images, providing a direct one-to-one confirmation of how the flows were forming and colliding.

“This is an extraordinary leap forward,” said John Monnier, a professor of astronomy at the University of Michigan, a co-author of the study and an expert in interferometric imaging. “The fact that we can now watch stars explode and immediately see the structure of the material being blasted into space is remarkable. It opens a new window into some of the most dramatic events in the universe.”

What This Changes About Stellar Explosions and Gamma Rays

The findings show that novae can be far more complicated than a single sudden outburst. They also help explain why these events generate strong shocks that produce high-energy light, including gamma rays. NASA’s Fermi telescope has been central to uncovering that connection, turning novae into real-world laboratories for studying shock physics and particle acceleration.

“Novae are more than fireworks in our galaxy — they are laboratories for extreme physics,” said Professor Laura Chomiuk, a co-author from Michigan State University and an expert on stellar explosions. “By seeing how and when the material is ejected, we can finally connect the dots between the nuclear reactions on the star’s surface, the geometry of the ejected material and the high-energy radiation we detect from space.”

Overall, the results challenge the long-standing idea that nova eruptions are single, impulsive events. The observations instead point to multiple ways a nova can unfold, including several outflows and delayed release of the star’s outer envelope, reshaping how scientists understand these explosive episodes.

“This is just the beginning,” Aydi said. “With more observations like these, we can finally start answering big questions about how stars live, die and affect their surroundings. Novae, once seen as simple explosions, are turning out to be much richer and more fascinating than we imagined.”

The images of the two novae were collected through the CHARA Array open-access program, supported by the National Science Foundation under Grants No. AST-2034336 and AST-2407956. Georgia State’s College of Arts & Sciences, Office of the Provost and Office of the Vice President for Research and Economic Development also provide institutional support for the CHARA Array.