Bill Bryson on why he has updated A Short History of Nearly Everything

Bill Bryson David Levene/eyevine Rowan Hooper: Bill, when I mentioned in the office that you were coming in, people

Bill Bryson

David Levene/eyevine

Rowan Hooper: Bill, when I mentioned in the office that you were coming in, people reacted like I’d said Ryan Gosling or David Beckham was visiting.

Bill Bryson: It’s my looks.

RH: Your 2003 book, A Short History of Nearly Everything, became one of the best-selling non-fiction books of the 21st century. And now you’ve revised it.

It was over 20 years old. And, obviously, science has moved on a great deal. Take the Denisovans. When I wrote the book, nobody had a clue about these archaic peoples. Same with Homo floresiensis, the hobbit. So I thought I’d bring it up to date. It became a real pleasure for me because I got to go back and reinterview a lot of the people that I spoke to first time around.

RH: It’s one of the joys of being a science reporter, isn’t it? The time that scientists give you, the privilege of getting the time of world experts.

I think for a lot of scientists, nobody’s ever really expressed much interest in what they do. And the more technical the work, the less likely that people in a pub are gonna say: “Oh, tell me more.” But here am I saying: “This is amazing. Tell me all about it.”

And the question I always ask them was: what got you started in that field, what was the magic moment that made you want to spend your life studying lichens or whatever?

RH: Let me turn that question on you: what was the magic moment for you and science?

I was terrible at science at school. Bored out of my mind. There was a tendency when I was a kid growing up in America in the 50s and 60s that when they taught you physics, it was to make you into a physicist, or if they taught you chemistry, it was like they were trying to create new generations of chemists.

And there’s loads of people like me that are never going to be scientists, but ought to be able to engage with science at some level. Obviously, science explains everything there is to know. It tells us who we are, where we’re going and what we have to do if we want to get there. I thought there’s got to be some level at which I can engage with science and marvel at the wonder of it without having to go into lots of equations and all that sort of blackboard-type stuff.

And I put this to my publishers and they all said, “No, that’s just a really dumb idea, you’re not qualified, you just shouldn’t be doing this. Leave that to Stephen Hawking.” But they let me do it.

And, luckily, it turned out that there are lots of people like me in the world who want to know about science. The whole idea of the book was: how do we know what we know? How do scientists figure these things out?

One of the things that I hadn’t expected was that the amount of things we don’t know is actually exciting. It would be awful if we knew everything.

You know, there is a lot we could do with knowing, just the very fact that we don’t know how many insect species there are on Earth.

RH: They’re going extinct before we even know how many there are. That leads me to climate change, which isn’t in the book, and I wondered why you decided to leave that out?

Yeah, it was a tough call, but the idea of the book is really to try to understand how we got to where we are now, our current state of knowledge in so far as I’m capable of understanding it. So the book is a lot about the history of science.

Penny Sarchet: One thing that’s changed between the original and the new version is that, in 2003, a long human life lasted about 650,000 hours or 74.2 years, but now it’s 700,000 hours, 80-odd years. That’s quite a boost in longevity over that time.

The point I was making originally was that we only live for 650,000 hours. If you think about the number of hours of your life you’ve wasted, fooled around doing idle things, just watching Coronation Street.

PS: Was there anything that stood out when you were revising the book that was an unexpected delight?

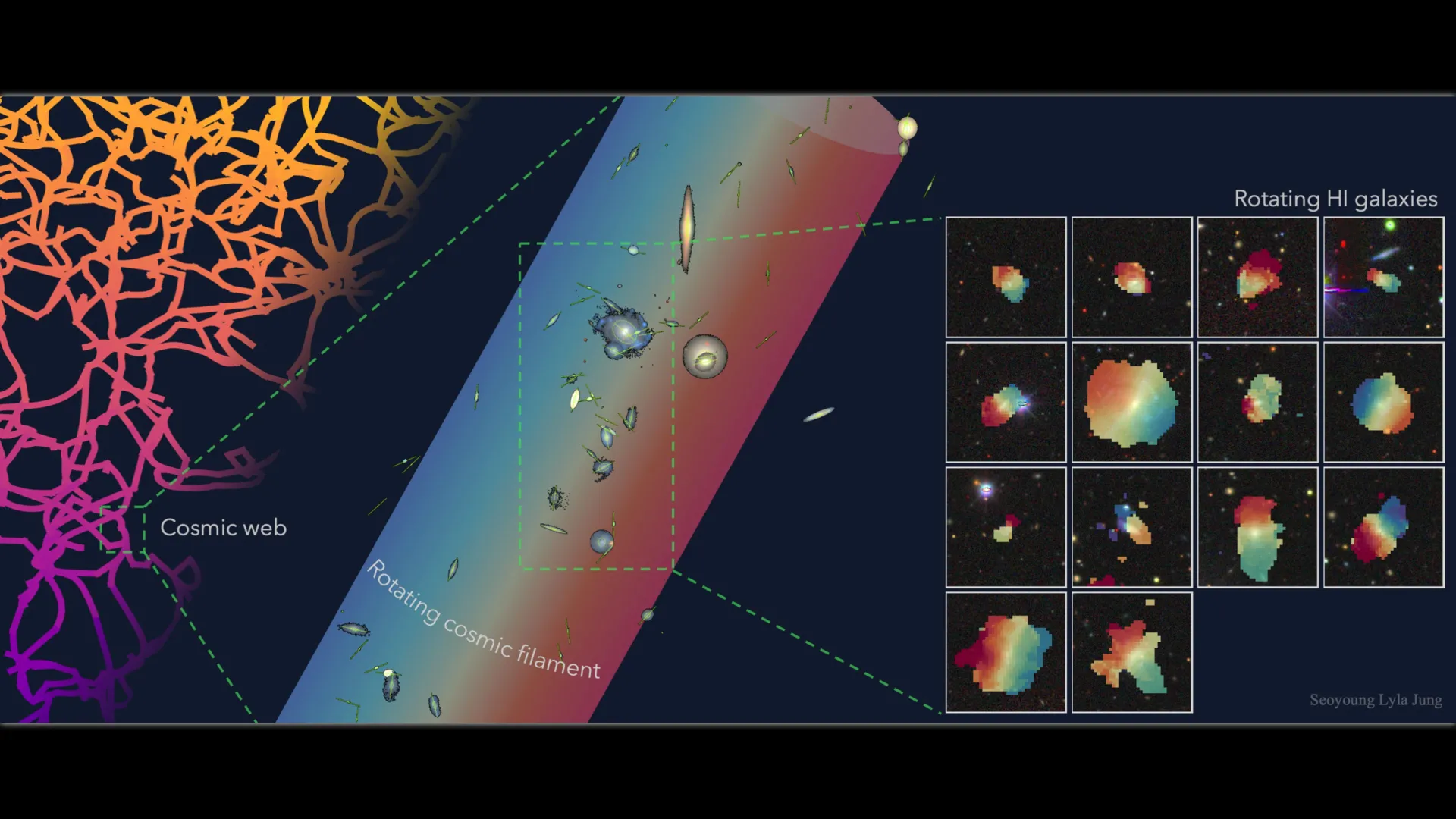

The one that rocked me on my heels was discovering that there are twice as many known moons in the solar system. I thought, “How hard is it to identify a moon? Where were they all?”

“

One of the things that I hadn’t expected was that the amount of things we don’t know is actually exciting

“

The number of moons of Jupiter has trebled in 20 years. Of course, a lot of these moons are very small. And, apparently, the definition of a moon is anything rocky that orbits a planet.

RH: Another thing that is very different is the proliferation of the human family tree – it’s more like a hedge! Did that surprise you? It was starting to look quite straightforward, wasn’t it?

Yeah, it was. Not just to me, but I think to people in the field. They were pretty confident that they had kind of figured things out. And then, the Denisovans, also the hobbits of Flores. And other archaic human groups that have been found since then.

The thing that fascinates me as a complete outsider is, how did these people all get around? I mean, how did they disperse and what happened when they came upon each other? There’s a tendency to think there would have been fighting, but actually there was a lot of interbreeding. I think it’s kind of heartwarming, the idea that these people were living side by side for long periods. Because we modern Homo sapiens don’t do that very well at all.

Alec Luhn: Twenty years ago, there was a more benign kind of atmosphere. Now, in the US, people talk about a war on science. Was it daunting to do a 2.0 version of your book in the world in which we live?

The whole idea of the book is that, because [the first one has] been out there for 20 years, I’m hoping I’ve done it for another 20 years. And I’m hoping, with this current US administration, we will look back on it some years from now and just see it as a kind of a blip.

It would just be tragic if those sorts of policies and that kind of vindictiveness and institutionalised anger became a permanent feature of the US.

This is an edited version of an interview broadcast on New Scientist’s podcast The world, the universe and us

Topics: