MIT scientists find a way to rejuvenate the immune system as we age

As people get older, the immune system often becomes less effective. Populations of T cells shrink, and the remaining

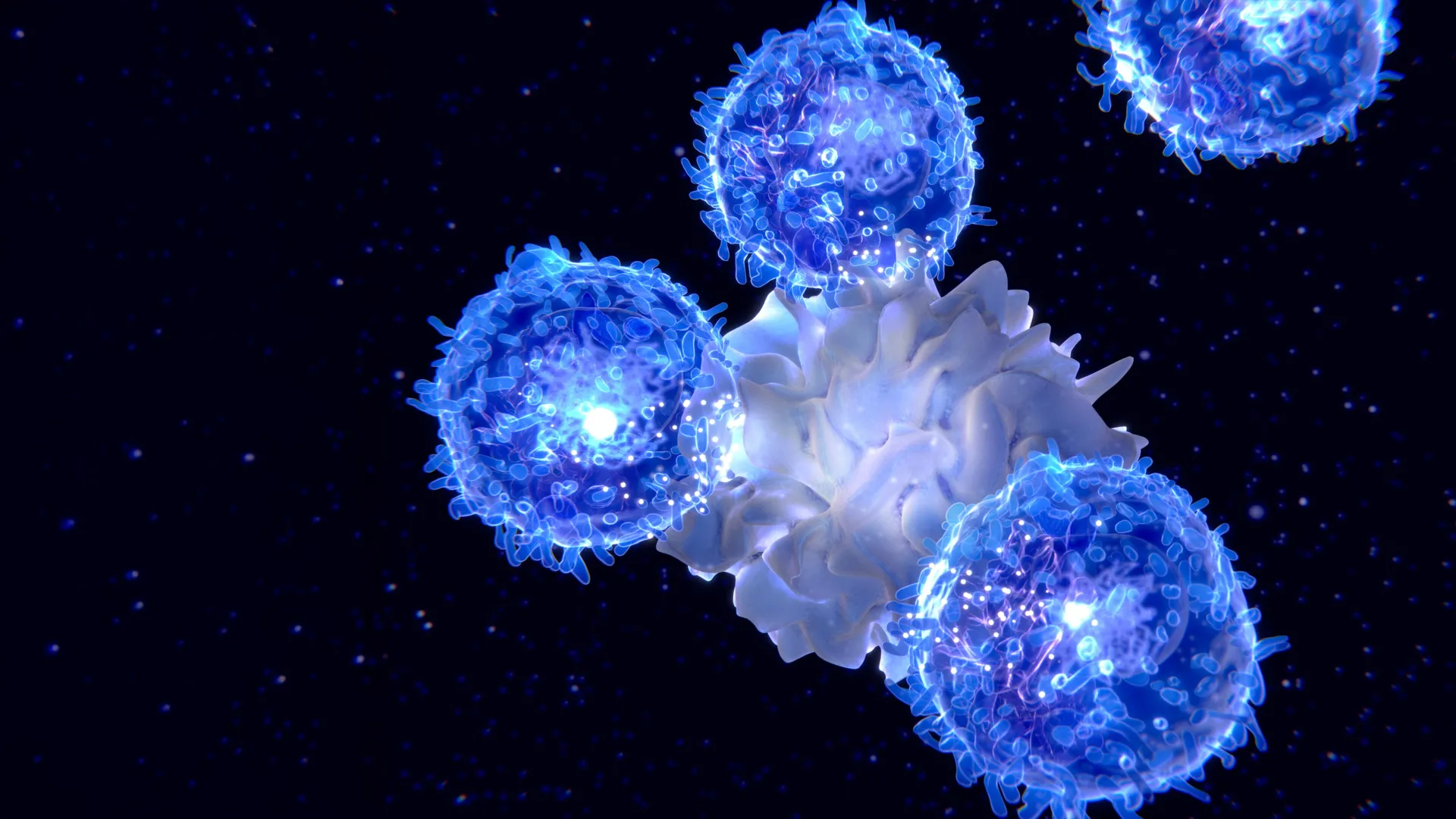

As people get older, the immune system often becomes less effective. Populations of T cells shrink, and the remaining cells may respond more slowly to germs. That slowdown can leave older adults more vulnerable to many kinds of infections.

To address this age related decline, scientists from MIT and the Broad Institute developed a method to temporarily reprogram liver cells in a way that strengthens T cell performance. The goal is to make up for the reduced output of the thymus, the organ where T cells normally mature.

In the study, the team used mRNA to deliver three important factors that support T cell survival. With this approach, they were able to rejuvenate the immune systems of mice. Older mice that received the treatment produced larger and more varied T cell populations after vaccination, and they also showed improved responses to cancer immunotherapy.

The researchers say that if this strategy can be adapted for patients, it could help people stay healthier as they age.

“If we can restore something essential like the immune system, hopefully we can help people stay free of disease for a longer span of their life,” says Feng Zhang, the James and Patricia Poitras Professor of Neuroscience at MIT, who has joint appointments in the departments of Brain and Cognitive Sciences and Biological Engineering.

Zhang is also an investigator at the McGovern Institute for Brain Research at MIT, a core institute member at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, and an investigator in the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. He is the senior author of the new study. Former MIT postdoc Mirco Friedrich is the lead author of the paper, which was published in Nature.

The Thymus and Why T Cells Decline With Age

The thymus is a small organ located in front of the heart, and it is essential for building a healthy supply of T cells. Inside the thymus, immature T cells go through a checkpoint process that helps create a diverse set of T cells. The thymus also releases cytokines and growth factors that help T cells survive.

But beginning in early adulthood, the thymus starts to shrink. This process is called thymic involution, and it reduces the body’s ability to produce new T cells. By about age 75, the thymus is essentially nonfunctional.

“As we get older, the immune system begins to decline. We wanted to think about how can we maintain this kind of immune protection for a longer period of time, and that’s what led us to think about what we can do to boost immunity,” Friedrich says.

Earlier efforts to rejuvenate the immune system have often focused on sending T cell growth factors through the bloodstream, but that approach can cause harmful side effects. Other researchers are investigating whether transplanted stem cells could help regrow functional thymus tissue.

A Temporary Liver Factory Powered by mRNA

The MIT team chose a different strategy. They asked whether the body could be prompted to create a temporary “factory” that produces the same T cell stimulating signals typically made by the thymus.

“Our approach is more of a synthetic approach,” Zhang says. “We’re engineering the body to mimic thymic factor secretion.”

They selected the liver for the job for several reasons. The liver can produce large amounts of protein even in old age. It is also easier to deliver mRNA to the liver than to many other organs. In addition, all circulating blood flows through the liver, including T cells, making it a practical place to release immune supporting signals into the bloodstream.

To build this factory, the researchers picked three immune cues involved in T cell maturation. They encoded these factors into mRNA and packaged the sequences into lipid nanoparticles. After injection into the bloodstream, the nanoparticles collect in the liver. Hepatocytes take up the mRNA and begin making the proteins encoded by it.

The three factors delivered were DLL1, FLT-3, and IL-7. These signals help immature progenitor T cells develop into fully differentiated T cells.

Vaccine and Cancer Immunotherapy Benefits in Older Mice

Experiments in mice showed multiple positive outcomes. In one test, the researchers injected the mRNA particles into 18 month old mice, roughly comparable to humans in their 50s. Because mRNA does not last long in the body, the team gave repeated doses over four weeks to keep the liver producing the factors consistently.

After the treatment, T cell populations increased substantially in both size and function.

The team then examined whether the approach improved vaccine responses. They vaccinated mice with ovalbumin, a protein found in egg whites that is often used to study immune reactions to a specific antigen. In 18 month old mice that received the mRNA treatment before vaccination, the number of cytotoxic T cells targeting ovalbumin doubled compared with untreated mice of the same age.

The researchers also found that the mRNA method could strengthen responses to cancer immunotherapy. They treated 18 month old mice with the mRNA, implanted tumors, and then gave the mice a checkpoint inhibitor drug. This drug targets PD-L1 and is intended to release the immune system’s brakes so T cells can attack tumor cells more effectively.

Mice that received both the checkpoint inhibitor and the mRNA treatment had much higher survival rates and lived longer than mice that received the checkpoint inhibitor drug without the mRNA treatment.

The researchers determined that all three factors were required for the immune improvement. No single factor could reproduce the full effect. Next, the team plans to test the approach in additional animal models and search for other signaling factors that might further strengthen immune function. They also want to investigate how the treatment influences other immune cells, including B cells.

Other authors of the paper include Julie Pham, Jiakun Tian, Hongyu Chen, Jiahao Huang, Niklas Kehl, Sophia Liu, Blake Lash, Fei Chen, Xiao Wang, and Rhiannon Macrae.

The research was funded in part by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the K. Lisa Yang Brain-Body Center at MIT, Broad Institute Programmable Therapeutics Gift Donors, the Pershing Square Foundation, the Phillips family, J. and P. Poitras, and an EMBO Postdoctoral Fellowship.