War-torn Myanmar voting in widely criticised ‘sham’ election

Kelly Ngand BBC Burmese,Mandalay EPA Myanmar’s military is holding a phased election over the next month Myanmar is voting

Kelly Ngand

BBC Burmese,Mandalay

EPA

EPAMyanmar is voting in an election widely dismissed as a sham, with major political parties dissolved, many of their leaders jailed and as much as half the country not expected to vote because of an ongoing civil war.

The military government is holding a phased ballot nearly five years after it seized power in a coup, which sparked widespread opposition and spiralled into a civil war.

Observers say the junta, with China’s support, is seeking to legitimise and entrench its power as it seeks a way out of the devastating stalemate.

More than 200 people have been charged for disrupting or opposing the polls under a new law which carries severe punishments, including the death penalty.

Polling began on Sunday and there were reports of explosions and airstrikes across multiple regions in the country as voting took place.

Three people were taken to hospital following a rocket attack on an uninhabited house in the Mandalay region in the early hours of Sunday, the chief minister of the region confirmed to the BBC. One of those people is in a serious condition.

Separately, more than ten houses were damaged in the Myawaddy township, near the border with Thailand, following a series of explosions late on Saturday.

A local resident told the BBC that a child was killed in the attack, and three people were taken to hospital in an emergency condition.

Further reports of casualties have emerged following other explosions.

Voters have told the BBC that the election feels more “disciplined and systematic” than those previously.

“The experience of voting has changed a lot,” said Ma Su ZarChi, who lives in the Mandalay region.

“Before I voted, I was afraid. Now that I have voted, I feel relieved. I cast my ballot as someone who has tried their best for the country.”

First-time voter Ei Pyay Phyo Maung, 22, told the BBC she was casting her ballot because she believed that voting is “the responsibility of every citizen”.

“My hope is for the lower classes – right now, the prices of goods are skyrocketing, and I want to support someone who can bring them down for those struggling the most,” she said.

“I want a president who provides equally for all people.”

The Burmese junta has rejected criticism of the polls, maintaining that it aims to “return [the country] to a multi-party democratic system”.

After casting his vote at a highly fortified polling station in the capital, junta chief Min Aung Hlaing told the BBC that the election would be free and fair.

“I am the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces, a civil servant. I can’t just say that I want to be president,” he said, stressing that there are three phases of the election.

Earlier this week, he warned that those who refuse to vote are rejecting “progress toward democracy”.

Win Kyaw Thu/BBC

Win Kyaw Thu/BBCFilm director Mike Tee, actor Kyaw Win Htut and comedian Ohn Daing were among the prominent figures convicted under the law against disrupting polls, which was enacted in July.

They were each handed a seven-year jail term after criticising a film promoting the elections, state media reported.

“There are no conditions for the exercise of the rights of freedom of expression, association or peaceful assembly,” the United Nations’ top human rights official Volker Türk said.

Civilians are “being coerced from all sides”, Mr Türk said in a statement on Tuesday, noting that armed rebel groups have issued their own threats asking people to boycott the polls.

The military has been fighting on several fronts, against both armed resistance groups who oppose the coup, as well as ethnic armies which have their own militias. It lost control of large parts of the country in a series of major setbacks, but clawed back territory this year following relentless airstrikes enabled by support from China and Russia.

The civil war has killed thousands of people, displaced millions more, destroyed the economy and left a humanitarian vacuum. A devastating earthquake in March and international funding cuts have made the situation far worse.

All of this and the fact that large parts of the country are still under opposition control presents a huge logistical challenge for holding an election.

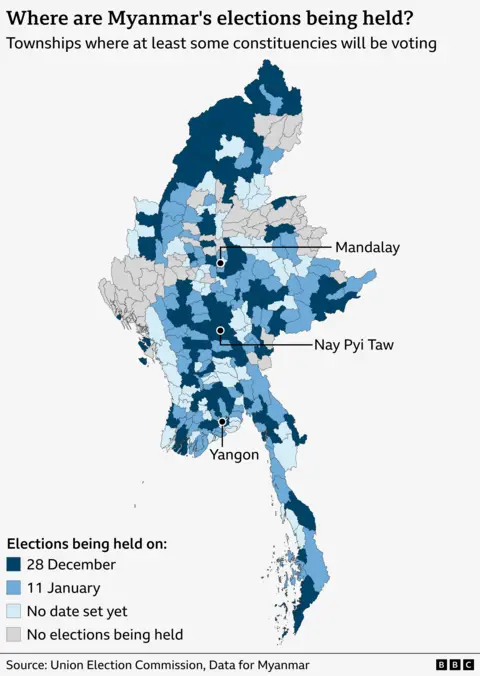

Voting is set to take place in three phases over the next month in 265 of the country’s 330 townships, with the rest deemed too unstable. Results are expected around the end of January.

There is not expected to be any voting in as much as one half of the country. Even in the townships that are voting, not all constituencies will go to the polls, making it difficult to forecast a possible turnout.

Six parties, including the military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party, are fielding candidates nationwide, while another 51 parties and independent candidates will contest only at the state or regional levels.

Some 40 parties, including Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League of Democracy, which scored landslide victories in 2015 and 2020, have been banned. Suu Kyi and many of the party’s key leaders have been jailed under charges widely condemned as politically motivated, while others are in exile.

“By splitting the vote into phases, the authorities can adjust tactics if the results in the first phase do not go their way,” Htin Kyaw Aye, a spokesman of the election-monitoring group Spring Sprouts told the Myanmar Now news agency.

Ral Uk Thang, a resident in the western Chin state, believes civilians “don’t want the election”.

“The military does not know how to govern our country. They only work for the benefit of their high-ranking leaders.

“When Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s party was in power, we experienced a bit of democracy. But now all we do is cry and shed tears,” the 80-year-old told the BBC.

Western governments, including the United Kingdom and the European Parliament, have dismissed the vote as a sham, while regional bloc Asean has called for political dialogue to precede any election.