Could 2026 be the year we start using quantum computers for chemistry?

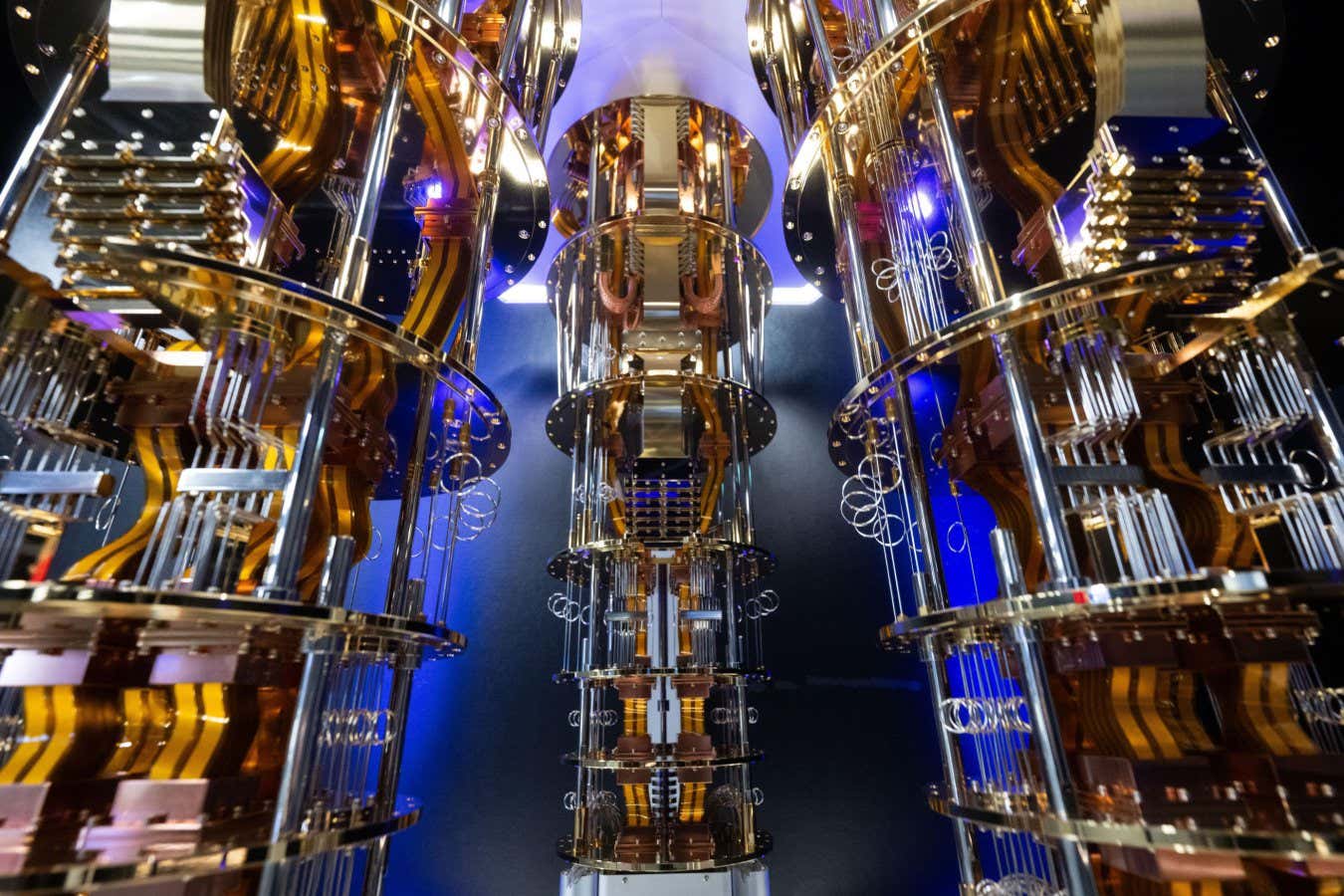

Quantum computers are well-matched to solve chemistry problems Marijan Murat/dpa/Alamy Whether quantum computers can actually solve practical problems is

Quantum computers are well-matched to solve chemistry problems

Marijan Murat/dpa/Alamy

Whether quantum computers can actually solve practical problems is one of the biggest unanswered questions of this growing industry – and one that might be answered by researchers in industrial and medical chemistry in 2026.

Calculating the structure, reactivity and other chemical properties of a molecule is an intrinsically quantum problem because it involves its electrons, which are quantum particles. But the more complex a molecule is, the harder these calculations become, in some cases posing a real challenge even for traditional supercomputers.

On the other hand, because quantum computers are also intrinsically quantum, they should have an advantage when it comes to tackling these chemical calculations. And as quantum computers have gotten larger and more easily combined with traditional computers, we are increasingly seeing them turned to this use.

For example, in 2025, researchers at IBM and the Japanese scientific institute RIKEN used a quantum computer and a supercomputer to model several molecules. Researchers at Google developed and tested a quantum computing algorithm to help tease out the structure of molecules. RIKEN’s researchers also teamed up with the quantum computing firm Quantinuum to devise a workflow for computing molecules’ energies in such a way that the quantum computer caught its own errors. Finally, quantum software start-up Qunova Computing already provides an algorithm that partly uses a quantum computer to calculate these energies, which it claims is about 10 times more efficient than more traditional methods.

We should expect to see much more of this in 2026 as larger quantum computers become available. “Upcoming bigger machines will allow us to develop more powerful versions of this [existing] workflow, and ultimately, we’ll be able to address general quantum chemistry problems,” says David Muñoz Ramo at Quantinuum. So far, his team has tackled only a hydrogen molecule, but he says that more complex structures like catalysts, which speed up industrially relevant reactions, could be on the horizon.

Other research teams are gearing up to do similar work. For example, in December, Microsoft announced a collaboration with the quantum software start-up Algorithmiq with the explicit aim of developing more quantum chemistry algorithms more quickly. In fact, a survey of the quantum computing industry conducted by Hyperion Research found that chemistry is the leading area in which makers and buyers of quantum computers alike expect to see progress and success in the coming year. In the past two annual surveys, quantum chemistry was the second- and fourth-most promising use case for quantum computing, respectively, so the trend has seen steadily increasing interest and investment.

Ultimately, however, quantum chemistry computations won’t really take off until quantum computers become error-proof or fault-tolerant – something that is also holding up other applications of these exotic devices. “The ability of a quantum computer to solve problems faster than a classical computer depends on fault-tolerant algorithm,” wrote Philipp Schleich and Alán Aspuru-Guzik at the University of Toronto in a recent commentary on quantum computing and chemistry for the journal Science. Luckily, reaching fault-tolerance is the one goal that every quantum computer manufacturer around the globe can agree on.

Topics: