Quantum computers turned out to be more useful than expected in 2025

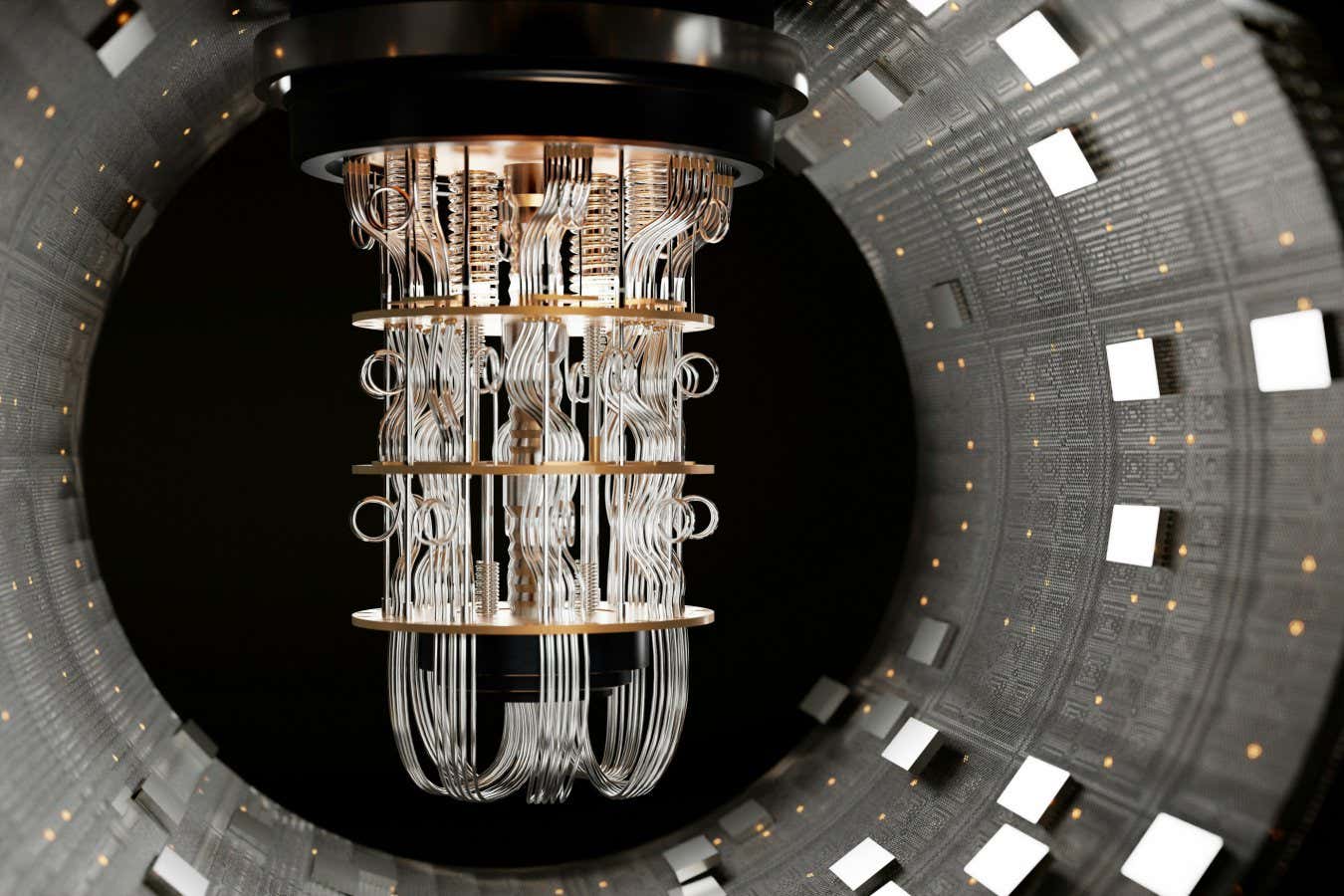

Quantum computers could help us understand how quantum objects behave Galina Nelyubova/Unsplash For the past year, I kept bringing

Quantum computers could help us understand how quantum objects behave

Galina Nelyubova/Unsplash

For the past year, I kept bringing the same story to my editor: quantum computers are on the edge of becoming useful for scientific discovery.

Of course, that has always been the goal. The idea of using quantum computers to better understand our universe is part of their origin story, and it even featured in a 1981 speech by Richard Feynman. Contemplating the best way to simulate nature, he wrote: “We can give up on our rule about what the computer was, we can say: Let the computer itself be built of quantum mechanical elements which obey quantum mechanical laws.”

Today, Feynman’s vision has been realised by Google, IBM and dozens more companies and academic teams. Their devices are now being used to simulate reality at the quantum level – and here are some highlights.

For me, this year’s quantum developments started with two studies that landed on my desk in June, dealing with high-energy particle physics. Two separate research teams had used two very different quantum computers to simulate the behaviours of pairs of particles in quantum fields. One used Google’s Sycamore chip, made from tiny superconducting circuits controlled with microwaves, and the other used a chip produced by quantum computing company QuEra, based on extremely cold atoms controlled with lasers and electromagnetic forces.

Quantum fields encode how a force, such as the electromagnetic force, would act on a particle at any position in the universe. They also have local structure that dictates the behaviours you should see if you zoom in on any particle. Such fields are hard to simulate in the case of particle dynamics – when the particle is doing something over time and you want to make something like a movie of it. For two very simplified versions of quantum fields that show up in the standard model of particle physics, the two quantum computers tackled this exact task.

Jad Halimeh at the University of Munich, who works in the field but hadn’t been involved with either experiment, even told me that a more muscular version of these experiments, simulating more complex fields on larger quantum computers, could eventually help us understand what particles do inside particle colliders.

Three months later, I was on the phone with two other teams of researchers, again discussing those same two types of quantum computers, which had now been put in service of condensed matter physics. Condensed matter physics is dear to my heart because I studied it in graduate school, but its impact extends far beyond this columnist’s proclivities. It has been particularly critical for the development of the semiconductor technologies that underlie everyday devices such as smart phones.

In September, researchers at Harvard University and the Technical University of Munich in Germany used quantum computers to simulate two exotic phases of matter that had been predicted in theory but eluded more traditional experiments. The quantum computers proved adept at predicting the properties of these strange materials, something that growing and probing crystals in the lab has so far failed to accomplish.

October brought the prospect of a practical use for a new superconducting quantum computer from Google, called Willow. The firm’s researchers and their colleagues used Willow to run an algorithm that can be used to interpret data from nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, which is a commonly used technique for studying molecules in biochemical research.

Though the team’s demonstration with real NMR data didn’t do anything that a traditional computer could not, the mathematics of the algorithm promises to one day exceed the capabilities of classical machines, allowing researchers to learn unprecedented details about molecules. How quickly this bears out depends on the pace at which quantum computing hardware improves.

A month later, a third kind of quantum computer entered the conversation. A company called Quantinuum showed that their Helios-1 quantum computer made from trapped ions can run simulations of a mathematical model for perfect electrical conductivity, or superconductivity. Because they conduct electricity without any losses, superconductors may open the door for extremely efficient electronics or even make the electrical grid more sustainable. However, all known superconductors work only under high pressure or extremely low temperature, which makes them impractical. A mathematical model that reveals exactly why some materials superconduct would be a crucial stepping stone towards building useful superconductors.

Helios-1 simulated what Henrik Dryer, a researcher at Quantinuum, told me is possibly the most important such model; one that has held physicists’ attention since the 1960s. And while this specific simulation didn’t offer any radical new insight into superconductivity, it did announce quantum computers as valuable players in physicists’ long-running quest to understand them better.

Just a week later, I found myself on a call with Sabrina Maniscalco from the quantum algorithms firm Algorithmiq, discussing metamaterials. These are materials whose microscopic details can be engineered to have special properties that naturally occurring materials don’t have. They can also be tailor-made for some specific purposes, from rudimentary invisibility cloaks to chemical ingredients that can accelerate reactions.

Metamaterials are also something that I had dabbled in as a graduate student, and Maniscalco’s team worked out how to simulate one using an IBM quantum computer made from superconducting circuits. Specifically, they could track how a metamaterial scrambles information, including in regimes where a more conventional computer may struggle. Though this may sound like a rather abstract setup, Maniscalco told me that it could advance research into chemical catalysts as well as solid state batteries and certain devices that convert light to electricity.

As if particle physics, novel phases of matter, molecular investigations, superconductors and metamaterials weren’t enough, while I was outlining this column I got a tip about a study where a team of researchers at the University of Maryland in the US and the University of Waterloo, Canada, used a trapped ion quantum computer to determine how particles bound by the strong nuclear force behave at different temperatures and densities. Some of this behaviour is thought to take place inside neutron stars, which are poorly understood cosmic objects, and also to have occurred in the early universe.

While the team’s quantum calculation involved approximations that don’t quite match the most realistic models of the strong force, the study makes the case for yet another field of physics where quantum computers are up-and-coming as discovery machines.

Certainly, this abundance of examples also comes with an abundance of caveats and question marks. Most mathematical models that have been simulated on quantum hardware require some number of simplifications and approximations compared with the most realistic ones, most quantum computers are still so error-prone as to require the results of their computations to be post-processed to mitigate or remove those errors, and the issue of benchmarking quantum computers’ results against what the best conventional computers can do remains thorny.

Put simply, traditional computing and simulation methods are another area where progress has been fast and encouraging, placing classical and quantum computer researchers into a dynamic back-and-forth where yesterday’s most complex or fastest computation inevitably becomes tomorrow’s runner-up. In the past month, IBM even partnered with several other companies to launch a publicly available “quantum advantage tracker”, which will eventually become a leaderboard showing where quantum computers are pulling ahead of their conventional counterparts – or not.

But even if quantum computers don’t make it to the top of that list any time soon, this past year of reporting still shifted my priors towards excitement and anticipation. That’s because these experiments effectively move quantum computers from being the subject of scientific study to being tools for doing science in a way that was impossible just a few years ago.

At the start of this year, I expected to be mostly writing about benchmarking experiments, where quantum computers run protocols that show off their quantumness rather than solve any useful problems. Such computations often serve to highlight just how different quantum computers are from conventional computers, and they can underline their potential to do radically new things. But the road from there to a useful calculation for a working physicist seemed long and not at all obvious. Now, albeit with caution, I think that road may be shorter than I expected. I’m sure more quantum surprises will await me in 2026.

Topics: