A rare cancer-fighting plant compound has finally been decoded

Researchers at UBC Okanagan have figured out how plants make mitraphylline, a rare natural substance that has drawn attention

Researchers at UBC Okanagan have figured out how plants make mitraphylline, a rare natural substance that has drawn attention for its potential role in fighting cancer.

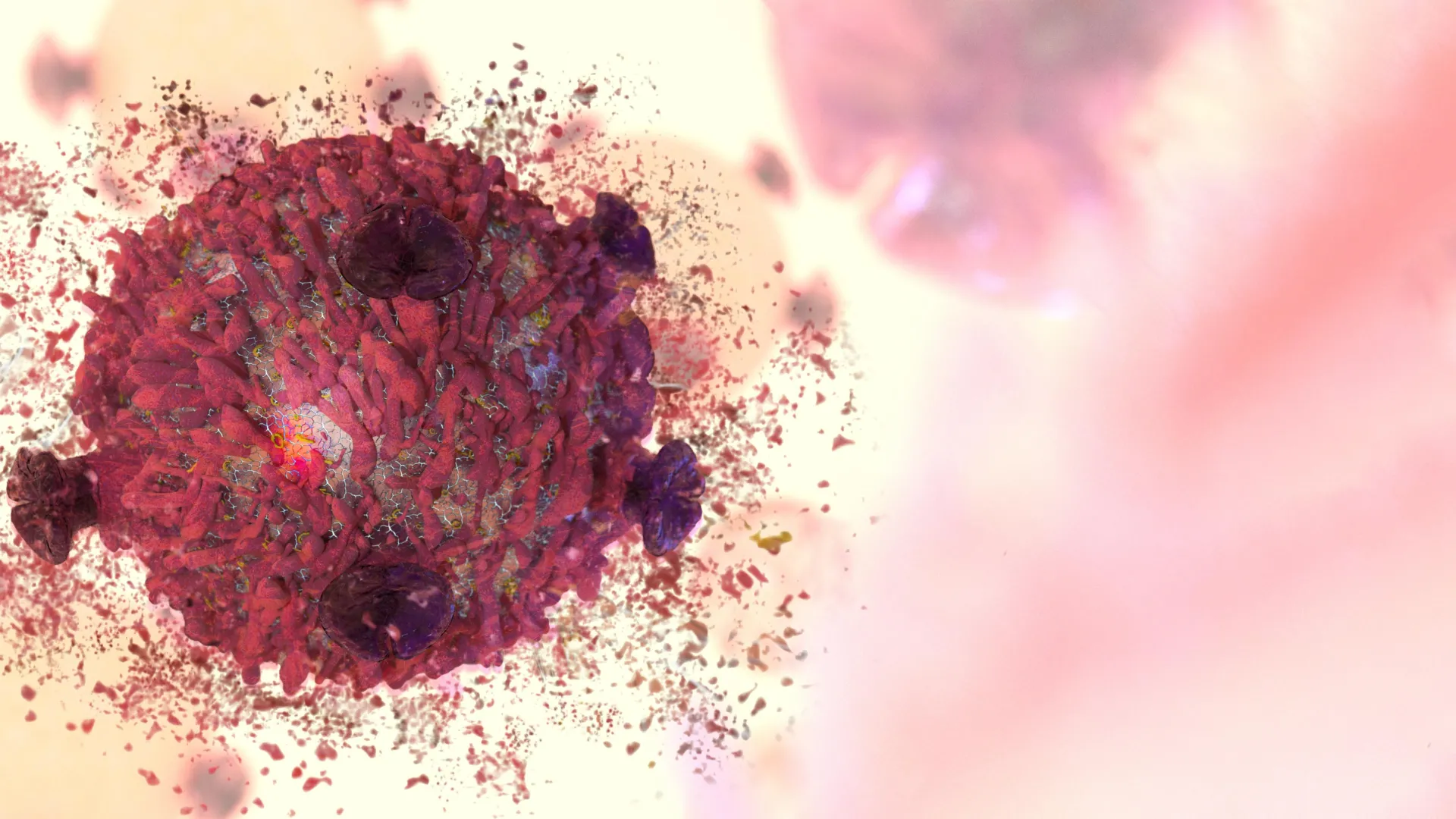

Mitraphylline is part of a small and unusual family of plant chemicals known as spirooxindole alkaloids. These molecules are defined by their distinctive twisted ring shapes, which help give them powerful biological effects, including anti tumor and anti inflammatory activity.

For years, scientists knew these compounds were valuable but had little understanding of how plants actually assembled them at the molecular level.

Solving a Long Standing Biological Mystery

Progress came in 2023, when a research team led by Dr. Thu-Thuy Dang in UBC Okanagan’s Irving K. Barber Faculty of Science identified the first known plant enzyme capable of creating the signature spiro shape found in these molecules.

Building on that discovery, doctoral student Tuan-Anh Nguyen led new work to pinpoint two key enzymes involved in making mitraphylline — one enzyme that arranges the molecule into the correct three dimensional structure, and another that twists it into its final form.

“This is similar to finding the missing links in an assembly line,” says Dr. Dang, UBC Okanagan Principal’s Research Chair in Natural Products Biotechnology. “It answers a long-standing question about how nature builds these complex molecules and gives us a new way to replicate that process.”

Why Mitraphylline Is So Hard to Obtain

Many promising natural compounds exist only in extremely small quantities within plants, making them expensive or impractical to produce using traditional laboratory methods. Mitraphylline is a prime example. It appears only in trace amounts in tropical trees such as Mitragyna (kratom) and Uncaria (cat’s claw), both of which belong to the coffee plant family.

By identifying the enzymes that construct and shape mitraphylline, scientists now have a clear guide for recreating this process in more sustainable and scalable ways.

Toward Greener Drug Production

“With this discovery, we have a green chemistry approach to accessing compounds with enormous pharmaceutical value,” says Nguyen. “This is a result of UBC Okanagan’s research environment, where students and faculty work closely to solve problems with global reach.”

Nguyen also emphasized the personal impact of the work. “Being part of the team that uncovered the enzymes behind spirooxindole compounds has been amazing,” he says. “UBC Okanagan’s mentorship and support made this possible, and I’m excited to keep growing as a researcher here in Canada.”

Global Collaboration and Future Directions

The project was a collaborative effort between Dr. Dang’s laboratory at UBC Okanagan and Dr. Satya Nadakuduti’s team at the University of Florida.

Funding came from several sources, including Canada’s Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council’s Alliance International Collaboration program, the Canada Foundation for Innovation, and the Michael Smith Health Research BC Scholar Program. Additional support was provided by the United States Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

“We are proud of this discovery coming from UBC Okanagan. Plants are fantastic natural chemists,” Dr. Dang says. “Our next steps will focus on adapting their molecular tools to create a wider range of therapeutic compounds.”