Alpine communities face uncertain future after 2025 glacier collapse

Blatten in Switzerland was buried by a landslide in May 2025 ALEXANDRE AGRUSTI/AFP via Getty Images In May, the

Blatten in Switzerland was buried by a landslide in May 2025

ALEXANDRE AGRUSTI/AFP via Getty Images

In May, the village of Blatten in the Swiss Alps was destroyed when a huge chunk of a glacier collapsed, but thanks to careful monitoring, almost all of its residents were saved.

The first sign of an impending disaster appeared on 14 May, when an official observer for Switzerland’s snow avalanche warning service reported a small rockfall above the village. These observers have other full-time jobs in the area, but are trained to keep an eye on the slopes.

The service then took a look at images from a camera installed on the glacier above the village after snow avalanches in the 1990s. “In those photos, they could see changes on the ridge on the mountain,” says Mylène Jacquemart at ETH Zurich in Switzerland. “It just so happened that the camera was looking at it from a very useful angle.”

That led to further investigations, which found that a major landslide was likely. On 18 and 19 May, 300 people were evacuated from the village, with just one 64-year-old man refusing to leave.

On 28 May, a large part of the mountain above the glacier collapsed. “This is a really, really large rock avalanche on its own,” says Jacquemart.

The glacier was already covered in a large amount of rubble from smaller rockfalls over the preceding months and years. When the rockfall hit it, the entire lower part gave way, resulting in 3 million cubic metres of ice and 6 million cubic metres of rock plunging into the valley and destroying most of the village. The man who refused to leave was killed.

Many stories in the media have suggested there was some kind of high-tech monitoring of the glacier going on, says Jacquemart, but that isn’t the case. “There was not some fancy alarm system, you know, in someone’s office, a little red light [that] started blinking, saying, hey, there’s an issue there.”

But what Switzerland’s system does have is clear lines of communication and responsibility, she says. From the observers onwards, people know who to talk to and who makes the decision on whether to evacuate or not.

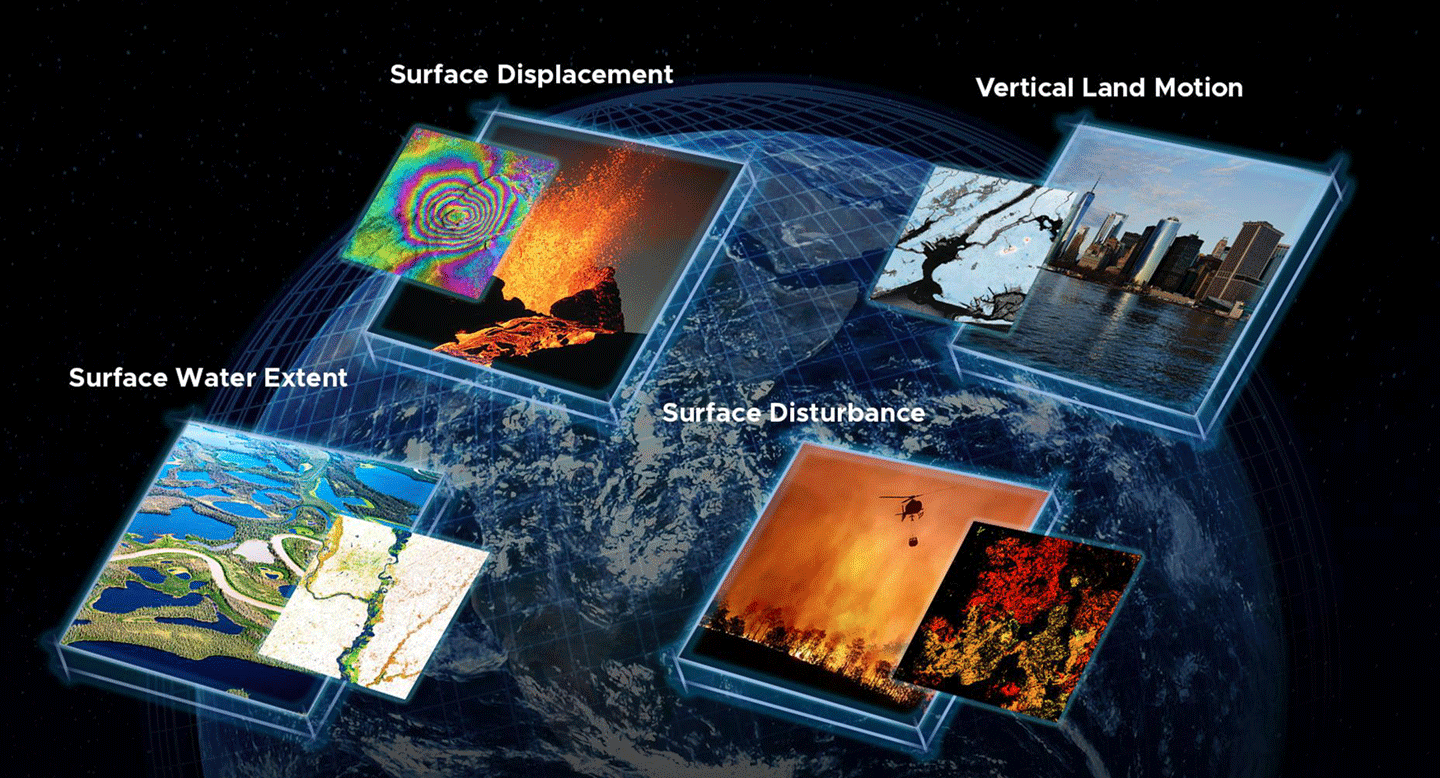

Satellite image from 30 May showing the extent of the area affected by the landslide

European Union, Copernicus Sentinel-2 imagery

So what caused this disaster? The risk of ice falls has been diminishing as Alpine glaciers shrink, but there is no doubt that global warming is increasing the frequency of rockfalls. The upper parts of the mountains are usually permanently frozen, with ice sealing any cracks or crevices.

As these regions warm – Switzerland is now nearly 3°C warmer than it was in pre-industrial times, on average – this permafrost is sometimes thawing, while water is often falling as rain rather than snow. This means cracks can become filled with liquid water that expands as it freezes, forcing rocks apart.

“We see a pretty close connection with climate change and rock failures, or rockfall,” says Jacquemart. “There are dramatic changes going on in high mountains and those are, as far as I can tell, all bad.”

But she is cautious about blaming recent warming for events on a scale as vast as the Blatten disaster. It is possible that the ultimate cause is the warming since the last glacial period ended around 10,000 years ago, she says. “Maybe this is a slope that’s adjusting to its ice-free conditions, compared to the last ice age, and this adjustment is really slow, and eventually it leads to failure.”

What happens next for the residents of Blatten isn’t clear either. The village can’t be rebuilt on the unstable debris – a mix of rock and ice – but local authorities have already announced plans to rebuild nearby. However, this area is also at risk from landslides and building protective structures is extremely expensive.

“Mountain communities around the world, from the Alps to the Andes and the Himalayas, are threatened by increasing intensity and frequency of mountain-related hazards,” Kamal Kishore, head of the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, said in a statement after the disaster. “Their lives, ways of life, culture, and heritage are all threatened.”

Topics: