The brain has a hidden language and scientists just found it

Scientists have developed a protein that can record the chemical messages brain cells receive, rather than focusing only on

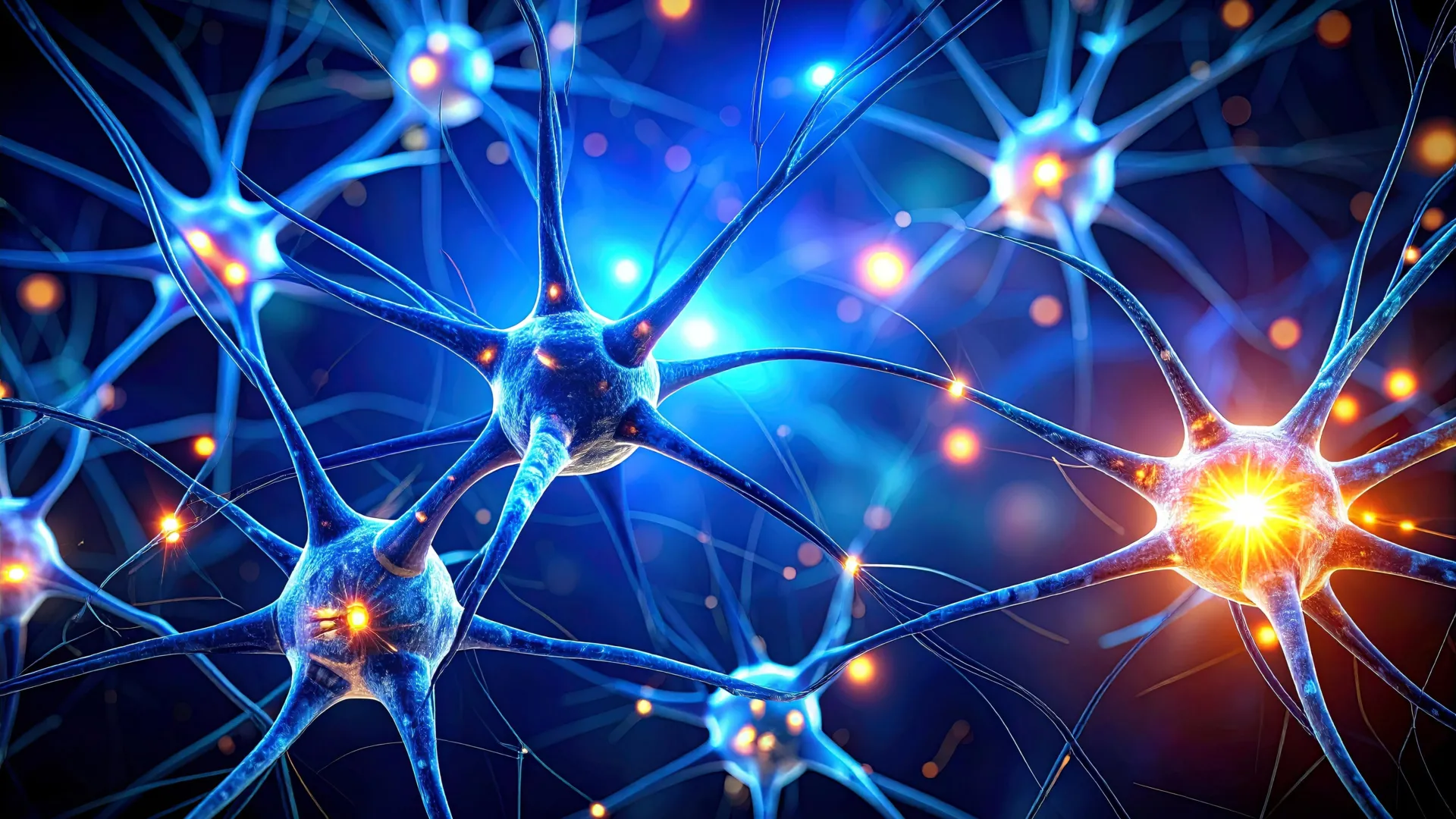

Scientists have developed a protein that can record the chemical messages brain cells receive, rather than focusing only on the signals they send out. These incoming signals are created when neurons release glutamate, a neurotransmitter that plays a vital role in brain communication. Although glutamate is essential for processes like learning and memory, its activity has been extremely difficult to measure because the signals are faint and happen very quickly.

This new tool makes it possible to detect those subtle chemical messages as they arrive, giving researchers access to a part of brain communication that has long been hidden.

Why this discovery matters

Being able to observe incoming signals allows scientists to study how neurons process information. Each brain cell receives thousands of inputs, and how it combines those signals determines whether it produces an output. This process is thought to underlie decisions, thoughts, and memories, and studying it directly could help explain how the brain performs complex computations.

The advance also opens new paths for disease research. Problems with glutamate signaling have been linked to conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, schizophrenia, autism, epilepsy, and others. By measuring these signals more precisely, researchers may be able to identify the biological roots of these disorders.

Drug development could also benefit. Pharmaceutical companies can use these sensors to see how experimental treatments affect real synaptic activity, which may help speed up the search for more effective therapies.

Introducing a powerful glutamate sensor

The protein was engineered by researchers at the Allen Institute and HHMI’s Janelia Research Campus. Known as iGluSnFR4 (pronounced ‘glue sniffer’), it acts as a molecular “glutamate indicator.” Its sensitivity allows it to detect even the weakest incoming signals exchanged between neurons.

By revealing when and where glutamate is released, iGluSnFR4 provides a new way to interpret the complex patterns of brain activity that support learning, memory, and emotion. It gives scientists the ability to watch neurons communicate inside the brain in real time. The findings were recently published in Nature Methods and could significantly change how neural activity is measured and analyzed in neuroscience research.

How brain cells communicate

To understand the impact of this advance, it helps to look at how neurons interact. The brain contains billions of neurons that communicate by sending electrical signals along branch-like structures called axons. When an electrical signal reaches the end of an axon, it cannot cross the small gap to the next neuron, which is known as a synapse.

Instead, the signal triggers the release of neurotransmitters into the synapse. Glutamate is the most common of these chemical messengers and plays a key role in memory, learning, and emotion. When glutamate reaches the next neuron, it can cause that cell to fire, continuing the chain of communication.

From fragments to the full conversation

This process can be compared to falling dominos, but it is far more complex. Each neuron receives input from thousands of others, and only certain combinations and patterns of activity will trigger the receiving neuron to fire. With this new protein sensor, scientists can now identify which patterns of incoming activity lead to that response.

Until now, observing these incoming signals in living brain tissue was nearly impossible. Previous technologies were too slow or lacked the sensitivity needed to measure activity at individual synapses. As a result, researchers could only see pieces of the communication process rather than the full exchange. This new approach allows them to capture the entire conversation.

Making sense of neural connections

“It’s like reading a book with all the words scrambled and not understanding the order of the words or how they’re arranged,” said Kaspar Podgorski, Ph.D., a lead author of the study and senior scientist at the Allen Institute. “I feel like what we’re doing here is adding the connections between those neurons and by doing that, we now understand the order of the words on the pages, and what they mean.”

Before protein sensors like iGluSnFR4 were available, researchers could only measure outgoing signals from neurons. This left a major gap in understanding, since the incoming signals were too fast and too faint to detect.

“Neuroscientists have pretty good ways of measuring structural connections between neurons, and in separate experiments, we can measure what some of the neurons in the brain are saying, but we haven’t been good at combining these two kinds of information. It’s hard to measure what neurons are saying to which other neurons,” Podgorski said. “What we have invented here is a way of measuring information that comes into neurons from different sources, and that’s been a critical part missing from neuroscience research.”

Collaboration behind the breakthrough

“The success of iGluSnFR4 stems from our close collaboration started at HHMI’s Janelia Research Campus between the GENIE Project team and Kaspar’s lab. That research has extended to the phenomenal in vivo characterization work done by the Allen Institute’s Neural Dynamics group,” said Jeremy Hasseman, Ph.D., a scientist with HHMI’s Janelia Research Campus. “This was a great example of collaboration across labs and institutes to enable new discoveries in neuroscience.”

A new window into brain function

This discovery overcomes a major limitation in modern neuroscience by making it possible to directly observe how neurons receive information. With iGluSnFR4 now available to researchers through Addgene, scientists have a powerful new tool to explore brain function in greater detail. As this technology spreads, it may help reveal answers to some of the brain’s most enduring questions.